Part I: The bare bones of it (sort of)

It’s quite strange to be writing openly about all of this, but I guess aspects of it have come up quite a lot since I left (not necessarily related to me in particular, but life at a blog like Kotaku in general). It’s a lot of navel-gazing and I feel a very silly and incredibly conceited in some respects, but in others it’s rather cathartic and useful to ruminate on that part of my life. So, apologies for the self indulgence spreading over two posts. It also occurs to me that I probably make too much over “page views,” but it was how our “success” was measured, and the way I got used to thinking of myself & how I fit into the larger picture of Kotaku and the gaming blogosphere.

a. On intellectual background

My workspace in San Diego, in the midsts of final editing of my 2nd year research paper. Can't wait to see what Ben Abraham & ANT have to say about this!

I grew up with an incredibly intellectual mother (who, while not a member of the academy, is a historian) who instilled in me a deep and abiding love for the wonderful, invisible, essential thing of history, and also a love of cultural “stuff.” This ranged from poetry to painting to music to architecture to furniture. I joke that I was raised to be a cultural historian. It’s not really a joke; it’s true. I would’ve had to work very hard to outrun my upbringing, and indeed – I tried on other things over the years and none of them quite fit. Certainly, the academic skill of approaching cultural production in a particular manner was honed in college, then further in grad school (and is an ongoing process), but the basics were there, I think, from a pretty young age.

My first independent intellectual passion was Latin. I now teach students who sometimes struggle with how to take a 9th century poem about some guy’s cat and apply it to their lectures and textbooks (not, admittedly, always the easiest thing to do); the leap from “literature” to “history” is not always a smooth one (this goes for films and music – and games – as well). My adventures in Roman literature taught me how to do that, or at least try. I didn’t just love Catullus because he was funny and sad and wrote beautiful poetry; I also loved Catullus because I could read his poetry and it said something about a subject I wanted to know more about, but it was up to me to dig that out. I started learning early on how to at least try and think critically about cultural production, and how it fit in with other topics.

It was my introduction to applying cultural production to historical studies. It was also the only reason I didn’t flunk out of high school, because while I was barely scraping by in most every other class (due to boredom and lack of interest, particularly when it came to things like “doing homework”), I never had trouble getting good marks in Latin. It even occurred to my mother, despairing over my future, that maybe since her offspring’s intellectual proclivities included translating authors who had been dead for 2,000 years and falling in love with Tolstoy, all was not yet lost. Sure enough, things improved dramatically after I got out of high school and on to better things, like college seminars on “masculinity and power in the US” and “Roman historians: Caesar, Livy, Suetonius.” So, gratias vobis ago, my wonderful Latin teachers, and my treasured old friends like Catullus and Horace and Vergil and Ovid – I wouldn’t be a Chinese historian if it weren’t for you. I wouldn’t have found a weird little niche on Kotaku if it hadn’t been for you.

The more I read, watched, and studied, the more I had a hard time shutting off the academic side of my brain that was constantly humming away in the background, analyzing and making connections – even when watching “fluff.” When I really started to play videogames, I approached them in much the same way I approached most every other piece of culture I consumed – and the intellectual side, likewise, didn’t really want to shut off. It was pretty natural, then, that I gravitated towards work that approached games similarly (though much more sophisticatedly) to the way that I wanted to approach cultural objects of all stripes.

b. On becoming a niche writer

I suspect, if one were to go back through my earliest posts for Kotaku, you would find that they were trying to play more to the general readership (I haven’t done this, but I have a vague feeling that’s what I was doing). Not because of any financial incentives, but I did want to make my boss and fellow writers happy and fit the mold, so to speak. At some point pretty early on, I realized my page views were dismal (though steadily increasing – but they never got close to the views that other writers on the site got) and short of me totally setting aside my personal interests, I was never going to be widely read. So I just started mining the blogs I liked, the things I read, the things that were interesting to me. And there was the practical matter I mentioned: other writers on the site weren’t posting from these sources, so there wasn’t the anxiety over ‘Oh no, they posted X, Y, and Z today that I was going to post.’

