I took the first week and a half of winter break to go on one of my every-nine-months-or-so gaming binges – doing the media consumption equivalent of gorging one’s self during the holidays on delicious treats with little thought to anything or anyone else (or your waistline). I played through Tales of Xillia, having played about 3/4s over spring break last year, and its sequel, Tales of Xillia 2. I do love a good JRPG – it’s one of the few genres I’ve been playing consistently – and consistently seek out – since I started “really” playing games in the late ’90s – and it occurred to me that I’ve actually played a lot of the Tales of series. They feature a pretty frenetic battle style that isn’t actually my preferred way of play (boring, old school turn based battle is my favorite!), but there’s a pleasant rhythm and often plenty of game-sanctioned grinding via side quests. I’m one of those people that loves to grind, although not if I feel like I have to do it to progress in the game; but generally, I play games to put myself into a happy space, and low-stress, repetitive-task activities (cross stitch! Organizing things! Fixing footnotes! Grinding in an RPG!) do that for me.

In any case, I liked both the Xillia entries. I was a little suspicious of the second installment when I first started, since I don’t particularly like a silent protagonist, which Xillia 2 mostly has. My concern was perhaps heightened by the fact that I find random grunts, sighs, and other vocalizations – in absence of any other sort of voice acting – a bit irksome; at least in Persona, say, or Suikoden, the silent protagonist is, well, silent. After playing a game, I usually go poke around review sites, discussion boards, etc., just to see what conversation surrounding the game is like (I don’t tend to be playing the latest & greatest – or even popular – so thoughtful, focused criticism can be hard to find). I did so with the Xillia games, and was most interested in chatter surrounding the plot/ends of Xillia 2. There are three endings, which I guess are never officially named as “true,” “good,” and “bad,” but do seem to have some ranking, based on the kind of end credits given to each – well, the “bad” ending is rather clearly not the intended ending, since you never get to the end, and the battle to get to that ending is monstrously hard – far more difficult than the “final boss” in either of the other endings.

In any case, I liked both the Xillia entries. I was a little suspicious of the second installment when I first started, since I don’t particularly like a silent protagonist, which Xillia 2 mostly has. My concern was perhaps heightened by the fact that I find random grunts, sighs, and other vocalizations – in absence of any other sort of voice acting – a bit irksome; at least in Persona, say, or Suikoden, the silent protagonist is, well, silent. After playing a game, I usually go poke around review sites, discussion boards, etc., just to see what conversation surrounding the game is like (I don’t tend to be playing the latest & greatest – or even popular – so thoughtful, focused criticism can be hard to find). I did so with the Xillia games, and was most interested in chatter surrounding the plot/ends of Xillia 2. There are three endings, which I guess are never officially named as “true,” “good,” and “bad,” but do seem to have some ranking, based on the kind of end credits given to each – well, the “bad” ending is rather clearly not the intended ending, since you never get to the end, and the battle to get to that ending is monstrously hard – far more difficult than the “final boss” in either of the other endings.

JRPGs often get castigated for being totally predictable, and it’s generally true (although I don’t know that most other genres aren’t equally as predictable) – you know you’re probably going to be facing down some big evil with a motley collection of people, there’s going to be criticism of organized religion and/or environmental destruction and/or technology, there’s probably going to be some kind of betrayal along the way, one of the good guys will turn out to be bad or vice versa, things are probably going to resolve well for our band of heroes, and so on. I actually don’t mind the repetitive nature, but this may be somewhat linked to what I study. Drama in China was recycled from generation to generation; the same source material provided inspiration for centuries worth of cultural production. Consider the proliferation of Romance of the Three Kingdoms-themed games in East Asia: the medium may be new, but the popularity is not. There are patterns of narrative that can be comfortably inhabited; they don’t tend to be “shocking” or introduce anything new, but if the writing is good & characterizations are on point, well – a solid story is a solid story, even if it is rehashing ground we’ve been over before. I’m also willing to suspend my disbelief at everything if I like the gameplay and other elements (there are limits though: once, after Final Fantasy XIII was released, I was talking to a friend about the skill leveling system, which seemed a little ridiculous and over the top to me, and finally said “Are we just getting too old and jaded for this stuff?” “Yes,” he responded, not missing a beat, “Yes, we are.” But had I liked everything else about the game, I probably could’ve – would’ve – forgiven the “Crystarium”).

