As I mentioned in my general ramblings on our AAS roundtable, the general theme was “access.” Although Alan & Nick in particular focused on issues of accessibility in regards to sources (mostly for teaching), Amanda & I riffed on the theme of accessibility of sources (mostly for research). I spoke for a very short period of time – hoping, I think, that there would be more discussion in the comments period of some of the points raised regarding research (and there was a comment – tied, actually, to Nick’s discussion of the Japan Disaster Archive – about issues related to IP). As it turned on, the teaching portion was apparently of much greater interest to everyone, but I wanted to scribble down some thoughts beyond my short comments at the panel.

In speaking of access, I was specifically referring to the problem of getting into important, subscription-based repositories of digitized sources, databases like Duxiu, ChinaMAXX, China Academic Journals (CAJ), and the like. In some respects, this is the dullest manifestation of anything related to “the digital”: we’re talking about paper sources that have been scanned, OCR’d, and put up on subscription-based sites. We’re not talking world-changing, discipline-transforming use of technology here, are we?

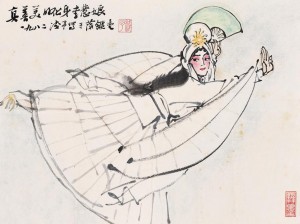

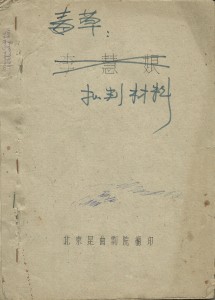

Not exactly, no, but you’d be surprised. During our research seminars in grad school (and at other points, of course), my advisors would occasionally comment on the changes the field had undergone since they did their research decades ago. The ability to do keyword searches of Chinese-language materials has changed the way we research – for one, it means that you (very easily) can find references in the most scattered of places. The example I usually point to is my discovery of a poem one of my playwrights, Meng Chao, published in Xin tiyu 新体育, the premier sports & physical culture magazine of the 1950s and 1960s. I’d been thinking of getting something going on Chinese mountaineering, but turning up this little gem while running a usual search (in hopes of turning up something from one of the theatre or literary journals) really made me sit up and take notice. Now, I did have a similar experience after I purchased a 1967 newspaper article on ghost opera off of the second hand book website, kongfz.com (I’ve written about the glories of online book shopping in China before). There, I noticed a strange line about a 1962 spoken language drama titled Mount Everest. But that was happenstance on a whole different level – the kind of thing that is tremendously difficult to replicate.

My advisors commented on the change – the ability to really drill down on a narrow set of terms or people and have hundreds or thousands of articles at your fingertips is quite different from spending ages paging through paper documents by hand, looking for scattered references. On the one hand, there’s a lot that can be gleaned from perusing hardcopy sources while you look for references here, there, and everywhere. On the other, databases can turn up references in the least likely of places – like Meng Chao in a magazine that I would never otherwise pick up while researching opera!

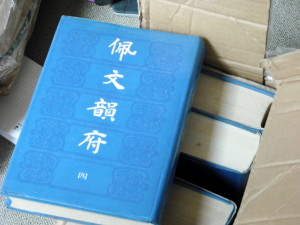

The accessibility of these databases, with enormous stores of documents, hasn’t lessened my reliance on hardcopies; for instance, I own a fairly complete run of Theatre Report æˆå‰§æŠ¥ for the years between 1955 and 1966. This is one of the primary sources for my work on opera reform & it was a fairly expensive (and space-consuming) thing to purchase. I did so because I like being able to browse hardcopies, and it is different from “browsing” digitized issues on CAJ, or doing specific keyword searches on Duxiu. I also own a lot of very minor regional drama publications from the 1950s, most of which don’t exist in libraries or digital archives. But there’s simply no denying that one reason I managed to cough up a dissertation that was reasonably solid is because I had the tools at my disposal to make wading through thousands and thousands of articles feasible. These tools are simply part of doing research these days – important parts of research.

And unfortunately, because I didn’t land at a school that has a large Asian studies program & the resources to devote to it, it’s access I’m scrambling to maintain after this year. Access that my work in large measure depends on. Before this gets taken out of context as a “poor me, I didn’t land a job at an Ivy” whine, let me say that I’m quite happy where I am, and this is problem that extends to what I suspect is most of us in this field (at least in the US). I realized that this was a bigger problem than I had first thought when a friend, who is installed at a very well-respected private institution (although one with – again – a relatively small body of Asianists) emailed to ask what I was doing about access; I was shocked that my friend’s school didn’t subscribe to these kinds of resources. So even places that look like they have more money to fling at research sources than my land grant institution often can’t justify it for a handful – if that – of faculty members.

My advisors may have commented on the way this changes how their grad students approached research topics, but no one is talking about how access – or not – to these sorts of materials are important for the field as a whole. Most of us don’t wind up at institutions with a large population of Asianists, and anyone in academia can speak to the trimming of budgets that make every penny really count. In today’s climate of reduced funding for libraries, and the fact that many more schools have at least one Asianist (if not more) on the faculty than was probably the case forty years ago, what happens to those of us outside the realm of a relative handful of institutions that can afford subscription services?

