On being a resisting spirit, basically

This is the first summer in many years I’m not working on the book, because the book is done! (yes, I have #ohmygodwhyisthisbooknotdoneyet AND #ohmygodthebookisdone hashtags on Instagram). Resisting Spirits: Drama Reform & Cultural Transformation in the People’s Republic of China will be out this August with the University of Michigan Press (the paperback is a very reasonable $24.95!). I’m very pleased with the end product, but it has been a very, very painful process. I’ve been pretty transparent on my social media about the misery, anxiety & depression I’ve dealt with over the past couple of years, a lot largely related to the monograph, so I figured a retrospective & and some thoughts on the whole publishing process & would be good to write through, and may even prove useful for others. So: a bit of a timeline, some thoughts on editing & collegiality, revising, and other motley bits.

Timeline

One of the first things senior colleagues tell you when you arrive at a university (at least in my experience) is “don’t worry about the book right away!” This is, on the one hand, totally sensible advice: in my case, I defended my dissertation on July 29th, 2013, and literally two weeks later became an assistant professor. I needed time away from the dissertation! Unfortunately, we don’t have time, because not every publishing process is smooth & even if you have a good piece of scholarship. I die a little inside every time I hear a colleague say something along the lines of “publishing a book is easy” (and yes, I’ve heard this several times over the years & not directed at me, but it certainly felt like it when I was really struggling). Sometimes it is. Often times it isn’t. The number of senior scholars who came crawling out of the woodwork to say “Let me tell you about my publishing horror story!” was absolutely staggering (my response was always “let’s do this after we’ve hit the point where my publishing horror story is no longer a horror story”).

In my case, I asked my advisors for advice on presses to submit to, and had one series that was highlighted & “I think this would be a perfect fit!” I met with the acquisitions editor briefly at AAS in 2016, after sending my prospectus to them & one of the editors of the series I was interested in. I spent the summer revising, sent the mss off at the end of the summer, and then a couple of months later, got a response that was pretty shattering for me & they didn’t really want it, but would give me the opportunity to revise and submit it again for consideration. The responses from the series editors ranged from one completely effusive “love it” to varying degrees of “meh.” It was not, to say the least, very encouraging (despite the fact that the one “love it” response was something I held on to, even when I was struggling mightily with what to do); I had never had anything less than an “accept pending very minor revisions” for an article, so to have someone say they found my book boring, esoteric & ultimately derivative and pretty pointless (in a slightly nicer way) was alarming. Was the book that bad?

Well, in retrospect, yes, it was (it’s come a very long way since then). But it was bad in the way that a lot of dissertations-turned-into-book-drafts are bad. On the one hand, you’ve spent so much time with the damn thing that you can have trouble seeing the forest for the trees (and also have trouble imagining it as something else); on the other, a monograph is not a dissertation. What it needed was reconceptualizing, and that can be very hard to do when you have this complete thing — the dissertation — that now needs to be turned into a different kind of complete thing. I didn’t have a lot of opportunities to have outside eyes on the work (more on that later), which I desperately needed in the revision process. We all need that in the revision process & preferably from people who have overseen the process of dissertation-to-book before.

In any case, I was really uneasy about revising for this series, since it wasn’t like they were offering an advance contract or anything, but I didn’t know what else to do — I looked through presses I liked, and didn’t see any series that leapt out at me as being a perfect fit. I talked to friends who had published with various presses, and asked colleagues what to do. Do you just spam acquisitions editors with your prospectus? I had no clue. One senior colleague told me to stick with the noncommittal press, because at least my “foot was in the door, and that’s the hardest part to get over.” I kept fretting while I looked at this apparently lousy draft, tried to revise, and tried to figure out what to do.

At the annual AAS in 2017 (so one year after I met with acquisitions editor #1), one of my good friends from grad school finally said over breakfast “Look, you just need to find another press and stop wasting your time with Press #1. It’s not the right series for you or this book.” I knew they were right, since they knew my work & me, but -where next? Another grad school friend offered to take me to meet their acquisitions editor at Stanford, but I had a hard time imagining my kind of work with SUP. Luckily, I happened to be on a panel that year with Tarryn Chun, who was then a post-doc at University of Michigan. She’s a theatre historian & literary scholar, and I figured she might have some ideas on a good press for my particular brand of highly interdisciplinary, neither-fish-nor-fowl scholarship. I was starting to really feel the pressure of tenure coming up, and I needed a press & and I needed one fast.

“Oh, you know, Tang Xiaobing has a new series he’s editing with Mary Gallagher. Why don’t you contact him?”

Of course I was familiar with Tang’s work, and as it happened, in the print edition of Cross-Currents my mahjong article came out in, he had published a piece on street theatre in the 1940s. But that series — “China Understandings Today” — was brand new and basically not advertised. You had to dig on the UM website to find it, and the only reason Tarryn knew about it was because she was actually at Michigan and working with them. When I did finally work up my nerve in early May (after revising my prospectus again), the listed email didn’t even work (luckily, someone in the China center got back to me right away & told me to just contact Tang directly, which I did).

