Six years ago – give or take a week or two, I can’t remember when the semester started – I found one of the great intellectual loves of my life. I suppose I often think of the real birth of my research life as being tied to my actual birthday: it was at some point around the time I turned 26 that I discovered someone who would have been, had he been living, 107. A bit of an age gap, then.

My grad program was structured in a very clear way, so that during coursework, you knew exactly what was going to be on your plate: a historiography seminar in the fall, then a two-quarter research seminar. In the winter quarter, we researched (including our famous “Bataan Death Research March” to the Bay Area to hit Stanford & Berkeley – trial by fire, and what I suspect was partially designed as a real bonding experience. You get to know your classmates on a whole new level when you’re going through 10 hour days in a library after catching a 6 AM flight). In the spring, we wrote, with the final product being a journal-length essay that was hopefully up to standards for good journals in our field (indeed, many of us published at least one of our essays; some published all of them!).

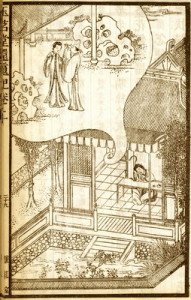

I was panicked my first year & selected what turned out to be a difficult subject, compounded by my general incompetence. I decided that for my second year, I was going to research something that I knew made me happy: The Peony Pavilion (Mudan ting 牡丹äº), one of the most famous of the “marvelous tales,” a big sweeping epic of a ghost play. It has undergone quite the revival in the past 15 or 20 years: how did it get to that point, I wondered?

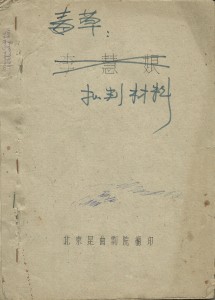

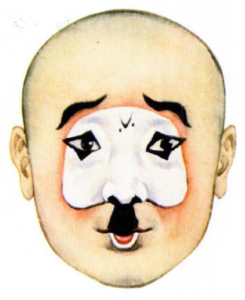

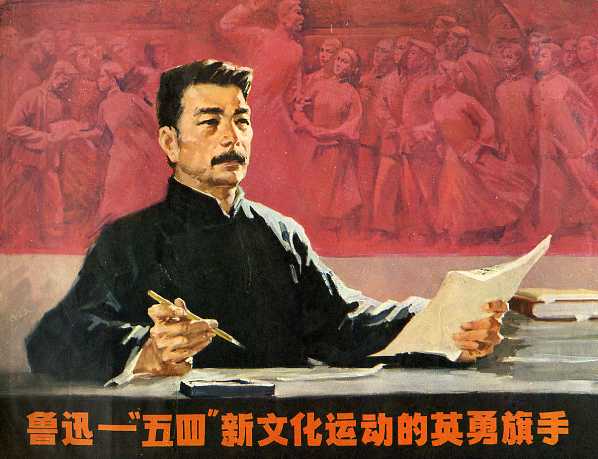

As it turned out, it really was in need of revival – I was doing some preliminary work with Chinese theatre yearbooks (nianjian 年鉴), which include all sorts of statistics on plays performed by troupes and so on. Peony was basically nowhere to be found; I knew enough to know this would be a very tall order to research, and I needed to find some other angle. In desperation, I brought a typed up spreadsheet – listing years, troupes, plays performed – I had made to the wonderful professor who helped us once a week with our documents. “Can you just look at this really quickly and tell me if something pops out? I just don’t recognize most of these plays.” She immediately hit upon one and asked “What is this doing here?” I looked, and said it had apparently been a very popular play in the early 1980s. “Do you know about this one? It’s also a guixi [鬼æˆ, ghost play], but it was criticized during the Cultural Revolution – like Hai Rui [Wu Han’s Hai Rui Dismissed from Office, Hai Rui baguan 海瑞罢官].” She told me she remembered seeing big character posters in Beijing as a girl, criticizing the play and the author. How interesting, then, that it was so popular in the early 1980s.

