Academia is funny business: I’m sure there must be other jobs that train you for a relatively long period of time & then dump you out for your actual training after you’ve secured employment, but I can’t think of any. My first semester as a real, live professor was fascinating and frustrating and wonderful and awful – all things wrapped up in one. I was fervently thankful for winding up at a nice university, in a nice department, with nice students, and nice colleagues. But I woke up many mornings feeling pretty terrible about my teaching ability, my ability to put competent syllabi together, my ability to get other stuff done in addition to teaching a big(ish) lower division survey course & an upper division course, and so on and so forth. I had a few meltdowns (though fewer than I would’ve expected, truthfully). As a colleague said to me, it’s a terribly demoralizing thing to get up in the morning and feel like you suck at your job; on the other hand, it’s not like we get any training in this stuff.

Academia is funny business: I’m sure there must be other jobs that train you for a relatively long period of time & then dump you out for your actual training after you’ve secured employment, but I can’t think of any. My first semester as a real, live professor was fascinating and frustrating and wonderful and awful – all things wrapped up in one. I was fervently thankful for winding up at a nice university, in a nice department, with nice students, and nice colleagues. But I woke up many mornings feeling pretty terrible about my teaching ability, my ability to put competent syllabi together, my ability to get other stuff done in addition to teaching a big(ish) lower division survey course & an upper division course, and so on and so forth. I had a few meltdowns (though fewer than I would’ve expected, truthfully). As a colleague said to me, it’s a terribly demoralizing thing to get up in the morning and feel like you suck at your job; on the other hand, it’s not like we get any training in this stuff.

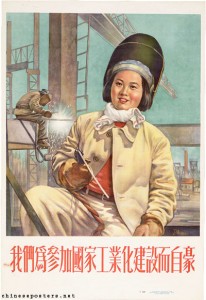

In any case, it was a learning experience & certainly wasn’t the disaster it could have been, but it’s been with no small relief that I’ve discovered I am (sort of) getting my teaching legs. A few years ago, I had the opportunity to teach a course on “women and the Chinese revolution” at UCSD, which I taught in the way I thought it was supposed to be taught. What I discovered is that when you start in the late 19th century, it is (or it is for me) very hard to get students over the May 4th hurdle: there’s a certain narrative about Chinese women “before,” and a narrative “after,” and despite trying to illustrate the problems of – or reasons for – a particular narrative of “before,” it’s hard to do without showing. So I had a somewhat wild and crazy idea, when I decided my second semester of teaching would include teaching “Gender and East Asia,” to scrap the 20th century focus & go back: way, way back, and pull out the things that have been so compelling for me. I thought (and still think) if I could just underscore some aspects – really show them, let them read these wonderful things I love so much! – my students would come away with a better appreciation for the lives of women prior to their miraculous “emancipation” in the 20th century. Time will tell if this approach will work (the syllabus needs a lot of tweaking, as they always do), but it’s been a lot of fun seeing how students respond to these documents I love so well.

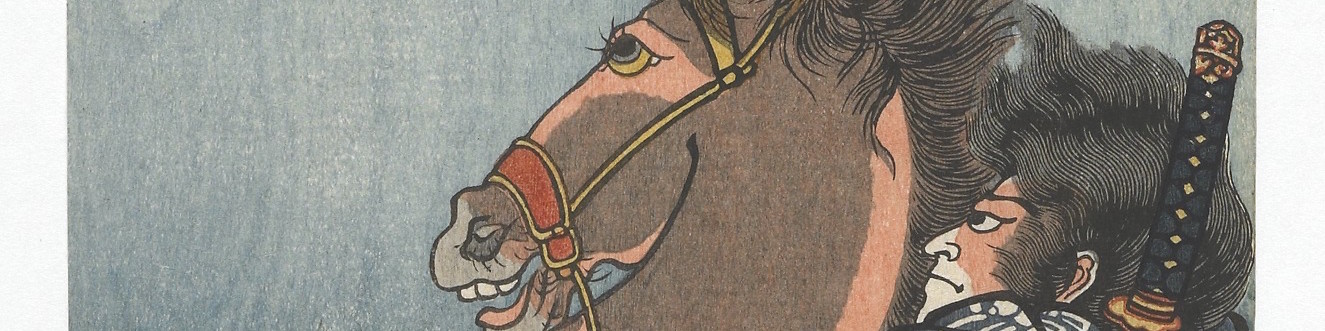

I am not a historian of gender. In my own research, I deal largely with male intellectuals (I think the only female voices – besides the “voices” of ghosts written by men – are the odd essayist or artist), and though I’m dealing with a topic that has been examined through the lens of gender with great success (Judith Zeitlin’s amazing The Phantom Heroine: Ghosts and Gender in Seventeenth-Century Chinese Literature), it’s not a dimension I explore in any systemic manner. I think there’s something about the fantasy of ghostly women that I need to explore further – and hopefully will in my monograph! – but I would never claim to be part, or even really want to be part, of the amazing circle of people working on gender history in China.