I did get lucky here: my boyfriend through most of my Kotaku tenure kept up on a lot of interesting things and introduced me to a number of blogs that would’ve taken me much longer to stumble upon on my own. Leigh Alexander’s Sexy Videogameland, for example, was one of these (so while I get all the credit for helping to solidify Leigh’s early readership, at least insofar as Kotaku writers are concerned, my ex deserves the real lion’s share of that! Thanks, Dave – I’m sure Leigh would thank you, too, if she could). Between the two of us, I managed to build up a pretty respectable list of feeds I kept up on, and a lot of it was very different than the average post on Kotaku. At some point it occurred to me in a more obvious manner that hey, I was posting stuff that wouldn’t be appearing on such a widely read site otherwise.

This is how I eventually wound up with a Mao Cow of my very own

That moment was probably when Ian Bogost IMed me to say “Thanks for posting my stuff.” After I got over my fangirlish reaction of “OMGOMGOMG, Ian Bogost is talking to me!” and “Why is he thanking me? He’s Ian freakin’ Bogost! His body of work is amazing,” I responded with something insipid like “Well, I don’t always agree with everything you say, but I really like your work” (dur).

But it dawned on me that if someone like Ian Bogost gave me a polite nod to say thanks for flinging traffic his way (though Ian is a nice guy, so maybe he was just being polite), maybe all this stuff did need a lot more exposure on a place like Kotaku than I thought. This is a double-edged sword, of course – I sometimes felt a little bad about throwing smaller blogs under the Kotaku bus. I think the really sharp work itself forms an interesting ecosystem and it chugs along just fine without directing the people who read Kotaku to it. Also, I knew people could be really nasty in comments and most of the writers weren’t asking me to link to their work – many of them were probably just as happy not to be involved with the wider blogosphere that Kotaku was part of. Ethics of blogging? In the end, I figured a lot of people who just wanted to say hateful things were frequently too lazy to actually go over to the other sites, and simply spewed their vitriol on Kotaku. Unexpected traffic could be a problem, I’m sure, but I just hoped it all balanced out in the end (and I think it did).

c. On becoming a Chinese historian and a niche writer

One of Abraham’s questions was on how grad school impacted my approach to my work on Kotaku. It did a couple of things, in retrospect – it put a new stress on a couple of issues that had been bubbling for me and introduced some new variables.

First, and probably most important, I told myself I would simply not post anything I would be embarrassed to have my academic reputation associated with. It wasn’t that I thought posting about porn stars and sexy cosplay and lowbrow humor was beneath me, but I just couldn’t imagine someone from my academic universe googling my name and coming up with posts like that. The fact I wrote about videogames was weird enough; writing about porn stars playing videogames would’ve been (would be) too much. While I posted plenty of things (including my own longform pieces) that weren’t up to quality standards set forth for our research projects, I’m not ashamed to have anyone I know in academia come across any of it. I once got (very kindly) nailed – before I got to grad school – for overestimating the anonymity and vastness of the internet (e.g., the ability to hide). And that was before I wound up with my name attached, in a very public manner, to things I was writing – so losing any hope of anonymity at all. It was an incredibly embarrassing flub, but a really valuable lesson to learn early on. I never wanted to embarrass my advisors and other people important to me in academia. It solidified my leanings towards esoterica. Unfounded worries? Perhaps; but it was something that certainly channeled my efforts away from certain directions.

Actually, let me clarify that: I would have posted about porn stars and sexy cosplay had it been framed in the right manner. There are plenty of smart ruminations on gender, sex, and all sorts of potentially “lowbrow” (in other manifestations) topics in the blogosphere, and I did post a lot of that. What I did not post were articles about scantily clad women making sometimes questionably informed comments about AAA titles I didn’t play, with an attached photo gallery of them rubbing themselves on a 360 controller or PSP (among other things, it just seems this is one type of post that raises ire on a semi-frequent basis). I don’t have a problem with that sort of stuff, I just wish people didn’t attempt to wrap it in the veneer of “But she’s a legitimate gamer, don’t you see!” Don’t try and “justify” it at all; it is what it is, just like a lot of what I wrote was boring – if not to me personally, then to large chunks of the readership. I didn’t try and make it something it wasn’t. I posted calls for papers that 99% of the Kotaku readership couldn’t have cared less about, and other people posted lingerie-clad women that insulted some of the readership. We did it because we could, we wanted to, we had the power to do such things, and we had posts to get out. That’s OK.