I had never heard of it, or the author. And sure enough, when I trotted off that day to do a quick search of the literature, barely anything turned up. Rudolf Wagner, whose The Chinese Historical Drama remains a more or less unparalleled study of the “new historical play,” a quarter century after its publication, had this to say:

Among Western scholars, considerable attention has been given to Wu Han’s play, much less to Tian Han’s, and very little to Meng Chao’s. (80)

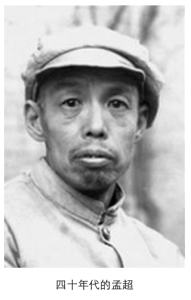

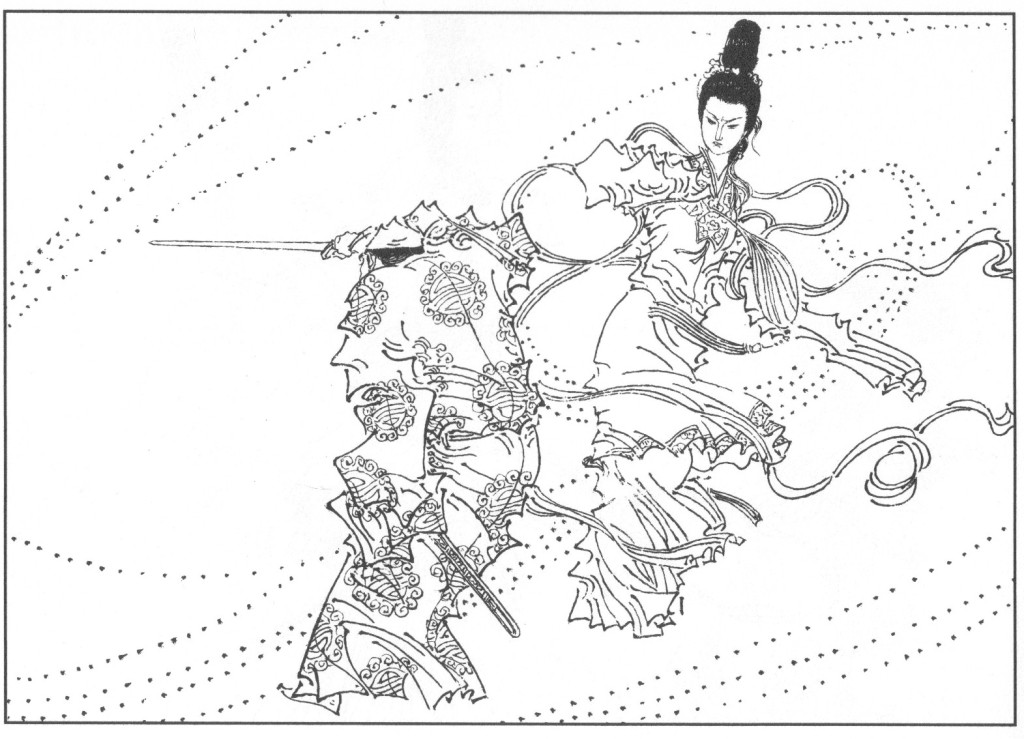

Indeed, as I noted with no small bit of wonder a little later, so little attention had been given to Meng Chao’s play that this Kun opera (kunqu 昆曲) was consistently misidentified as Peking opera (jingju 京剧). I’d discovered something - Li Huiniang – and someone – Meng Chao – and that has more or less driven my fledgling career since, even as the topic has spiraled outwards and sucked in more and more angles and more and more people and more and more stuff, as projects are wont to do. I always come back to him and his ghost – it’s hard not to, given the subject of my work, but partially because I have spent so much time with “him” (rather, the literary detritus of his life). When I’m having trouble writing, I will often turn to the parts of my manuscript that deal with him – a story I know so well, and something that can often get me over a case of writer’s block.