He liked the prospectus. He asked to see two sample chapters, found one of them (the very oldest part of the dissertation — more on that later) very conventional and not terribly interesting, but quite liked the other one. After some consultation with his co-editor, he sent me an email saying they wanted to put the book under advance contract and schedule a workshop for the fall (I was actually running a friend from grad school through a dungeon in Final Fantasy XIV when I got this email, and squealed so loud in voice chat I think he thought something was terribly wrong — no, just a wave of elation!). A workshop! I thought. Paid for by the press & UM’s Lieberthal-Rogel Center for Chinese Studies! They were going to fly me to Ann Arbor, put me up for two nights, bring in another senior scholar to comment on the book, and spend an entire morning

discussing my book. I was amazed. This seemed so -humane! Recognizing that it’s not a simple “go from point A to B” when it comes to revising a dissertation! They were offering me help

in doing that.

My workshop took place in early October, and they brought in Judith Zeitlin from Chicago via Skype (who of course has written the book on ghost opera in the imperial period). Tang Xiaobing was there, as well as junior scholars SE Kile & Emily Wilcox. They’d all read my book! I hadn’t had this many eyes on the thing -ever. It felt a bit like being in coursework again, when we’d have the entire seminar picking apart our drafts. It was wonderful. And so very important for revisions. Even some of the most minor comments that day — off-handed remarks, really — became major things that helped make the book into what it is today.

I spent the next 4 months furiously revising. My stress levels at this point were incredibly high & had been for a long time, and they kept rising. But I had my advance contract, they liked the book, they wanted the book, and I now had generous feedback to work with. I finished revisions in mid-February, sent it off, and then waited.

And waited.

And waited.

The outside reviews should’ve been back in early summer, but I spent 95% of the summer of 2018 having hysterical sobbing jags, panic attacks, and anxiety so bad I spent a lot of time just laying on my living room floor staring at the ceiling. I developed this wonderful tic where it felt like things were crawling all over me, even when I knew there was nothing on me. The high point of my anxiety was a few weeks before the reviews finally came back (in August), when I had a pretty severe panic attack and the things-are-crawling-all-over-me tic combined. I didn’t think I was going to die, but I did think I was quite possibly careening towards a complete mental breakdown & hospitalization of some sort, and I don’t say that lightly. A colleague (two, actually) told me that if that ever happened again, I was to call them and they’d drive me to the hospital.

Luckily, the reviews came back in August & they were good. One was absolutely glowing; the other read as pretty neutral & both with a lot of good feedback. The glowing one cast the “neutral” one in a more positive light, I think, so I’m grateful for Reviewer A, whoever they were. Yes, the press said, they could get the book out by the time my tenure file needs to be submitted (October 2019). And true to their word, UM Press has been blindingly fast in the production phase — I submitted revisions on November 1, had extensive copy edits back in early January, had page proofs back in April, and final page proofs done by the end of May. The book will be out in August — so, a little over 2 years since my first contact with Tang Xiaobing, and basically a year since I got the outside reviews back.

However, this required a rather fast turnaround on my part — a smidge over 2 months from the external reviews to me submitting my revisions — and I had a long list of things to fix. And by this point, I was so tired of the book, my sources, revising, I had no idea what to do next. How in the world was I going to get all this done in 2 months?

Enter Eric Schluessel, stage right.

On Editing, “Collegiality” & Professionalizing Relationships

My colleague Amanda Hendrix-Komoto & I were sitting at an ice cream shop in town in late July or early August, before the outside reviews were in. I was fretting about how I was going to turn revisions around, assuming the outside reviews ever came back in, for the book to come out in a timely manner & me to have some chance of getting tenure. Things were looking pretty dire. “You should hire an editor,” she said (yet again; she’d suggested this several times over the summer. I balked, not because I thought I didn’t need help, but the idea was totally foreign to me). She’d hired a well-known one in her field to help with her first book. I’d never heard of anyone (at least, among my friends) hiring an editor to work through drafts. Of course, I’d helped a colleague with his manuscript & essentially done editing work (I’d read the book enough to catch typos in languages I don’t even know that the copy editor missed, if that tells you anything), but isn’t that the kind of thing we’re “supposed” to do as colleagues? She talked about how the process was going to look with her editor. And pointed out that when you’re paying someone, that comes with a different kind of relationship than if you’re just dumping more unpaid labor on already overburdened friends and colleagues. But how do you find an editor? Do you google “Chinese history book editor”? Is this an actual service that people do? “What about Eric?” she finally said. A lightbulb went on in my head.

Eric is a dear friend, super-talented historian, great teacher, wonderful colleague (at the University of Montana), and & as it turns out — A++, top-notch, amazing editor that freelances when he’s not busy with his own scholarship and projects (and sometimes while he is). He was perfect: another China scholar, but one who works in a very different area than me, so he was coming in as another specialist, but one who would also pick up on all the stuff that isn’t obvious unless you’ve spent a decade mired in the minutia of drama reform in the PRC (which is probably 5 people on Earth, me included). Meticulous, funny (some of his marginalia still makes me laugh), fast, thorough, and even had an eye for when some translation was a bit wonky. I’m not joking when I say the only reason I managed to get the book turned around in 2 months — and one reason that I am so pleased with it — is because of his hard work on it.