Xillia 2 wasn’t surprising exactly, but it was quite a bit darker than I was perhaps expecting. I was intrigued that none of the endings were really “fan service” endings – meaning happy in the sense of everything being resolved perfectly and easily. Many people liked this (it seems more mature, more realistic), many other people seemed to find it unsatisfying (where’s my happy ending, dammit!). In Chinese literature, there is a plot structure called datuanyuan 大团圆 (the “grand denouement,” “big and happy reunion,” a version of “… and they all lived happily ever after.”): the perfect, full-circle ending where the boy gets the girl, and the job, and everything else. No loose ends anywhere, and we all walk away with the warm fuzzies. I’ve been pondering the appeal of traditional literature – rife with datuanyuan, among other things – in high socialist China, and something about these Xillia 2 endings (somewhat happy, in some cases, or moving, perhaps, but not perfect in the sense that some fans long for: any option means cutting off some possibility, some person) spoke to my intellectual side a bit. Funnily enough, the “good” (but not “true”) ending in Xillia 2 is “round” in many respects, largely because of the game’s plot point about “alternate dimensions”: there is a certain amount of “things coming full circle” due to the alternate timelines and overlapping histories. But it’s not “round” in the sense of a datuanyuan – things don’t entirely work out as they “should” for a clear cut, unimpeachably happy ending.

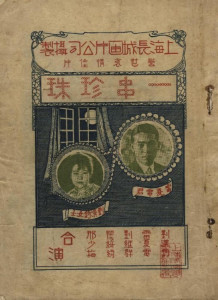

The datuanyuan is not some minor point for children’s fairytales (something I think we tend to associate the “and then they lived happily ever after” endings with – “grownup” media should be grittier, or more complex, and not so happy against all  odds); it’s actually quite an important thing in Chinese literature, including some of the greatest things ever written in any language. The English translation doesn’t convey the cultural significance of roundness (as Zhang Zhen notes in An Amorous History of the Silver Screen: Shanghai Cinema, 1896-1937, the significance of datuanyuan goes way beyond a cliché, and points to a kind of cultural conditioning – she mentions, for instance, the importance of visual cues like the typical round table used for family meals, as well as cosmological symbols like the full moon, in early Chinese cinema that had a tendency to rely on the “big reunion” as a plot structure). Cultural resonance or not, forcing a datuanyuan sometimes leads to bizarre results, like in the 1926 film A String of Pearls (Yi chuan zhenzhu 一串çç ), based loosely (and I do mean “loosely”) on the famous Guy de Maupassant short story “La parure” (The necklace), where the emotional punch of the story is more or less removed by an effort to ensure the happy ending. I suppose this is one complaint with happy endings in games; they can seem contrived or leave massive plot holes.

odds); it’s actually quite an important thing in Chinese literature, including some of the greatest things ever written in any language. The English translation doesn’t convey the cultural significance of roundness (as Zhang Zhen notes in An Amorous History of the Silver Screen: Shanghai Cinema, 1896-1937, the significance of datuanyuan goes way beyond a cliché, and points to a kind of cultural conditioning – she mentions, for instance, the importance of visual cues like the typical round table used for family meals, as well as cosmological symbols like the full moon, in early Chinese cinema that had a tendency to rely on the “big reunion” as a plot structure). Cultural resonance or not, forcing a datuanyuan sometimes leads to bizarre results, like in the 1926 film A String of Pearls (Yi chuan zhenzhu 一串çç ), based loosely (and I do mean “loosely”) on the famous Guy de Maupassant short story “La parure” (The necklace), where the emotional punch of the story is more or less removed by an effort to ensure the happy ending. I suppose this is one complaint with happy endings in games; they can seem contrived or leave massive plot holes.