Over the years, I’ve collected bits and pieces of his life – I look a bit longingly at a book I otherwise wouldn’t want on the site Kongfz, which has an inscription he wrote (having Meng Chao’s writing in his own hand on my bookshelf!! I can only imagine). I’ve come to know him through his own writing, but mostly the writing of others; they flesh out the erudite, but distant, man who appears to me otherwise. An exception is reading his early zawen (sharp, satirical essays) published in the early ’40s (admittedly, he was around 40 at the time, so not quite young); I was warmed to read him discussing his work habits, his custom of working mostly at night. A friend recalled he always seemed to be running everywhere in the early 1940s, in Guilin; he had no trouble writing, and could write a zawen without thinking of it. He was also a poet. He later wrote elegant, dense prose. He – like so many of that generation of Chinese intellectuals – seems, at least from this distance, to inhabit (somewhat comfortably) strange territory between great classical traditions and new Marxist ones.

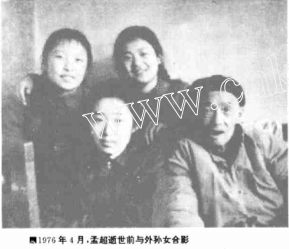

He’s not handsome, not even when comparing him to the two other men his name is indelibly linked with. In his Republican-era photograph (which, admittedly, came when he was already middle age: perhaps a younger Meng Chao would be a handsomer Meng Chao), he has neither the round-faced, amenable look of Wu Han, nor the lean, dapper appearance of Tian Han. Any idealization of him I have in my head is not because I’ve been presented with a fine specimen of manhood; it’s his literary acumen I find so appealing. It’s hard to find photographs of him; I have seen only three. One – my favorite, even in the higher resolution version that makes him look older and more bewildered (it reminds me that this man had been through a lot by that age, impressive family background or no!) – shows him as a man in his late 30s or early 40s, with a face a bit like a basset hound. He looks very earnest. The next was taken sometime in the 1950s, and is a typical cadre photograph – large glasses (ridiculously so, from the vantage point of 2014), much older than the first. The last is the saddest, and shows a very old man with a daughter and two granddaughters. He looks much, much older than his 73 or 74 years. That one was taken very late in his life, after over a decade of persecution and campaigns, after being branded a niugui-sheshen 牛鬼蛇神, an ox ghost-snake spirit. There’s no trace of that earnest young man in the Republican-era photograph. What would that old man say to the young figure, I wonder?

One of the most important commandments as a historian is “Do no violence to your sources”; treat them carefully, analyze them thoughtfully, be aware of what you are bringing to your interpretation. It seems that much more important when dealing with a life, especially a life that has been so little looked at in comparison to his peers. Knitting together these disparate pieces of a literary life makes me nervous, and I wonder sometime if I’m too likely to sympathize with men like Meng Chao (after all, Li Huiniang or not, he was part of The System that took root; surely he – and his compatriots – shoulder some of the burden for the disasters that came later, even if they themselves were swept up in them?). But he’s a very human actor to me, one that reminds me that all these other names and people (and scores of anonymous people besides) were people, and these were lives, and ultimately that’s the important part of the story – not abstract ideology or theory. One of my favorite pieces I ever wrote was for The Appendix, called The Woman in Green – the story of Li Huiniang, from 1981 all the way back to 1381. I loved writing it because I got to imagine, on a scale that I can’t when writing purely academic work, scenes from a life I’ve written again and again.

One of the most important commandments as a historian is “Do no violence to your sources”; treat them carefully, analyze them thoughtfully, be aware of what you are bringing to your interpretation. It seems that much more important when dealing with a life, especially a life that has been so little looked at in comparison to his peers. Knitting together these disparate pieces of a literary life makes me nervous, and I wonder sometime if I’m too likely to sympathize with men like Meng Chao (after all, Li Huiniang or not, he was part of The System that took root; surely he – and his compatriots – shoulder some of the burden for the disasters that came later, even if they themselves were swept up in them?). But he’s a very human actor to me, one that reminds me that all these other names and people (and scores of anonymous people besides) were people, and these were lives, and ultimately that’s the important part of the story – not abstract ideology or theory. One of my favorite pieces I ever wrote was for The Appendix, called The Woman in Green – the story of Li Huiniang, from 1981 all the way back to 1381. I loved writing it because I got to imagine, on a scale that I can’t when writing purely academic work, scenes from a life I’ve written again and again.