I will admit that it felt a little weird initially to be paying a friend — a real, true, genuine friend — $XX an hour to edit my book. I was happy to do it, of course, but we’re not used to paying friends! I had a revelation few months ago, when someone on Twitter trotted out that old chestnut that “no one will ever look at your work as closely as your dissertation advisors ever again!” and lamented that this somehow signaled a lack of collegiality. The truth of the matter is editing — the kind of intensive editing that advisors often do, and a paid editor does — is work. It is hard work. Our advisors were getting some recompense for it through their salaries (if they were in fact doing that kind of editing — mine were, but I know many don’t). Our friends & colleagues are not. Here’s what Eric did for me (and what I did for a colleague, plus copy editing, though I wasn’t paid & and I will never do work like that ever again without being paid) through his marginalia, suggestions, and emails to me (all of which were extensive & I don’t mean a sentence or two), after reading (a) the reader reports (b) my response to the press and (c) the manuscript itself:

- Untangled my arguments

- Reorganized arguments, paragraphs, chapters that

helped clarify and heighten my argument - Raised questions in areas that were unclear that

helped focus my revising attention - Rephrased clunky sentences

- Suggested alternate translations

- Fixed typos

- Suggested scholarship and ways to connect

literatures I hadn’t even thought of to my argument (this was actually very

important with regard to the reader reports) - Did all of this & more over and over and over again over the course of two months on often

insane deadlines I threw at him.

What this experience taught me is that it’s important to professionalize this kind of relationship (I mean our editing relationship, not our friendship, of course!). Eric tracking his hours and sending me invoices and me paying him when I got the invoice put us into a relationship where I really recognized the actual, monetary value of what he was doing (which isn’t to say I don’t recognize the actual value of, for instance, workshopping things together (for free) or asking a colleague to take a gander at an article — of course I do! It’s part of the reason I like being an academic. It is valuable!). It doesn’t mean I won’t read things for friends and colleagues & offer feedback (for free) — of course I will! I love reading things outside (and inside) my wheelhouse and I love helping people. But I will never expect someone to do the kind of intensive work Eric did for me (and other editors do for other people) for free. It’s not fair to expect that. I’ve done it before for free, and frankly, I still sort of resent that I allowed myself to do all that for free, because I was trying so hard to be a good colleague and friend. We do so much unpaid labor in this profession, and it often means that those contributions are not “counted” or taken seriously. Editing is work. To do good edits is a lot of work. Someone not doing this amount of work, unpaid, does not make them uncollegial, it makes them a sensible human being.

Professionalizing our editing relationship also meant that I was much more comfortable going “Alright, ground through revisions on this yesterday, what do you think?” & expecting a relatively speedy response. Why? Because I was paying him. I suppose this might sound crass, but we jointly attached a monetary value to his time on an hourly basis, so I was somewhere on his work priority list & not down at the bottom of “oh god more unpaid labor I need to do on top of the other unpaid labor we’re all expected to do and when do I get to sleep” list. It also meant — because I had these eyes that I didn’t have to wait long for — I made some decisions that I don’t think I ever would’ve been brave enough to do on my own. The greatest example of this was Chapter 3: “Old Trees Blooming: Li Huiniang, Ghost Literature, and the Early 1960s,” which absolutely defines for me why turning a dissertation into a book is actually quite difficult.

It’s the oldest chapter & really the foundation for everything that followed. My first foray into ghost opera in the high socialist period was through Meng Chao & his Li Huiniang. My first published article was on Meng Chao & Li Huiniang — and it was a very conventional reading (hey, I was a second year grad student), but a very detailed one, of what were/are an understudied play & author. Tang Xiaobing noted the fact it was very conventional when I sent him my two sample chapters. But obviously, I felt it was strong, hence why I sent it — I published an article in Modern Chinese Literature & Culture, after all! I was having trouble seeing the forest for the trees, partially because it was the base (so I have a lot of sentimental and intellectual attachment to it), partially because it was the chapter I never had to fuss with much, because it was the oldest and most refined in some ways. That was actually the problem: it was the oldest, and I never had to fuss with it much. It actually needed the most fussing, because it was the oldest and I had never fussed with it much. The rest of the book had grown and changed and become more sophisticated, my argument had shifted pretty radically, but this chapter remained in stasis.

Despite a primary & fundamental argument in the book that said that we shouldn’t just read plays like Li Huiniang in the context of the Great Leap Forward, I spent a lot of time in that chapter talking about -the Leap. It seemed so important. It was important in the historiography. It had been important in my first analysis of the play. But now I was undermining my own argument and muddying the waters. I knew all of this rationally, but I couldn’t figure out how to fix it. How could I write a book about the high socialist period and not write about the Leap in some detail? These plays had always been read in that context! Furthermore, how could I introduce an entirely different piece of literature (Stories About Not Being Afraid of Ghosts) and part of my argument in a satisfying manner, while still telling the story of Meng Chao & Li Huiniang — it just wasn’t gelling.

I told Eric this chapter was going to be the hardest for me, emotionally & intellectually, because it needed to be fixed and was a mess but I just didn’t know what to do. And so he read, and thought, and then came back: “This section just doesn’t work,” he said about the (lengthy) part of the Leap. “And I think we should move this section up here, and make some tweaks to the chapter introduction, and trim this, and move this little bit, and then do that.” I took a deep breath, and literally deleted my section on the Leap (pages and pages and pages). It was terrifying. I made the other suggested changes, I added a few other bits to make things flow better. Then I read over the chapter again, and -it worked?

After I sent my revisions back to Eric, he said “Wow! This [removing the entire section on the Leap] seems like a bold move for a historian of the PRC!”. But he also said the chapter as a whole really worked now. To be honest, I’m still terrified that someone’s going to come back and criticize me for that decision, but it needed to be done. But the only reason I was brave enough to do that is because I had a trusted editor reading my work right then, and going “Yeah, this works!”. I didn’t have to wait two weeks or a month for one of my overburdened friends to get back to me and say “I — think this is better?”. I had someone looking at it who was looking at it as an editor — a professional editor — and brought all that to bear on their suggestions and revisions. I don’t think it devalues our friendship at all that we entered into a professional, paid relationship & if anything, it proves how highly I think of him as a scholar and editor. He did a lot of labor on my work, and was rightly compensated for it. The book is so much better for having had him editing it, and I go to sleep a lot better at night knowing he was paid a fair rate for his work on it.