Here’s what I sort of feel like my field is telling me, mostly by not saying anything at all (that’s Duxiu, by the way, my most oft-used database):

This is a really, really important issue, and it’s something I feel like our (inter)national organization dedicated to Asian studies could actually facilitate discussion on – and maybe even solutions. Database companies are not set up to cater to individual scholars seeking access; they negotiate contracts with individual universities and consortiums (many UC campuses, for instance, buy in to online resources together). Some companies, like East View (which handles CAJ and other Chinese materials, as well as databases of Russian & Arabic sources), specifically request you go through your libraries – and based on their pricing structure, my university would fall into the same category as, say, Harvard or Berkeley (which certainly have a lot more Asianists than we do!). I am definitely exploring my options, including getting in contact with institutions that have (in theory) service to neighboring areas like Montana as part of their mission. But wouldn’t it be nice if people – including independent scholars, and people in more populated areas – had an easy way to buy in to subscription services?

In my presentation, I mentioned the German system, which is brilliant, wonderful, and inclusive. Individuals – and institutions – can subscribe to CrossAsia, which provides access to a wide variety of subscription services. All an individual needs is a Berlin Staatsbibliothek card (which is acquired for a very reasonable yearly fee); those affiliated with institutions can get access in that way. Over dinner, Hilde explained a little more about how CrossAsia came into being – basically, an individual librarian marshaled the entire effort and managed to pull all German universities into the system. For small outposts, it actually made it affordable to get their Asianists access to a huge number of databases. For much bigger programs, it wound up being cheaper for them to both maintain access to the things they already subscribed to, and gain access to new resources. Put into American terms, it’s a system that made sense for the Montana States or Mary Washingtons of the world and the Harvards and UC systems.

It would be delightful if this could be replicated nationally, but the US isn’t Germany. Still, I can’t help but feel there’s more we collectively could do as a field to make inroads in ensuring access to vital resources. I chatted with a colleague after this panel, and mentioned the access issue – he said that it was funny (though not surprising) that a lot of the promise of digitization & popularization, etc. has wound up reinforcing old elitist boundaries (this is someone who left one of those Old Elite Schools to come to a land grant institution, so it’s not bitterness on his part). No institution could afford to replicate today the kinds of collections found in the bastions of area studies – not even the bastions, as the price of (print) sources is simply astronomical in many cases. And yet, very often, access to these things which should help spread the wealth around a little more is still limited to places that can afford to cough up very expensive yearly fees, negotiated by individual institutions. It’s just gatekeeping of a different manner.

I’m not asking to simply leech off schools with better endowed libraries than my own, for free; I would cheerfully pay my own money – far more than the cost of a Berlin Staatsbibliothek card – every year to ensure I had access to materials to continue doing my research with a minimum of muss and fuss. At the same time, I am not in a position to negotiate as an individual with CAJ, with Duxiu, with the People’s Daily database. If the German case proves anything, it’s that not just smaller institutions won by coming together in a consortium: even the big, elite Asian studies institutions got something out of the deal (the same thing smaller institutions got, actually: more & better access, cheaper). The more people – or institutions – you have bargaining with database companies (who really have a lot leverage in this situation, just as companies like JSTOR have in providing access to academic journals), the better.

Bigger programs are already subsidizing my research, to some extent – every time I order materials on inter-library loan (things like microfilm – the type of sources that are often available, at least for my period, online through databases), that costs everyone money: my library, their library. Does ILL really make more sense than providing some kind of buy-in to subscription services for a reasonable fee? I’m not a librarian – and don’t know the economics of everything – but I think we need to at least start having a conversation (between academics, librarians, and database companies) about how we could all work together. Both the elite institutions, and those of us who have left the elite nest at the conclusion of our graduate training.

I’ve been encouraged to talk to our library about subscribing to at least one critical database, and I’ll probably broach the subject with our librarians (and see what suggestions they have). But truthfully, I am at a land grant institution, one without massive resources or a wonderful Asian studies collection. I’m a lot more interested in making sure my students have access to books, so I can stop lending out my personal copies of tomes I consider basic acquisitions for an academic library. The thousands and thousands of dollars a year it would cost to negotiate access that would benefit only me are, in my opinion, better spent on acquisitions that would benefit a lot more people.

I’m not ashamed for holding a TT position at a school without a history of being a hotbed of Asianists. Really, that describes most of us – few of us will wind up at institutions that look like the universities where we trained as grad students. Even a relatively lateral move – say, from one UC to another – is not going to mean a total equivalency in regards to resources (for one thing, different schools – even the bastions – have different emphases in their collections). Isn’t this the kind of discussion we should be having? The debate over open access to academic publications acknowledges that databases are a relatively new, very important issue – and access to those resources is incredibly important. The accessibility of primary source databases should be part of that discussion. And, just like bigger conversations on teaching and research, this is something that I want my field to be participating in. Keeping an eye on AHA discussions is great, but there are some specific issues here that we need to be discussing, not just skirting the edges of in broader, discipline-wide conversations.

Things have changed a lot since my advisors did their training. I just hope that it doesn’t take another forty years for us to collectively figure out how to manage the changing landscape of the past ten.