There are also old examples of “fanfic,” intended to write the wrongs of an original narrative, or flesh things out (often appending a datuanyuan) – the ones I think of are related to Dream of the Red Chamber [Honglou meng 红楼梦], the 18th century novel by Cao Xueqin 曹雪芹. The first printed version (in 1791) included 40 extra chapters that don’t exist in earlier manuscripts, and there’s been a great amount of debate about what the ending should have looked like, who wrote the extra 40 chapters, the role of the editors of the printed version, etc (indeed, there is an entirely discipline dedicated to study of this novel – called Hongxue çº¢å¦ in Chinese, “Redology” – a tidbit that I still delight in passing on to students). The 19th century saw all sorts of new endings put forth, though as Jin Feng points out in Romancing the Internet: Producing and Consuming Chinese Web Romance, these have not generally been looked at from the angle of fan activity, but simply as part of pre-20th century literary production.

But of course, it’s not just fans who write happy, perfect endings. One argument about the datuanyuan – and it is a pretty constant feature of a lot of Chinese fiction over the centuries – is that Chinese fiction was initially “meant to entertain the writer himself more than his readers” (Gu Mingdong, Chinese Theories of Fiction: A Non-Western Narrative System). On this, brilliant intellectuals pointed out in the 1950s and 1960s that even the heyday of Ming chuanqi produced works that were generally self-indulgent on the part of the author (the translator Yang Xianyi commented in the early ’60s that “feudal period literati” paid little attention to coherence or overall structure, instead weaving together a bunch of disparate plots into one sprawling mass of a story: in essence, writing what they wanted to write, regardless of the effect it gave their audience). Owing to the unlikely chances of truly succeeding in the civil service system, literati – the producers and consumers of fiction – used these cultural products to daydream; they daydreamed not of “realistic” endings, but of spectacularly perfect ones. In some respects, it’s a more ancient and literary version of fan fiction, though in this case, the source material is generally historical in nature.

In truth, I like most datuanyuan-type endings, at least in games. I don’t seek them out – and often, designers are more than happy to give us one, so it’s interesting when one doesn’t appear – but there’s something pleasing about them, even if they’re ridiculous. I loved Final Fantasy X – which did not have a datuanyuan denouement (I cried! I snuffled lightly at all three endings of Xillia 2, but I actually cried at the end of FFX), and it’s possible I loved it because it didn’t have a perfect ending – but at the same time, I loved Final Fantasy X-2 because it tacked a company-sanctioned happy ending on to everything. I got my bittersweet ending and everything being tied up in a neat, if not entirely logical, package at the end. This is one reason for multiple endings, I suppose (that and the illusion of choice) – give the people what they want, make everyone happy! Bittersweet, sad, happy? We’ve got you covered.