Last Thoughts for Now

I am legitimately pleased with the book. I sometimes go back and look at the final page proofs & though I’ve actually been really good at not obsessing over any issues, typos, whatever that may crop up, or fretting about its reception (all of which is amazing as someone who struggles terribly with anxiety) & and read over what I wrote. “I wrote that? Really? It’s so good.” I still cry — good tears, I wrote that and it’s beautiful tears — reading my coda (that reviewer A suggested I write, and that Eric smoothed out on less than 24 hours notice). It’s really easy to become beaten down in academia & I have spent most of my time in my early career feeling like a terrible historian, a terrible researcher, a terrible teacher, despite evidence to the contrary. So it’s nice to look at this and be happy. It’s a good little book. It’s my good little book. And a lot of people helped make it my good little book.

I cried a lot in this process. I’m someone that cries in any situation of emotional intensity & sometimes I cry because I’m so angry or so happy — which is an embarrassing and not great trait to have in our line of work, but I’ve got it, so I roll with it. I wear my heart on my sleeve, and I know my friends are tired of the emotionally transparent tweets and FB posts and whatever, but I’ve just tried to share the process, because it’s helped me to know that I’m not the only one who hasn’t sailed through this hellscape of publication. There’ve been tons of lows, but a lot of highs. Seeing the book through has been an absolute rollercoaster.

Publishing a book is not easy. It’s not easy for anyone, and I know my friends who have seemingly breezed through this process have also struggled. We should stop acting like publishing a book is easy (certainly, senior scholars should refrain from saying things like that in front of their junior colleagues who are bogged down in the process). With the current Stanford debacle ongoing, we really ought to know that in many respects, things are only getting harder, not easier, and it doesn’t matter how good your work is. Presses lose money on our books as they always have, but now they have to deal with administrations that think what they do isn’t important, or isn’t important enough to subsidize, despite the fact that many of our careers are built on publishing a book with a reputable academic press — presses are publishing less, it’s getting harder to secure contracts. And it’s just plain hard to transition from a dissertation to a book, and publishing a book is a very different beast than publishing an article; that process needs outside eyes, and the author needs help.

I don’t think my dissertation was awful — but it did need the work that was put into it, and I’m very grateful to have landed with a well-supported series that provided both a workshop and necessary subventions (which is why the paperback is that really reasonable & for an academic book – $24.95). I’m really grateful for having a series editor that really did believe in the promise of the book, and a press that has been very efficient, and an absolutely wonderful editor that I hired. I was amazed when I saw the final page proofs & realized that my book — this thing I have raged at and cried over and wondered if it was ever any good, or if I was just a sham — was going to be the very first book in this brand new UM series. If amazing scholars – full professors at Michigan & believe it’s good enough to be not just a book, but the first book in their new series, who am I to argue?

It’s honestly been one of the most emotionally fraught, terrifying things I’ve ever been through (and yes, I realize how privileged I am in being able to say that publishing a book is one of the worst things I’ve gone through). But I still remember how happy, and moved, and grateful I felt when I read the words the copy editor (someone who has presumably read a lot of these things) wrote and asked the production editor to pass on to me:

I enjoyed editing this book. It’s a well-rounded and full picture that combines history, biography, literature, and even some statistics. In some ways in seems like a simple story on the surface, but it’s actually quite deep, and moving. I loved the coda, how she brings out the various meanings of ghost and the connection to tradition, and the desire to escape into the past and to honor tradition while attempting to update old works for the present. It’s said of dissertations and books that the author has lived with it for a long period of time. She expresses this directly, and beautifully, in the coda. It’s also simply written, without excess wordiness, which to me is a sign of a good conclusion.

The book demonstrated her wide-ranging sympathy with all sides in the debates, her ability to see them with understanding and depth. She has not only deeply seen the historical context, but some of the poetry of the works she’s reviewing has influenced her writing. I can see why she’s a historian of literature. In an unfolding of a historical mystery, writers often telegraph the conclusion, but here, in the coda, it came as both a summing up and a genuine surprise.”

As my faithful (paid) editor Eric said, “Can they just put THAT on the back of the book?”

A renowned scholar in one of my fields suggested “Resisting Ghosts” as a title, because having ghosts in there would sell better & but I demurred. Ever since a friend suggested Resisting Spirits, I have totally loved it. It’s a multiple entendre for me – four, for the various facets found within the book. A fifth for me, the author – because I am a resisting spirit. I have survived.

Last week, I was the final speaker in our department’s grad student association speaker series (which also marked the last day of classes for AY 2015-2016, hooray!), called “Rough Cut” – designed to expose current grad students to research-in-progress. I had signed up much earlier in the semester, and as the date drew closer, I wondered: did the grad students really want to hear about my interventions into PRC history and the cultural history of 20th c. China? Sure, listening to how fully (or semi-fully) fledged scholars are working through projects-in-process is useful – but most of me was saying ‘This has very little overlap with what most of our grad students do, and they will listen politely and ultimately leave not having learned a whole hell of a lot of useful stuff.’ They’re a very nice bunch, but subjecting people I like to 20 or 30 minutes of talk on something they have little background in seemed … selfish, to say the least. So I decided to do something a little different – instead of talking through the intricacies of my research in process, I’d walk them through how I got from a 2nd year research paper, to a dissertation, to a manuscript in progress. At the very least, I might be able to drop a few pieces of advice that might prove useful – even to people doing work that’s radically different than mine, in area and in emphasis. It was quite possibly just as useless as talking about my research, and only my research; but the intent was, at the very least, to be a bit broader and more useful.