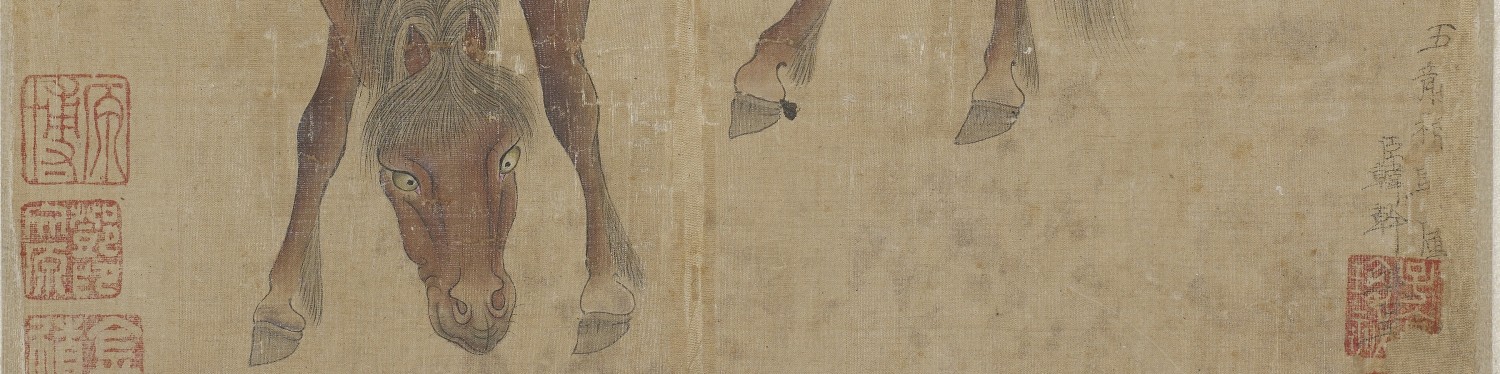

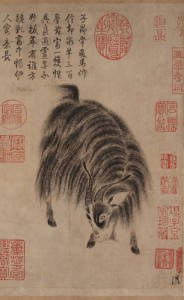

Goatgate was hardly as charming as this little fellow (Zhao Mengfu, detail from "Sheep & Goat," Yuan dynasty)

But generally, the “gimme” headlines just weren’t the stuff I wanted to post and weren’t the kinds of things I wanted my name (one that is still very, very young in academic terms) pulling up as a top hit when people googled me – so there was little reason for me to compete with coworkers for those coveted, attention-grabbing posts. Again, unfounded anxiety? Maybe. But I also have to say I found most of my “biggest” posts pretty unsatisfying – that is, the things that were way out of the zone of things I was interested in, but “someone” needed to post, and were attention grabbing enough to draw in more than my usual readers. The example I remember most clearly was the God of War “Goatgate” “scandal” (I use that term loosely). It got me a lot of page views that week, at least in terms of my usual – somewhere around 40,000 for that article alone. My general reaction was “meh.” It was sensational and dull all at the same time, and I just didn’t care all that much. Though I still cannot believe I used to have a job where I could post things with titles like “Sony Decapitates Goat, Raises Ire” and get paid for it. In essence, I generally posted things I was interested in and that I wanted to read. I don’t want to read about porn stars playing Madden. Why would I want to post it?

Anyways, that segues into page views, which are an obsessive part of working for a blog. On that particular aspect of writing, then, grad school did another thing for me. A lot has been made of the bonus system at Kotaku, which I have tried to explain elsewhere. When I first started writing there, I was paid a certain amount per post (which was predetermined – I did 12 posts a weekend, and that was that). There were quarterly bonuses, but those were tied to overall site traffic – beyond that, there was some sort of calculation on how much a writer had contributed to that traffic, and that determined your bonus. At some point (I don’t really remember when – a little less than a year into my tenure, maybe), there was a change in the bonus system – salaries were fixed, and then bonuses were paid to individuals based on their particular target number of page views. I never got one of those checks, so I don’t really know how it worked. I also want to underscore that my comments on this topic (both here and elsewhere) apply only to the time that I was working for Kotaku, between 2007 and 2008. I have no idea what the system is now, and I don’t want people inferring from my comments something that may or may not be the case about the current setup.

Salary was not, as has been incorrectly reported in multiple places, fixed to page views. I got the same amount of money every month, at least in base salary (and in practice, since I never had a lot of page views (thus no bonus), in total), regardless of whether I had 500,000 page views or 5. It’s a testament to Brian Crecente that he kept me on as long as he did, since I’m pretty sure my “underperformance” was a fireable offense in the Gawkerverse.