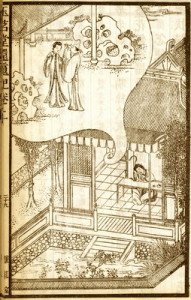

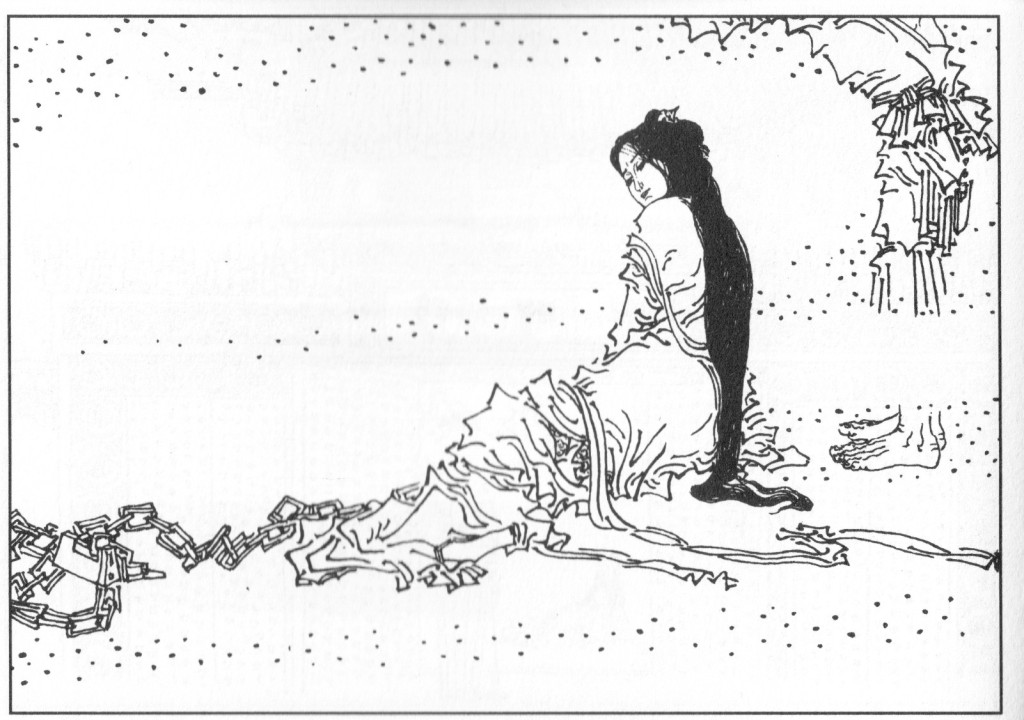

This is much harder to do in literature, for obvious reasons, although a single work can encompass all those moments. In drama, this is helped by the fact that the sprawling Ming tales were not performed in their entirety, and were instead seen in excerpts. Some of the most enduring parts of Tang Xianzu’s 汤显祖 masterwork The Peony Pavilion (Mudan ting 牡丹äº), or at least the ones that get trotted out the most, are not, in fact, the end, where everything works out – they are the beautiful and rather tragic (or at least bittersweet) early scenes. Considering the fears of moralists that chuanqi like Peony would drive women to madness, suicide, or worse, it seems that even having a happy ending was no guarantee your audience would gravitate towards that! Instead, portions of the reading audience seemed to fixate on the somewhat depressing (perhaps more realistic?) chapters – an acknowledgement that the datuanyuan was simply a fantasy, impossible in real life? The famous “Walking through the garden, waking from the dream” [Youyuan jingmeng 游å›æƒŠæ¢¦] section is rather wondrous – and it does feature quite the fantastic dream! – yet it’s simply that: a dream. And yet the (male) authors seemed to love writing the fantastical ending, no matter how improbable, even if those weren’t the parts segments of their audience gravitated towards. Perhaps this is partially a difference in producing and consuming; I wonder if fan-produced writing and art geared towards alternative paths or endings, fleshing out what happened after, writing a “perfect” scenario, whatever that might mean for an individual, often focuses more on the perhaps improbable yet perfect because it’s created largely to entertain one’s self and not really for an audience (publishing on fandom specific sites and the like notwithstanding) – not unlike some of the great fiction and drama in China.