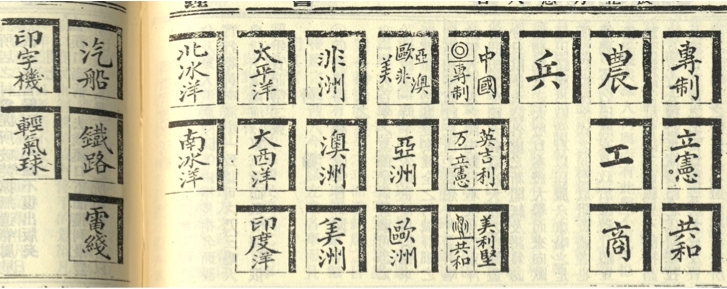

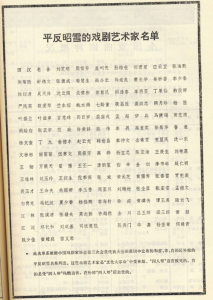

He reminds me, while teaching, to impress that fact on students: that these were once living, breathing humans – not just names or faceless individuals.  I show my students a page from a theatre yearbook announcing the rehabilitation of opera people in the late 1970s (lists like this were published all over the place), and I talk them through the jumble of (to them) unintelligible characters – representations of lives lived, good and bad. Here, a luminary who died in prison; there, a star who was beaten to death by a gang of overzealous teenagers; sprinkled throughout, people who committed suicide, fearing what would happen if they didn’t. And there (in two little characters; ones that I recognize the shape of no matter how small the image I’m looking at), a man who died in a Beijing hutong, his family suffering from being attached to someone who produced a so-called fandang fanshehuizhuyi åå…šå社会主义 - anti-party, anti-socialist thought – poisonous weed; broken, old, sad, and bitter. They’re simply recognizable names, poster children for all those other lives lived (and ended) in much greater anonymity. But human, concrete: not just names.

He reminds me, while teaching, to impress that fact on students: that these were once living, breathing humans – not just names or faceless individuals.  I show my students a page from a theatre yearbook announcing the rehabilitation of opera people in the late 1970s (lists like this were published all over the place), and I talk them through the jumble of (to them) unintelligible characters – representations of lives lived, good and bad. Here, a luminary who died in prison; there, a star who was beaten to death by a gang of overzealous teenagers; sprinkled throughout, people who committed suicide, fearing what would happen if they didn’t. And there (in two little characters; ones that I recognize the shape of no matter how small the image I’m looking at), a man who died in a Beijing hutong, his family suffering from being attached to someone who produced a so-called fandang fanshehuizhuyi åå…šå社会主义 - anti-party, anti-socialist thought – poisonous weed; broken, old, sad, and bitter. They’re simply recognizable names, poster children for all those other lives lived (and ended) in much greater anonymity. But human, concrete: not just names.

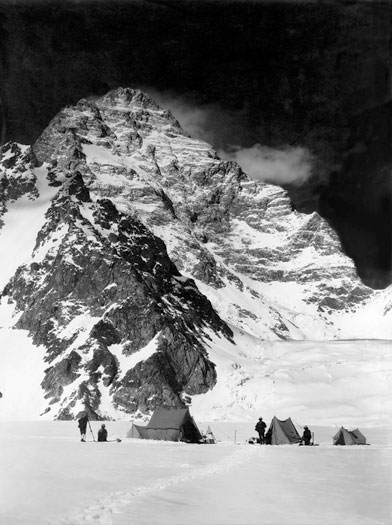

I am not so cocky as to think I’ve done some great, field-changing service by highlighting the life of this elite (but run of the mill elite!) intellectual, though I do think his story adds something to our understanding of the time that simply highlighting stars like Tian Han and Wu Han doesn’t. Â But at the same time, there’s something nice about having a person to attach yourself to. He’s “my” Meng Chao, an anchor for many other things. He’s even turned my attention to subjects far beyond the bounds of opera (the 1960 conquest of Mt. Everest, for instance!). I worry often that I’m not going to be able to do him justice, but wanting to do him and his story justice is a constantly driving force. Â I am doing my best for a man I’ll never meet.