OK, what in the hell does Gawker’s bonus structure have to do with grad school? This is actually key to my blasé approach to page views (and why I wound up comfortably inhabiting a niche that was really unpopular compared to the bulk of the site). Kotaku wasn’t my full time job. I didn’t need it to make ends meet – I didn’t need it at all. I had a salary – because I was a PhD student. Yes, the money was absolutely very nice; I missed it when it went away – but I was never in danger of not being able to keep a roof over my head, or the dog in kibble, when it stopped. In my particular life situation, the carrot of a bonus proved utterly ineffective – I didn’t need it, and the pursuit of it would’ve meant turning away from the things I was really starting to enjoy by that point. I have always been mulish in my temperament, and the idea of a little bit of extra money (based on a system I never figured out in the first place) wasn’t worth abandoning what I was interested in. I dug in my little heels and basically ignored the fact that bonuses existed. If Brian had said, “Maggie, you’re really underperforming and this is a problem,” I would’ve had to reevaluate my stance. As it was, he never did, and I always had the impression that everyone thought my penchant for posting “weird” stuff that no one else did was, if not valuable, at least contributing something.

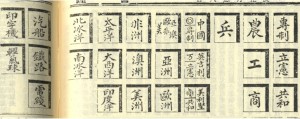

Would I have wound up writing on the 1904 "serious game" edition of mahjong without Kotaku? Probably not.

On a more personal level, actually starting my formal graduate studies combined with the crash course I did in game studies (when I started posting about it on Kotaku) and made me say “Hm, maybe this is something I ought to pursue.” Which of course led to me reading more, and thinking more, then reading more, then posting more, then reading more …. A self-perpetuating cycle. There are very few historians and very few China studies people in the field (and definitely very, very few Chinese historians), and the more I read from academics I respect – and other writers just doing smart stuff with games – the more I wanted to be part of it, too. There was a hole to fill, a China-shaped one, and I could be someone to help fill it. The more brilliant critical writing on games I saw, written by all sorts of people in the scattered little sphere that made up my sources, the more I wanted to be able to contribute to it, too. It’s one reason I’ve come back to writing, over two years after I stopped. It’s one reason I’ve been slowly picking up blogs I put down in December of 2008. I really liked being part of that ecosystem, I liked a lot of the people I “met,” and I really liked engaging with smart people with interesting ideas. I still do (so I’m back).

I certainly made great connections at UCSD thanks to Kotaku – e.g., I met my friend Stephen when, during the break for the first session of a seminar I was enrolled in and he was thinking of taking, I staggered outside to catch a breather. As the elevator doors were closing far too slowly for my liking, he came running down the hall, saying “Hey, hey! Are you Maggie Greene that writes for Kotaku?” I said that I was (now trying to keep the elevator doors open, to no avail), and he just said, “Keep up the good work!” I managed to squeak out a thanks as the elevator doors shuddered shut. Kotaku helped me meet a lot of interesting people on campus, which was and is great fun and good for me, intellectually and personally. It also really expanded the network of academics I knew beyond the bounds of UCSD, and at least writing for Kotaku gave me a little foot in the door. It had later (positive) ripple effects on my fledgling academic career as a “proper” Chinese historian. I think the sheer strangeness of that line on my otherwise standard history PhD student CV helped when it came to things like applying for dissertation fellowships – particularly when combined with proper “academic” work in the field of game studies, incredibly limited though mine is at this point.

I think it’s a little unfortunate I left Kotaku when I did; I’m in a much better position now to write about games than I was two or three years ago, when I was writing about games. But, part of the reason I am in a better position is because I did write for Kotaku – it was an essential part of developing that side of my academic and intellectual interests.

d. On a “legacy” (?): We are thinking

I stopped writing for Kotaku when I was 25. I’m 28 now. I find the mere idea of me having a legacy at this point pretty hilarious, but my name does still come up from time to time in conversations here or there, so I guess that means I did leave one. I certainly wasn’t thinking of leaving one, nor really sitting down and pondering my role in the vast universe of the blogosphere – well, not frequently and not terribly cogently, at least.

I didn’t start off wanting to be a game journalist. I still don’t want to be a game journalist. I wasn’t fulfilling any particular dream of mine to be a writer or anything else. People used to send emails and IMs saying “How can I break into writing about games?” I would think to myself, “Submit a writing sample based on Lu Xun and Chinese dresses to a young blog and see where it takes you? How should I know?” I just wanted to grow up to be a Chinese historian (and I still do – just one that happens to research games).