This is much harder to do in literature, for obvious reasons, although a single work can encompass all those moments. In drama, this is helped by the fact that the sprawling Ming tales were not performed in their entirety, and were instead seen in excerpts. Some of the most enduring parts of Tang Xianzu’s 汤显祖 masterwork The Peony Pavilion (Mudan ting 牡丹äº), or at least the ones that get trotted out the most, are not, in fact, the end, where everything works out – they are the beautiful and rather tragic (or at least bittersweet) early scenes. Considering the fears of moralists that chuanqi like Peony would drive women to madness, suicide, or worse, it seems that even having a happy ending was no guarantee your audience would gravitate towards that! Instead, portions of the reading audience seemed to fixate on the somewhat depressing (perhaps more realistic?) chapters – an acknowledgement that the datuanyuan was simply a fantasy, impossible in real life? The famous “Walking through the garden, waking from the dream” [Youyuan jingmeng 游å›æƒŠæ¢¦] section is rather wondrous – and it does feature quite the fantastic dream! – yet it’s simply that: a dream. And yet the (male) authors seemed to love writing the fantastical ending, no matter how improbable, even if those weren’t the parts segments of their audience gravitated towards. Perhaps this is partially a difference in producing and consuming; I wonder if fan-produced writing and art geared towards alternative paths or endings, fleshing out what happened after, writing a “perfect” scenario, whatever that might mean for an individual, often focuses more on the perhaps improbable yet perfect because it’s created largely to entertain one’s self and not really for an audience (publishing on fandom specific sites and the like notwithstanding) – not unlike some of the great fiction and drama in China.

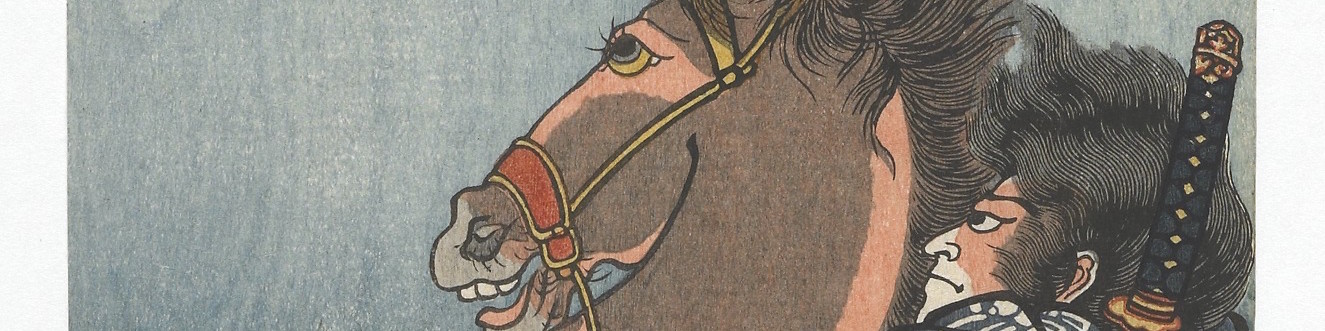

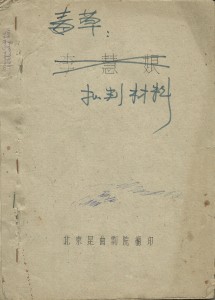

I’m interested in literary production as self-entertainment. While I don’t think my Marxist intellectuals were generally writing to entertain themselves (though I do think sinking one’s self into the full capabilities of classical Chinese – worlds away from rote Marxist language, more “understandable” vernacular – must have been a pleasure), I do think they were writing to entertain each other, at least in some cases – something that gets lost when we focus on ideological squabbles and high politics to the total exclusion of thinking about writing and consuming literature. I’m also interested in the fantasy of it, at least as applied to the historical dramas c. 1960 I write about. We focus so much on their political meaning – the coded, yet sharp, rebukes of a system that wasn’t working for vast amounts of the Chinese population – but what about their function as escapes? As daydreams? To be sure, “righteous phantasm raining down hellfire on cruel and unjust prime minister” (as in this image from Li Huiniang) is lacking a bit of the romance of “dead maiden revived for love of talented scholar, and everything works out in the end.” But on the other hand, it’s a fantasy of a very particular kind, well-suited for a specific moment. The act of creating or consuming such a fantasy in that moment could be quite powerful, I think. Consuming the fantastical can be powerful at any moment.