At the same time, surveying my own career, my interest in Chinese history was largely sparked (and later nurtured) by both secondary works of gender history, and primary sources dealing with “the question of woman” in the 20th century, Ming-Qing women poets, and those pesky ghosts. Would I be a Chinese historian were it not for Xu Can å¾ç‡¦ or Dorothy Ko, Lu Xun’s “What Happens After Nora Leaves Home?” or Susan Mann? Probably not. Even my first literary love in East Asia – way back in high school – was Sei Shonagon’s Pillow Book. So it’s something of a pleasure to introduce to students – many of whom have no experience with this stuff – to things I love so very much. But I can find it inordinately frustrating, mostly due to my inability to package all of it as well as my professors did. I would like to think that my enthusiasm shines through & helps with some of that, but I am never so unsure of myself as when I am completely unable to stimulate discussion on a short story of Lu Xun’s, for example (this has been a bugaboo of mine since my very first time in front of an undergraduate class; I despair of my ability to ever do it well). The closer you are to something, the more you desperately want to get across “the purpose,” why it’s important, the meaning – you want to show why it’s something you love so much (or I do, at least). I realized it’s one reason I’ve been a bit frantic about the idea of revising my dissertation: I really care about these intellectuals, Meng Chao in particular, and he deserves a better biographer than me. Because if his story is going to be told in English for once, it needs to be good. He deserves it. I’m afraid of not being able to do him – and his beautiful ghost – justice; the prospect seems worse than not writing it at all.

I’ve had an up and down week here, one where I’ve felt like a horrible teacher, a horrible researcher, a horrible colleague, a horrible human being, for no discernible reason (I suspect part of it is the long winter here grating on me a bit, and just general exhaustion that often hits in the middle of the semester). I’m terribly homesick for some place that’s never existed (namely, somewhere my favorite people all are, neatly collected for me), a bit lonely, and fretting about my dissertation, a fresh wound into which I continue to pour salt in a very masochistic manner. So – in between getting work done and panicking about my life – I’ve returned to old friends, most of whom I didn’t have time to introduce my students to. It’s a good reminder of why I do this stuff, even if I don’t “do” women’s writing culture in imperial China. A reminder that I’m lucky to be here, and very lucky to have the flexibility to teach topics in ways that resonate with me; a reminder that I’m probably not as terrible at conveying much of this as I think I am, as I know my affection for these long-dead authors and their lives must shine through.

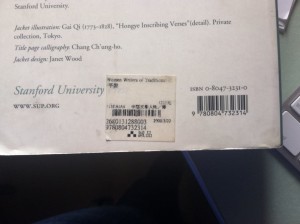

Much like listening to my beloved lute music, it’s hard not to be melancholy when reading many of my favorite poets in English or in Chinese – but it often makes me feel better. It’s partially the subject, partially the fact that I have memories attached to my books, when I first read so-and-so, first learned of such-and-such. First taught this, that, or the other. I gave a colleague one of my favorite monographs (Andre Schmid’s Korea Between Empires) last week & my heart nearly broke when I pulled it off the shelf – it’s been a long time since I last read it, but it’s battered and tea stained, having been carried in my purse when it was new (along with a not-totally-empty travel mug) for several weeks. And all that seems like so long ago (and it was!). My big poetry anthology was purchased at Eslite in Taipei years ago, for the princely sum of 1225NT (around $40 – not a bad price for an enormous, wonderful book); every time I pick it up, a lot of memories come rushing back. It’s dog-eared and battered (my love of a volume can usually be discerned by its degree of dog-earedness; also on how many coffee or tea stains it has on its edges), but I still occasionally put my nose in it and inhale deeply. It represents a lot of stuff that no longer exists. So maybe that’s one reason I get anxious about teaching this stuff; I feel like I’m teaching part of me (and, as I often remind my students, histories often reflect more on the present than they do on the past they purport to represent; surely the same extends to teaching). I don’t know that I’m doing these women justice, but I’m trying, and surely that counts for something.

“Shuilong yin: Matching Su’an’s Rhymes, Moved by the Past” (Xu Can, trans. Charles Kwong, from the Women Writers of Traditional China)

Under the silk tree’s flowers we lingered;

Then, I once tried to explain to you:

Joy and sorrow turn in the blink of an eye,

Flowers, too, are like a dream –

How can they bloom forever?

Now indeed

The terrace is empty, the blossoms are gone,

Leaving weeds enwrapped in sprawling mist.

I recall the time of splendid sights,

The time of bustling glamour,

Each seizing on the spring breeze to show its charm.

Sigh not that the flower-spirit has gone afar;

There are fragrant flower poems inscribed on floral paper.

Here, pink blossoms open and close,

Green shade hangs dense and sparse,

Greeting us as though with a smile.

Holding a cup, we may chant softly,

As if our old companions

Have returned in our dream.

From now on,

Candle in hand, let us admire the flowers;

Never wait till the flower sprigs have grown old.

For my nineteenth birthday, I bought myself a PlayStation 2 and a copy of Final Fantasy X. It was something of an impulse purchase, but I passed a nice week afterwards holed up on my first real gaming binge. While I’d played through the Final Fantasy offerings for PS1, FFX was the first of the series to really catch me, and it’s part of the reason I’m generally playing some JRPG or another, or nothing at all.

For my nineteenth birthday, I bought myself a PlayStation 2 and a copy of Final Fantasy X. It was something of an impulse purchase, but I passed a nice week afterwards holed up on my first real gaming binge. While I’d played through the Final Fantasy offerings for PS1, FFX was the first of the series to really catch me, and it’s part of the reason I’m generally playing some JRPG or another, or nothing at all.