At the heart of my job, I was an aggregator. I didn’t write all the interesting things I posted about, I just had to find them, pull out a few quotes, write a few vaguely coherent sentences to bookend it (sometimes, not even that), and add a link. It was production, but of a particular kind. I knew that I wasn’t as smart, at least when it came to writing about games, as all the people I was linking to – I wasn’t producing the stuff, after all, just offering occasionally pithy commentary and sometimes clever titles. Furthermore, I was just one more writer, out of a long list of writers, that had passed through Kotaku (I mean, check the Wikipedia page if you doubt me here). I fell into the job by dumb luck, and I wasn’t any different than a lot of other people (except, perhaps, in having dismally low page views). It’s not like I built up a readership by the sweat of my own brow and laboriously worked to “CHANGE THINGS!”. I didn’t. I was just a writer on a Gawker Media blog, another cog in that big wheel.

But I did wind up doing something – I got a lot of things out to a much wider audience than they otherwise would’ve gotten. I tried to make sure that those wickedly smart writers with blogs that had awesome titles got out on a place like Kotaku, and those readers who maybe wouldn’t have found them – but were looking for that kind of thing – got a little nudge in the right direction. You know, just as I would’ve liked someone to do for me, if I’d been writing smart things about videogames, and like I wanted the big blogs to do for me before I discovered the intellectual underbelly of the blogosphere. Much as I’m writing this now (partially) to help someone else’s dissertation (well, that’s the intent, anyway), just as I wish Meng Chao could write for me. I’ve gotten a lot of help over the years, and I like to repay those favors when and if I can.

I guess one of my favorite examples of “what I was trying to do at Kotaku” was also one of my last. In late October or early November 2008, I got a really nice email from Daniel Martins Novais. Now, this was nothing out of the ordinary – the Kotaku inbox I had was a thing of terror, filled with press releases, tips on news items, and lots of people pitching their blogging or game to us. It was, in short, a giant headache with a few gems surrounded by a lot of dreck that was practically impossible to keep up with.

But Daniel approached this initial contact quite differently than most people (and quite wisely, though I don’t know if it was a calculated strategy on his part). Instead of saying ‘Here’s a game I made and would you please post it?’, he first wrote an email to me (just to me – not to the general ‘tips line’ that went to everyone, or to a bunch of us all CC’d together), explaining that he had really been influenced by Jason Rohrer’s work (which I had posted all of, up to that point), really wanted to do the game design thing full time, and would I mind just taking a look at the game he made, just to give feedback, because he really respected my opinion? No grubbing for a link or anything (of course, this made me more inclined to actually link to him if I liked the game).

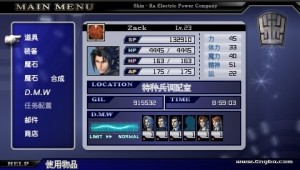

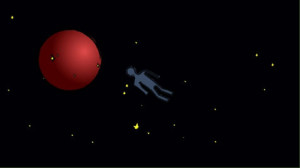

Screen from Estamos Pensando

I played the game, called Estamos Pensando (‘We are thinking,’ unfortunately no longer available). I saw the Rohrer connection. It was polished, sad, and sweet. I really liked it. So I posted it. It was one of the few times I remember posting something and watching it spread pretty quickly, since people actually gave my post credit. A slight diversion here, one that probably belongs in the section above. The issue of “attribution” in the blogosphere is a fascinating one (it occurs to me that it would probably make a great study from several angles – has someone already done one?), and one reason I really remember Estamos Pensando is because (thanks to “via” links) I could actually see where my work was going. With few exceptions, my impression of my work and its reach while I was doing it was confined to what I garnered from our stats page (listing page views, with me at the bottom of active writers – as always) and the occasional mention here or there.

I originally had one of my very favorite stories of making the acquaintance of someone in the game journalism world here, but in interests of not hurting said person’s feelings by appearing as though I’m poking unnecessary sticks at someone I’m really very fond of, I’ll just sum up the point: I took proper attribution really seriously and proper links, including the “via” part where warranted, were a matter of academic honor to me. I realize that probably sounds outrageously overblown (“It’s just a link,” right?), but bear with me. I once got “reminded” to give credit where credit was not due (on the assumption that it was due, an honest mistake), and it really, really offended me. It generally bothered me greatly to see how things wound their way around without leaving a trail that led back to the people who had discovered whatever article, and I was incensed that someone would try and say I was doing the thing that I so disliked. Lack of that little “via” seemed, somehow, pretty dishonest in a lot of cases. I tried really hard to make sure that I maintained my academic sensibilities where attribution was concerned.