Last week, I was the final speaker in our department’s grad student association speaker series (which also marked the last day of classes for AY 2015-2016, hooray!), called “Rough Cut” – designed to expose current grad students to research-in-progress. I had signed up much earlier in the semester, and as the date drew closer, I wondered: did the grad students really want to hear about my interventions into PRC history and the cultural history of 20th c. China? Sure, listening to how fully (or semi-fully) fledged scholars are working through projects-in-process is useful – but most of me was saying ‘This has very little overlap with what most of our grad students do, and they will listen politely and ultimately leave not having learned a whole hell of a lot of useful stuff.’ They’re a very nice bunch, but subjecting people I like to 20 or 30 minutes of talk on something they have little background in seemed … selfish, to say the least. So I decided to do something a little different – instead of talking through the intricacies of my research in process, I’d walk them through how I got from a 2nd year research paper, to a dissertation, to a manuscript in progress. At the very least, I might be able to drop a few pieces of advice that might prove useful – even to people doing work that’s radically different than mine, in area and in emphasis. It was quite possibly just as useless as talking about my research, and only my research; but the intent was, at the very least, to be a bit broader and more useful. I ended the whole presentation with another, newer talisman – one of the most famous quotes from Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, “Manuscripts don’t burn.” At the end of my first year at MSU, a colleague recommended the novel to me – I’d never read it, and in truth, have shied away from fiction for years (that goes for films, too). Documentaries, non-fiction, non-Chinese-history-monographs and the like, fine – I have consumed a lot of those since I started grad school, but my affection for fiction had really waned. The Master and Margarita was one of the first novels I’d read in years, and I loved it. Part of it was the description of life in the Soviet socialist literary system: the first few chapters were so on point! I recognized all of it. I remember sending an email at 3 AM – having been up a good chunk of the evening and wee hours reading – to the colleague who had recommended it, saying how fabulous it was. The rest of the novel was just magical, and absurd, and utterly wonderful. I recently passed it off to a friend who just finished her dissertation a few weeks ago – she said she was overwhelmed with choices of novels to read now that she had time, and so I handed over my copy of Bulgakov’s masterpiece.

I ended the whole presentation with another, newer talisman – one of the most famous quotes from Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, “Manuscripts don’t burn.” At the end of my first year at MSU, a colleague recommended the novel to me – I’d never read it, and in truth, have shied away from fiction for years (that goes for films, too). Documentaries, non-fiction, non-Chinese-history-monographs and the like, fine – I have consumed a lot of those since I started grad school, but my affection for fiction had really waned. The Master and Margarita was one of the first novels I’d read in years, and I loved it. Part of it was the description of life in the Soviet socialist literary system: the first few chapters were so on point! I recognized all of it. I remember sending an email at 3 AM – having been up a good chunk of the evening and wee hours reading – to the colleague who had recommended it, saying how fabulous it was. The rest of the novel was just magical, and absurd, and utterly wonderful. I recently passed it off to a friend who just finished her dissertation a few weeks ago – she said she was overwhelmed with choices of novels to read now that she had time, and so I handed over my copy of Bulgakov’s masterpiece. stressful year by watching documentaries and other things that make me happy. There’s a wonderful line in the documentary Elusive Muse (the subject of which is Suzanne Farrell, the last great Balanchine muse – I’ve

stressful year by watching documentaries and other things that make me happy. There’s a wonderful line in the documentary Elusive Muse (the subject of which is Suzanne Farrell, the last great Balanchine muse – I’ve

In any case, coming off a semester that was a bit of a downer from multiple angles, I’m eager and ready to get back to the classroom. I am teaching one of my perennial favorites – Gender in Asia (pre-modern edition!) – and am so excited to be teaching with some of my very favorite things: the KagerÅ nikki, my beloved, battered Chinese women writer’s anthology (dog eared and marked up, a purchase I made in Taiwan before I even started grad school – for the then-princely sum of 1225NT, around $35), Chunhyang, Sei ShÅnagon, Susan Mann and Dorothy Ko’s scholarship …

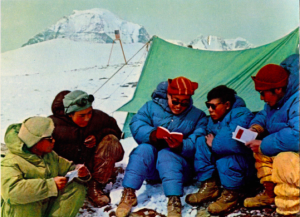

In any case, coming off a semester that was a bit of a downer from multiple angles, I’m eager and ready to get back to the classroom. I am teaching one of my perennial favorites – Gender in Asia (pre-modern edition!) – and am so excited to be teaching with some of my very favorite things: the KagerÅ nikki, my beloved, battered Chinese women writer’s anthology (dog eared and marked up, a purchase I made in Taiwan before I even started grad school – for the then-princely sum of 1225NT, around $35), Chunhyang, Sei ShÅnagon, Susan Mann and Dorothy Ko’s scholarship … In any case, I am really really really really really excited about this class (really. Really!). We have a whole whack of cool things to read, from classic narratives of first ascents and Western derring-do in exotic locales, to fascinating academic work like Sherry Ortner’s Life and Death on Mt. Everest. And a whole bunch of other things besides – Daphne du Maurier’s haunting novella “Monte Verità ,” news articles, academic articles on … eating and shitting on Mt. Everest? But one of the most novel things about the course is that – for once – I actually have the opportunity to really blend my research and teaching lives.

