I just finished my second week of school as an assistant professor, and while there is a lot of new happening in my life right now on all fronts (particularly professionally), I’m traversing a lot of relatively well known ground in my two courses. I haven’t gotten to the fun bits of my introductory course on modern East Asian history, but we’re trucking along in my “Modern China” course (which is, in point of fact, a course on the history of the PRC) and I’m coming back to old friends after a long time away from them.

I just finished my second week of school as an assistant professor, and while there is a lot of new happening in my life right now on all fronts (particularly professionally), I’m traversing a lot of relatively well known ground in my two courses. I haven’t gotten to the fun bits of my introductory course on modern East Asian history, but we’re trucking along in my “Modern China” course (which is, in point of fact, a course on the history of the PRC) and I’m coming back to old friends after a long time away from them.

This week, my students read bits of Li Dazhao, Chen Duxiu, and Lu Xun. As I admitted to them, the Lu Xun – “What Happens After Nora Leaves Home?” 娜拉走åŽæ€Žæ ·ï¼Ÿ- was a semi-selfish choice for me. It was a slightly out of place essay (we haven’t covered “the question of woman” in depth, unlike like the last time I taught the essay – which was on women in modern Chinese history). But I knew we wouldn’t have much time to spend on my favorite Republican writers, and really, while I would’ve liked for them to have read all sorts of things from Lu Xun (and a lot of others) – “Nora” was a ridiculously influential essay in my own life, and one that I think shows Lu Xun off to some of his best advantages. I’m not really overstating the case when I say that this one essay – actually a talk given at the Beijing Women’s Normal College in 1923 – is one of the primary reasons I became a Chinese historian. It was Lu Xun and Dorothy Ko’s account of Jiangnan women in the Ming-Qing period (Teachers of the Inner Chambers) that I really glommed on to – things that, for whatever reason, I connected with in a particular way that I hadn’t before in my other history classes. I later realized the incongruity of those two influences, but it probably has something to do with the way I’ve turned out as an historian.

“Nora,” perhaps because it’s an essay I’ve been reading for a long time, encapsulates for me the reasons I love Lu Xun: his pessimism, his snarkiness (is it any wonder that the man helped lift zawen into an art form?), his tendencies towards “There are these problems, here they are. Now you figure out how to fix them.” He’s not an optimist at all, nor does he claim to have all the answers (or any). I actually like that about him, especially considering the period he lived and worked in; it’s also interesting hearing how students respond to him. So many of the sources I give them have eternal faith and optimism in this inexorable march of progress – I think it’s a bit refreshing to hand them something that says: “Great, ‘modernity.’ And? Where exactly are we going with all this?”

The first time I “taught” Lu Xun (the first time I ever stood in front of a class of undergraduates as The Person In Charge, actually), I was left in charge of an upper division class for a day while the professor was at a conference. I had no idea what to do when told “Well, just go over ‘Diary of a Madman’ and ‘Ah Q’ and go from there,” and I’m sure many of those students still have no idea what to-do over Lu Xun is (maybe this is one reason I come back to “Nora”: I know what to do with the essay, and it’s one that I love talking about). I paced in front of the classroom, clutching my battered and coffee-stained copy of Lyell’s Diary of a Madman and Other Stories, begging the students to say something – anything. It was my first time realizing that dealing with fiction (or visual culture, or films, or whatever) in a historical manner is not as straightforward as I had thought it to be.

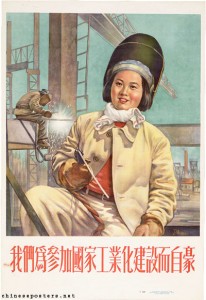

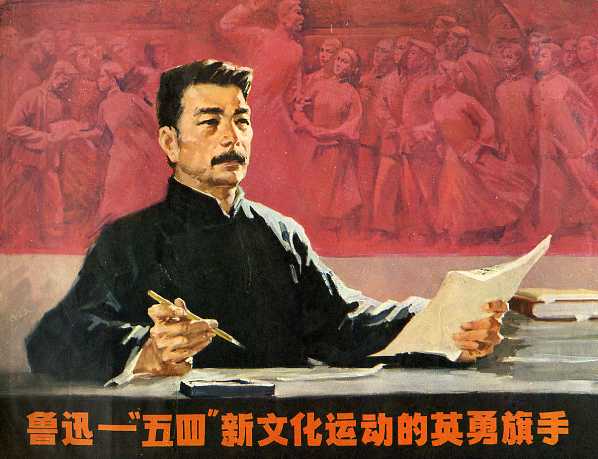

I still don’t know that I can adequately convey how much I love Lu Xun, and why, to my students, but I try. I show them my propaganda poster from 1974/5 (above), which has watched over me throughout grad school. I impress upon them how important he’s been in modern China, how revered – but also how dangerous his writings have been perceived as. One of my Chinese teachers in Taiwan related how she came to know Lu Xun, read surreptitiously in the period when his works were banned.