Footnotes: I love them. LONG ones, too.

This was because, for me, a “via” link was the equivalent of a footnote, which of course I would not forget in a paper, since that would be plagiarism (and a fearsome, fearsome charge to have leveled at you). I’m not saying that not linking is the equivalent of plagiarism (though sometimes, it can skate damn close to the line – I ran into this with the “Atlanta Examiner,” whose writer seemed to do little more than repost everything I posted in a weekend without credit to me); but for me, it felt like it. I tried to treat fellow writers the same way I treated fellow historians, even if sometimes we were just aggregating and pointing back to the same original. It was also just a matter of habit from writing a lot of papers – I love doing footnotes (one of the great soothing joys for me when I write papers) so filling in my little “via” link in a proscribed format was something of the same ritual.

A great many sites never seemed to feel the need to give me credit, even when I damn well knew there was a 99.9% likelihood they had gotten the article from something I posted. I never sent emails or IMs saying, “Where’s my credit?” I wrote for Kotaku, a giant juggernaut of a site – why did I need credit? (at least, that’s what I assume people who didn’t give my work the courtesy of a blogger’s footnote were thinking). I wanted credit because I wasn’t a faceless automaton; I wanted to see where things I found wound up, too. I didn’t want other writers to feel the same way I sometimes did, so I was always careful to note where, if anywhere, I had procured a link from. I’m sure things slipped through the cracks on occasion, but I wanted that to be as rare as possible.

In any case, Estamos Pensando was one of the few times that I distinctly remember other blogs actually showing a clear trail to me, and it was delightful to see it spread – more so because Daniel was genuinely thrilled with the fact that I had posted the game at all, and the fact it was getting nice attention from multiple spots thanks to that first post I made was icing on the cake. It was just a post on a blog, but it made a difference – a good one – to someone. I felt really good about that. I still feel good about that. That sounds appallingly sappy – and I really don’t care.

That was a late, particularly obvious case, but one that I would like to think sums up what I was doing – consciously and not – at Kotaku. Giving a little more page space to a lot more things that shouldn’t have needed me, of all people, to be pushing them – but I somehow wound up with the platform and ability to do so. I suppose there were a lot of examples like that, but I guess because Estamos Pensando was the last big one, it’s one I most remember.

I hit my stride at some point and was comfortable with the fact that I would never be “popular”; there were people out there who liked what I posted, and got something out of it – something they wouldn’t necessarily have found on Kotaku otherwise. Sure, plenty of the audience thought I was a dull, pedantic, elitist snot (or me and my subject matter were just plain boring, or not why they came to Kotaku) – but I wasn’t writing for them. I was writing for me, and people like me. I wrote about the kinds of things I wanted to see on blogs like Kotaku, and apparently, other people did, too.

I did get to introduce people to neat sites and incredibly smart people and wonderful critical thinking on games. I hope I did facilitate in building networks between readers and writers and other readers and other writers (and I think I did, in some cases – maybe not all, but some). I at least wanted to show that there was a really interesting world of blogs that existed pretty apart from the “big guys,” and they were worth reading, too. Sure, there were other sites doing this, and probably doing it a lot better – reasonably widely read ones – but they didn’t have Kotaku’s readership.

I hardly had a captive audience, but I had a lot more potential readers to hook than most people. There were places to read about and talk about games in a really smart, intellectually engaged manner, if that’s what you wanted, and I wanted to point that out on the platform I had available to me. I wanted to post about things that I thought were important and didn’t get enough press in general. China, of course, would be the prime example – yes, I poked a lot of fun at silly press releases, but I also posted about “real” issues, and about a lot more than just laughing at crazy Chinese knockoffs. In retrospect, this was an incredibly smart thing for me to do for my own benefit, because I now have a whole body of work to look back on as I write papers years later. But from a less self-serving perspective, I did want to underline that there was more to gaming outside of the West & Japan than people dying after gaming binges and piracy. I think I wrote a longform essay on the very subject of getting outside mainstream news and thinking about games as a truly global product – precisely because I found the blinkered regional perspective terribly frustrating, as both a writer and consumer of gaming news and writing.