In any case, I am really really really really really excited about this class (really. Really!). We have a whole whack of cool things to read, from classic narratives of first ascents and Western derring-do in exotic locales, to fascinating academic work like Sherry Ortner’s Life and Death on Mt. Everest. And a whole bunch of other things besides – Daphne du Maurier’s haunting novella “Monte Verità ,” news articles, academic articles on … eating and shitting on Mt. Everest? But one of the most novel things about the course is that – for once – I actually have the opportunity to really blend my research and teaching lives.

I have a whole whack of backlogged posts-to-write that I haven’t gotten around to: the end of spring semester (the end of my second year as a full-fledged assistant professor!) was full and busy. Two conferences, including a trip to Canada, thoughts on teaching an experimental-for-me course, other assorted bits of my life. Frankly, as summer slides by – as it’s wont to do when you’re an academic, I was at the dentist a few weeks ago & the hygienist said to me ‘It must be so nice to have the whole summer off!’, and I could only laugh, because it’s not quite that simple – every day means it’s less likely for me to go back and write those posts, or finish the half-written ones in my queue. I may sit on quiet, cool nights and tap through my phone, looking at photographs and little snippets of video that make me smile, but I don’t really want to write about them. But a past of mine that passed into history long ago: well, that’s a little easier to write about. A little more like writing proper history.

I have a whole whack of backlogged posts-to-write that I haven’t gotten around to: the end of spring semester (the end of my second year as a full-fledged assistant professor!) was full and busy. Two conferences, including a trip to Canada, thoughts on teaching an experimental-for-me course, other assorted bits of my life. Frankly, as summer slides by – as it’s wont to do when you’re an academic, I was at the dentist a few weeks ago & the hygienist said to me ‘It must be so nice to have the whole summer off!’, and I could only laugh, because it’s not quite that simple – every day means it’s less likely for me to go back and write those posts, or finish the half-written ones in my queue. I may sit on quiet, cool nights and tap through my phone, looking at photographs and little snippets of video that make me smile, but I don’t really want to write about them. But a past of mine that passed into history long ago: well, that’s a little easier to write about. A little more like writing proper history. The game related to 7 that was mine was a PSP spinoff released in 2008, Crisis Core. It’s a beautiful little game in a lot of ways. I got it not because I was so attached to 7, but because I had played 7 & was curious about how Square was going to deal with a game where you knew the outcome before you started playing. I had also lived in Taiwan between 2006 & 2007, when FFVII prequel mania was at its height – my terrible little bathroom in my terrible (but wonderful) little rooftop one room studio with no kitchen had a FFVII prequel wall hanging in it (bathroom not shown here, but you get the idea). Crisis Core is a game where the main character is one that you know is dead in 7, the game that comes after. How does a writer deal with that? Can you write a satisfying story where everyone – well, everyone that had played the main game, which is the target audience here – playing it knows the character you’re playing is going to die? They did. I cried at the end – an end I knew I was coming. Maybe that’s why I liked it: it was like writing history with a sad end, where you know things are going to end badly.

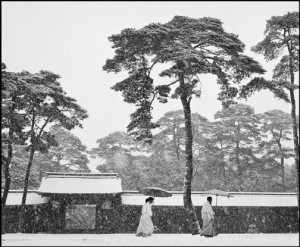

The game related to 7 that was mine was a PSP spinoff released in 2008, Crisis Core. It’s a beautiful little game in a lot of ways. I got it not because I was so attached to 7, but because I had played 7 & was curious about how Square was going to deal with a game where you knew the outcome before you started playing. I had also lived in Taiwan between 2006 & 2007, when FFVII prequel mania was at its height – my terrible little bathroom in my terrible (but wonderful) little rooftop one room studio with no kitchen had a FFVII prequel wall hanging in it (bathroom not shown here, but you get the idea). Crisis Core is a game where the main character is one that you know is dead in 7, the game that comes after. How does a writer deal with that? Can you write a satisfying story where everyone – well, everyone that had played the main game, which is the target audience here – playing it knows the character you’re playing is going to die? They did. I cried at the end – an end I knew I was coming. Maybe that’s why I liked it: it was like writing history with a sad end, where you know things are going to end badly. I played it on a PSP that I had bought myself on a whim the Christmas of ’07, at the end of my first quarter of grad school: I remember getting on the highway & driving down to the area with all the big box stores so I could go to GameStop. I came home with a trusty black PSP, which remained trusty and well-traveled until it was replaced with a Vita this year, long after it had become obsolete. It lives in my basement still, in its nice case, the kind that you could insert your own image into – which I carefully trimmed a photograph of the Meiji Temple in winter to fit, from my beautiful Christmas cards I used while I was in coursework. The interior simply said Peace. I still have a few in a desk drawer in my home office; I couldn’t bring myself to use all of them. I tried to find a case like that for my DS or Vita, because I just wanted to carry that beautiful image again, and I came up empty. That case (and PSP) went all over the US & to China (and various points in between), and now lives in my basement, mostly forgotten.