I’m interested in literary production as self-entertainment. While I don’t think my Marxist intellectuals were generally writing to entertain themselves (though I do think sinking one’s self into the full capabilities of classical Chinese – worlds away from rote Marxist language, more “understandable” vernacular – must have been a pleasure), I do think they were writing to entertain each other, at least in some cases – something that gets lost when we focus on ideological squabbles and high politics to the total exclusion of thinking about writing and consuming literature. I’m also interested in the fantasy of it, at least as applied to the historical dramas c. 1960 I write about. We focus so much on their political meaning – the coded, yet sharp, rebukes of a system that wasn’t working for vast amounts of the Chinese population – but what about their function as escapes? As daydreams? To be sure, “righteous phantasm raining down hellfire on cruel and unjust prime minister” (as in this image from Li Huiniang) is lacking a bit of the romance of “dead maiden revived for love of talented scholar, and everything works out in the end.” But on the other hand, it’s a fantasy of a very particular kind, well-suited for a specific moment. The act of creating or consuming such a fantasy in that moment could be quite powerful, I think. Consuming the fantastical can be powerful at any moment.

We sometimes act like a story with a “fairytale” ending is necessarily simplistic, juvenile, or unsophisticated; the history of the datuanyuan in China illustrates that such things can be quite sophisticated in terms of aesthetics and artistic value. I suppose I don’t place a huge amount of value on a “round” ending in the sense of datuanyuan (though the fangirl inside me does like them in games where I’m attached to the main characters), but I do place value on an ending feeling “round,” fleshed out, and coming to a conclusion in a graceful, logical way. Games are a bit of a fantastical daydream for me, or that’s how I use them – I suspend disbelief for so many other things, a happy “round” ending is just one more thing. Not so unlike my playwrights, I suspect – they were willing to suspend disbelief for that chance of escape and daydreaming, if only for the duration of a performance. Those few hours of being thrilled at the turn of events, of imagining some other path were worth any logical gymnastics they subjected themselves to.

Well, the

Well, the

Games are interesting to plonk down in this context, because we treat them very differently than, say, Chinese opera: they’re global in a way a lot of other cultural products aren’t, almost from their inception. In Yellow Music, Andrew Jones discusses the circulation of jazz (and technology) in a way that’s resonated strongly with me over the years (in a monograph that has the hands-down best conceptual use of “colonial modernity” I’ve ever come across). He notes that one African- American’s account of the Chinese jazz age of 1930’s Shanghai “alerts us to the folly of trying to understand Chinese jazz as an example of Western influence on Chinese musical forms. Nor can the ‘Chinese’ in ‘Chinese jazz’ be relegated to the realm of the merely adjectival ….” He further notes that we must “look at the ways in which both (and indeed all) parties have been and continue to be inextricably bound up in a larger and infinitely more complex process.” While we sometimes append some sort of national marker to games (the ‘Japanese’ in JRPGs springs to mind here), we frequently don’t – often because national origins are obscured through translation and localization, and a rather interesting process of naturalization.

Games are interesting to plonk down in this context, because we treat them very differently than, say, Chinese opera: they’re global in a way a lot of other cultural products aren’t, almost from their inception. In Yellow Music, Andrew Jones discusses the circulation of jazz (and technology) in a way that’s resonated strongly with me over the years (in a monograph that has the hands-down best conceptual use of “colonial modernity” I’ve ever come across). He notes that one African- American’s account of the Chinese jazz age of 1930’s Shanghai “alerts us to the folly of trying to understand Chinese jazz as an example of Western influence on Chinese musical forms. Nor can the ‘Chinese’ in ‘Chinese jazz’ be relegated to the realm of the merely adjectival ….” He further notes that we must “look at the ways in which both (and indeed all) parties have been and continue to be inextricably bound up in a larger and infinitely more complex process.” While we sometimes append some sort of national marker to games (the ‘Japanese’ in JRPGs springs to mind here), we frequently don’t – often because national origins are obscured through translation and localization, and a rather interesting process of naturalization.