I was the least read writer on Kotaku, but it was a bigger audience than a lot of us will ever have. I had a funny conversation with one of my professors once, roughly the following:

“How many regular readers do you have, do you think?”

“Oh, I don’t know, not a lot – maybe 4,000 who regularly click on my stuff.”

“You realize that 4,000 would count as a book that sold well in our fields? And you have that every weekend, without thinking about it.”

I think about that sometimes, particularly when I’m up late at night and struggling with Historical Stuff that is frustrating me. I did have that. No, it’s not a monograph or a list of publications in prestigious journals, but it is something, regardless of whether many of my colleagues would think it important or not. I did make a difference, however little it may have been in the grand scheme of a blog like Kotaku (or the game blogosphere as a whole, or for game studies in the enthusiast press, or whatever). I managed to have a pretty impressive reach – not for a real, widely read blogger, but for an otherwise totally unimportant 20-something Chinese history grad student, even if it was something that was so far out of the purview of what “should” matter for my career that many people I respect highly never even gave it a thought. For most people in my “real life,” it was an odd curiosity and little more (“Maggie writes for a blog, huh. They pay people for that?”), but I had more of an audience at 24 and 25 than I will likely ever have again (and many academics never have), even for work that I try so hard at and put so much thought – and blood and tears and sweat – into. How to explain that? Sure, it was utterly pathetic compared to the reach my fellow writers had and have; but I think for many of us – a couple of hundred thousand page views a month is still quite the potential platform!

So I do try and remember that I did something once for a while that I was pretty good at (at least after a fashion; maybe not in the way I was “supposed” to be as a writer for Kotaku), and I did make some difference (I think), and people do still remember – even as I slog along at the moment, back to being a mostly anonymous, insignificant fish in the brilliant glittering sea of grad school and academia and my “real life.” It wasn’t always so, I remind myself, at least not in some areas of my life. And I’ll get there again someday, I hope, just in a different sort of way. I remind myself of all the wonderful things and people that flowed from that lucky, dumb chance I had – one that I’m very grateful for – and all those connections that are humming along as we speak.

I was a Kotaku writer once, and young ….

A screen from Rohrer's Passage, which got almost as many page views for me as "Goatgate" - not quite, but almost

Postscript: This was surprisingly hard to write. I meant to be a smart blogger and spread things out – and, since the person whose research made me sit down and write it in the first place is at GDC this week & I would assume has neither the time nor inclination to read this at the moment when there are so many more interesting and fun things going on than me pondering away incoherently, wait until GDC madness had subsided to publish it. I have the patience of a gnat and want feedback immediately (which is unrealistic at the best of times, more so when it’s GDC week & 70% of people I know on the internet are there and very busy!): Well, was it useful? What did you think? Did that change anything about the ways you’re thinking about my career? What else do you want to know? By the way, I think you’re missing X Y Z article of importance, and that one that you said was just a short blurb was actually …. However, it’s been sitting in my queue and I’ve been fretting over it, deleting this and adding that and fixing that grammatical flub or choice of words – and getting more and more upset, probably because it was cathartic to write, being the first (and last) time I’ve ever really written about that very important chunk of my life in any manner, and emotions are still bubbling up. So, in the interests of not having it lurking, begging me to fuss with it more, I’ve just gotten it up & not on the schedule I’d intended, so I can get back to other important things.

It all sounds so conceited, especially the last bit, I think (is it possible to ponder one’s “legacy” without sounding a little full of yourself? We’re supposed to leave that for other people to do, aren’t we?). But then, I’m more given to being hard on myself for everything I haven’t done, rather than being pleased with what I have done. Finding out that someone thought that my work was special enough to bother researching and writing about was a bit odd, then. I research and write about things myself; I don’t think any of us select topics that we find irrelevant or inconsequential, since that would just be pouring salt into the open wound that is writing a dissertation. So maybe it’s OK to be a little proud of what I did, whatever the sum of that is. I’m looking forward to reading an outside perspective on that part in my life, and how it fits in with bigger issues.

It feels good to have written it, and just as good that I won’t have to do it again. Unless, of course, Mr. Abraham has more specific questions he would appreciate my ruminations on – in which case, I will be happy to ruminate on specificities at a later date. I suspect having to dig around to remember the specifics would be more like research, and less like navel-gazing whining, and would probably not leave me with such a mournful feeling. Wang Xizhi, like so many of the old dead guys, spoke the truth – though the heart does give rise to longing, everything must come to an end.