I played it on a PSP that I had bought myself on a whim the Christmas of ’07, at the end of my first quarter of grad school: I remember getting on the highway & driving down to the area with all the big box stores so I could go to GameStop. I came home with a trusty black PSP, which remained trusty and well-traveled until it was replaced with a Vita this year, long after it had become obsolete. It lives in my basement still, in its nice case, the kind that you could insert your own image into – which I carefully trimmed a photograph of the Meiji Temple in winter to fit, from my beautiful Christmas cards I used while I was in coursework. The interior simply said Peace. I still have a few in a desk drawer in my home office; I couldn’t bring myself to use all of them. I tried to find a case like that for my DS or Vita, because I just wanted to carry that beautiful image again, and I came up empty. That case (and PSP) went all over the US & to China (and various points in between), and now lives in my basement, mostly forgotten. I haven’t read it in years. But I remember saving a tab in my browser after it was published (where? I don’t even remember – maybe it was just on her Sexyvideogameland blog, the one that I linked to over and over when I wrote for Kotaku), and going back to look and look again, like I always do with good writing. In it, she talked about playing this game, this prequel to a game that had meant so much to her, and playing it while in the midsts of a relationship that was breaking down. And it wasn’t just that she was playing through this game where you know the main character is going to die, where the designers are deliberately making your heart stop with all these echoes of the game before, the game you are so attached to. But that original game formed the basis of that relationship that was breaking down. She wrote of this dying relationship, and silently passing the PSP between them, looking at this end-beginning – whatever one would term a prequel – that you know is going to end badly, at least for the current incarnation. And you have something here, in the right now, that is ending badly. But it’s a start, too: something new. It isn’t just the past replaying itself again and again.

I haven’t read it in years. But I remember saving a tab in my browser after it was published (where? I don’t even remember – maybe it was just on her Sexyvideogameland blog, the one that I linked to over and over when I wrote for Kotaku), and going back to look and look again, like I always do with good writing. In it, she talked about playing this game, this prequel to a game that had meant so much to her, and playing it while in the midsts of a relationship that was breaking down. And it wasn’t just that she was playing through this game where you know the main character is going to die, where the designers are deliberately making your heart stop with all these echoes of the game before, the game you are so attached to. But that original game formed the basis of that relationship that was breaking down. She wrote of this dying relationship, and silently passing the PSP between them, looking at this end-beginning – whatever one would term a prequel – that you know is going to end badly, at least for the current incarnation. And you have something here, in the right now, that is ending badly. But it’s a start, too: something new. It isn’t just the past replaying itself again and again.

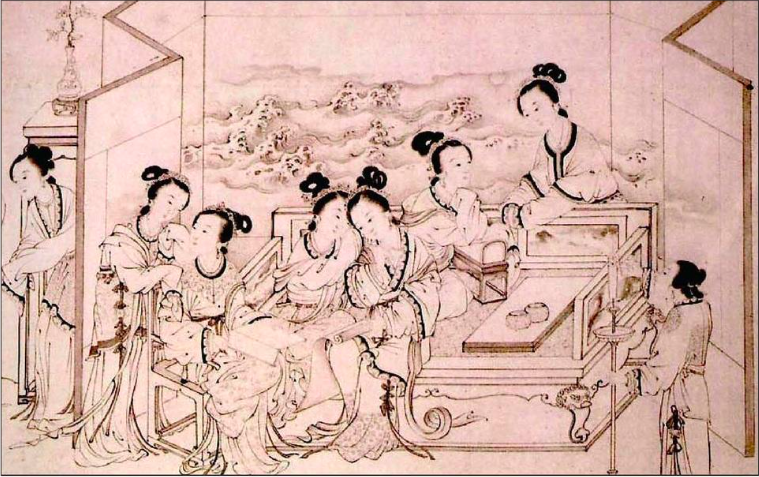

actually happen – another star serves as the “bridge”). This has, as far as I know, turned into some bizarre Valentine’s Day spin-off (at least partially), but originally, it was a celebration of women’s work (one of its alternate names is the Qiqiaojie 乞巧节, the ‘Begging for Skills Festival,’ referencing domestic skills & the practice of qiqiao 乞巧, making offerings to the Weaving Girl and holding competitions related to domestic tasks, like threading needles only by the light of the moon) & also one hoping for love or celebrating bonds. Or for missing lovers who were absent – not uncommon, at least among the poetry-writing literati, when husbands were not infrequently off on far-flung bureaucratic assignments and the like. In any case, it’s always struck me as a good deal mopier than Valentine’s Day, for the coupled and singled alike.

actually happen – another star serves as the “bridge”). This has, as far as I know, turned into some bizarre Valentine’s Day spin-off (at least partially), but originally, it was a celebration of women’s work (one of its alternate names is the Qiqiaojie 乞巧节, the ‘Begging for Skills Festival,’ referencing domestic skills & the practice of qiqiao 乞巧, making offerings to the Weaving Girl and holding competitions related to domestic tasks, like threading needles only by the light of the moon) & also one hoping for love or celebrating bonds. Or for missing lovers who were absent – not uncommon, at least among the poetry-writing literati, when husbands were not infrequently off on far-flung bureaucratic assignments and the like. In any case, it’s always struck me as a good deal mopier than Valentine’s Day, for the coupled and singled alike.