As it turned out, this was a good week to talk about Lu Xun – he’s back in the news again, because he’s continuing to disappear from textbooks on the Mainland. It’s interesting to watch this from a distance, and while I have no doubt that concerns over the government’s stance that “middle school students shouldn’t be doing too much deep thinking” are well founded, I also think it’s a little ridiculous to expect middle school students – Chinese or not – to “get” Lu Xun.

I once had an enlightening conversation with a friend – who was educated in the Chinese system through secondary school – about Lu Xun. I was bubbling enthusiastically about why I enjoyed reading him and how I always found something new when I came back to well-loved essays like “Nora.” “Oh,” she said, in a pretty bored manner, “I read that stuff when I was eleven.” I was a little taken aback, and a bit offended – of course I couldn’t be so blasé about having read Great Authors of Modern China at a young age, what American school kid could? – but a professor, also educated in China, said thoughtfully when I relayed this to him: “Well, don’t feel bad; he really is a giant & he’s said things that no one has said better since,” and also this, which I thought of when reading the recent kerfluffle. “It’s hard to appreciate it when the stuff is shoved down your throat from an early age.” I had a fundamentally different relationship with Lu Xun, and not just because I was American.

In sixth grade, we read Le Petit Prince. The joys of Saint-Exupéry were lost on me at that tender age; I thought it was an utterly stupid book. I mean, really – talking foxes and boys from outer space and bitchy roses? I read the book again as a senior in high school, this time in French, and I adored it – I “got” it in a way I couldn’t have, probably shouldn’t have, when it was being crammed down my throat, as it were. Of course, it was a children’s book in a way that Lu Xun’s works are not and never have been. But I think that general arc of needing a certain amount of maturity to really “get” something is rather similar.

Perhaps the government – in a scramble to prevent middle schoolers from thinking “too deeply” – is actually doing them (and all of us) a favor. Who, I wonder, got more out of Lu Xun: the 11 year old who had him and his status as a Great Writer force fed to them from a young age, or my Chinese teacher from Taipei who read him (with all the thrill of nibbling on forbidden fruit) at night, under the covers with a flashlight (OK, embellishing a bit there – but still! Forbidden or discouraged often equals desirable!)? I’ve watched American college students struggle with “Ah Q” and “Diary” and other writings of Lu Xun (and many other authors). I still struggle with him, much as I love him. I can only imagine what a 12 year old does when presented with one of these essays. Do they laugh at his wit and sarcasm? Ponder his pessimism? Or just consume him as they’ve been taught: reverently, or with sheer boredom? I’ve watched college students (even those, like many of mine here at MSU, who have very little experience with Asian or Chinese history and literature) ask thoughtful questions – deep questions – about his writing that I don’t think the average (or even the exceptional) eleven or thirteen or fifteen year old anywhere is ready to ask, or even think of.

My students asked questions about the very same things Lu Xun brings up in his most recently removed story, “The Kite”: forgetting, historical memory, and consequences. They also asked about dreaming for the future, holding on to the promise of Something Better if we just get through the terrible now (I was delighted with this, since it presages one of the more difficult texts I’m asking them to engage with this semester, Ci Jiwei’s Dialectic of the Chinese Revolution: From Utopianism to Hedonism). They were the kinds of questions with no easy answers, things that aren’t really designed to be answered right then – the type of response I want my students to have to him.

Lu Xun, and a lot of his compatriots, are special (I do not hang posters of average people on my walls, after all). I wonder if this process of moving Lu Xun back to that realm of the exceptional – the off-limits – won’t do more for his legacy than continuing to flog him to students at a young age. And do more for his would-be modern readers, at that. The great whip he wrote of will come; who knows, he may be a spark for that whip. But probably not if he’s continuously relegated to the heap of “boring crap we had to read in middle school.”

Unfortunately China is very hard to change. Just to move a table or overhaul a stove probably involves shedding blood; and even so, the change may not get made. Unless some great whip lashes her on the back, China will never budge. Such a whip is bound to come, I think. Whether good or bad, this whipping is bound to come. But where it will come from or how it will come I do not know exactly.

And here ends my talk. 1

For my nineteenth birthday, I bought myself a PlayStation 2 and a copy of Final Fantasy X. It was something of an impulse purchase, but I passed a nice week afterwards holed up on my first real gaming binge. While I’d played through the Final Fantasy offerings for PS1, FFX was the first of the series to really catch me, and it’s part of the reason I’m generally playing some JRPG or another, or nothing at all.

For my nineteenth birthday, I bought myself a PlayStation 2 and a copy of Final Fantasy X. It was something of an impulse purchase, but I passed a nice week afterwards holed up on my first real gaming binge. While I’d played through the Final Fantasy offerings for PS1, FFX was the first of the series to really catch me, and it’s part of the reason I’m generally playing some JRPG or another, or nothing at all.