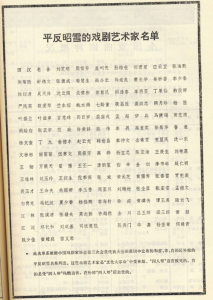

When I started looking more seriously at older parts of the historiography, I realized the field had spent some time sorting many of these people into various categories. “Establishment” intellectuals, for instance, or “revolutionary” intellectuals. These divisions can be useful, to a point; but they can also obscure a larger point, which is there was frequently a lot more similarities between these people than sorting them into different “camps” would lead you to believe. I don’t mean to imply I think there weren’t differences, or that seemingly minor differences don’t have an impact. As the political trials and travails of the 1950s and early 1960s – never mind the Cultural Revolution – indicate, there were camps, and your opinion on certain matters could have deadly consequences. But at the same time, from a distance of 70 years, there are a lot more similarities than differences. All of the people in my 1951 debate, for instance, agreed that China’s traditional culture was important and should be preserved. They disagreed on what that preservation should look like (among other things). But they agreed on one of the most important things of all: that this was worth arguing about, fighting over.

When I started looking more seriously at older parts of the historiography, I realized the field had spent some time sorting many of these people into various categories. “Establishment” intellectuals, for instance, or “revolutionary” intellectuals. These divisions can be useful, to a point; but they can also obscure a larger point, which is there was frequently a lot more similarities between these people than sorting them into different “camps” would lead you to believe. I don’t mean to imply I think there weren’t differences, or that seemingly minor differences don’t have an impact. As the political trials and travails of the 1950s and early 1960s – never mind the Cultural Revolution – indicate, there were camps, and your opinion on certain matters could have deadly consequences. But at the same time, from a distance of 70 years, there are a lot more similarities than differences. All of the people in my 1951 debate, for instance, agreed that China’s traditional culture was important and should be preserved. They disagreed on what that preservation should look like (among other things). But they agreed on one of the most important things of all: that this was worth arguing about, fighting over.

One of the most important commandments as a historian is “Do no violence to your sources”; treat them carefully, analyze them thoughtfully, be aware of what you are bringing to your interpretation. It seems that much more important when dealing with a life, especially a life that has been so little looked at in comparison to his peers. Knitting together these disparate pieces of a literary life makes me nervous, and I wonder sometime if I’m too likely to sympathize with men like Meng Chao (after all, Li Huiniang or not, he was part of The System that took root; surely he – and his compatriots – shoulder some of the burden for the disasters that came later, even if they themselves were swept up in them?). But he’s a very human actor to me, one that reminds me that all these other names and people (and scores of anonymous people besides) were people, and these were lives, and ultimately that’s the important part of the story – not abstract ideology or theory. One of my favorite pieces I ever wrote was for The Appendix, called

One of the most important commandments as a historian is “Do no violence to your sources”; treat them carefully, analyze them thoughtfully, be aware of what you are bringing to your interpretation. It seems that much more important when dealing with a life, especially a life that has been so little looked at in comparison to his peers. Knitting together these disparate pieces of a literary life makes me nervous, and I wonder sometime if I’m too likely to sympathize with men like Meng Chao (after all, Li Huiniang or not, he was part of The System that took root; surely he – and his compatriots – shoulder some of the burden for the disasters that came later, even if they themselves were swept up in them?). But he’s a very human actor to me, one that reminds me that all these other names and people (and scores of anonymous people besides) were people, and these were lives, and ultimately that’s the important part of the story – not abstract ideology or theory. One of my favorite pieces I ever wrote was for The Appendix, called

As I’ve noted before, academia can be full of pretty strange transitions – the leap from grad student to professor is an enormous one. A year and a half in, and I can say with some confidence I’m getting settled, but of course – this is not an overnight process. I’m lucky to be at a university where I have a lot of latitude with my teaching, so in addition to drilling down on my core classes (like the general modern East Asian history survey course, which I teach once a year), I’ve been experimenting with classes I may or may not ever teach again. But just because I don’t get a perfectly working syllabus out of a course doesn’t mean it’s a waste of a prep. I taught a slightly harebrained course on memory & culture in 20th century East Asia this past fall, and while I don’t think I’d ever try and do that again (at least, not as I had it set up!), I did get some fantastic feedback from my students regarding readings and films, general structure and themes, etc. that I will be incorporating into future courses. I try hard to be upfront with my students that a lot of things (like their professor) are works in progress & like soliciting feedback on what they liked (or didn’t), and I’ve generally been rewarded with really helpful commentary. So at least at the end of a semester, I can usually say I went out on a limb, it didn’t entirely work, but hey: I learned a lot & next time will be better.

As I’ve noted before, academia can be full of pretty strange transitions – the leap from grad student to professor is an enormous one. A year and a half in, and I can say with some confidence I’m getting settled, but of course – this is not an overnight process. I’m lucky to be at a university where I have a lot of latitude with my teaching, so in addition to drilling down on my core classes (like the general modern East Asian history survey course, which I teach once a year), I’ve been experimenting with classes I may or may not ever teach again. But just because I don’t get a perfectly working syllabus out of a course doesn’t mean it’s a waste of a prep. I taught a slightly harebrained course on memory & culture in 20th century East Asia this past fall, and while I don’t think I’d ever try and do that again (at least, not as I had it set up!), I did get some fantastic feedback from my students regarding readings and films, general structure and themes, etc. that I will be incorporating into future courses. I try hard to be upfront with my students that a lot of things (like their professor) are works in progress & like soliciting feedback on what they liked (or didn’t), and I’ve generally been rewarded with really helpful commentary. So at least at the end of a semester, I can usually say I went out on a limb, it didn’t entirely work, but hey: I learned a lot & next time will be better.

Well, 2014 was a pretty exciting year for this blog: my little post on

Well, 2014 was a pretty exciting year for this blog: my little post on