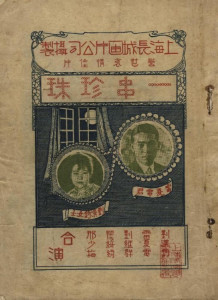

odds); it’s actually quite an important thing in Chinese literature, including some of the greatest things ever written in any language.  The English translation doesn’t convey the cultural significance of roundness (as Zhang Zhen notes in An Amorous History of the Silver Screen: Shanghai Cinema, 1896-1937, the significance of datuanyuan goes way beyond a cliché, and points to a kind of cultural conditioning – she mentions, for instance, the importance of visual cues like the typical round table used for family meals, as well as cosmological symbols like the full moon, in early Chinese cinema that had a tendency to rely on the “big reunion” as a plot structure). Cultural resonance or not, forcing a datuanyuan sometimes leads to bizarre results, like in the 1926 film A String of Pearls (Yi chuan zhenzhu 一串çç ), based loosely (and I do mean “loosely”) on the famous Guy de Maupassant short story “La parure” (The necklace), where the emotional punch of the story is more or less removed by an effort to ensure the happy ending. I suppose this is one complaint with happy endings in games; they can seem contrived or leave massive plot holes.

odds); it’s actually quite an important thing in Chinese literature, including some of the greatest things ever written in any language.  The English translation doesn’t convey the cultural significance of roundness (as Zhang Zhen notes in An Amorous History of the Silver Screen: Shanghai Cinema, 1896-1937, the significance of datuanyuan goes way beyond a cliché, and points to a kind of cultural conditioning – she mentions, for instance, the importance of visual cues like the typical round table used for family meals, as well as cosmological symbols like the full moon, in early Chinese cinema that had a tendency to rely on the “big reunion” as a plot structure). Cultural resonance or not, forcing a datuanyuan sometimes leads to bizarre results, like in the 1926 film A String of Pearls (Yi chuan zhenzhu 一串çç ), based loosely (and I do mean “loosely”) on the famous Guy de Maupassant short story “La parure” (The necklace), where the emotional punch of the story is more or less removed by an effort to ensure the happy ending. I suppose this is one complaint with happy endings in games; they can seem contrived or leave massive plot holes. This is much harder to do in literature, for obvious reasons, although a single work can encompass all those moments. In drama, this is helped by the fact that the sprawling Ming tales were not performed in their entirety, and were instead seen in excerpts. Some of the most enduring parts of Tang Xianzu’s 汤显祖 masterwork The Peony Pavilion (Mudan ting 牡丹äº), or at least the ones that get trotted out the most, are not, in fact, the end, where everything works out – they are the beautiful and rather tragic (or at least bittersweet) early scenes. Considering the fears of moralists that chuanqi like Peony would drive women to madness, suicide, or worse, it seems that even having a happy ending was no guarantee your audience would gravitate towards that! Instead, portions of the reading audience seemed to fixate on the somewhat depressing (perhaps more realistic?) chapters – an acknowledgement that the datuanyuan was simply a fantasy, impossible in real life? The famous “Walking through the garden, waking from the dream” [Youyuan jingmeng 游å›æƒŠæ¢¦] section is rather wondrous – and it does feature quite the fantastic dream! – yet it’s simply that: a dream. And yet the (male) authors seemed to love writing the fantastical ending, no matter how improbable, even if those weren’t the parts segments of their audience gravitated towards. Perhaps this is partially a difference in producing and consuming; I wonder if fan-produced writing and art geared towards alternative paths or endings, fleshing out what happened after, writing a “perfect” scenario, whatever that might mean for an individual, often focuses more on the perhaps improbable yet perfect because it’s created largely to entertain one’s self and not really for an audience (publishing on fandom specific sites and the like notwithstanding) – not unlike some of the great fiction and drama in China.

This is much harder to do in literature, for obvious reasons, although a single work can encompass all those moments. In drama, this is helped by the fact that the sprawling Ming tales were not performed in their entirety, and were instead seen in excerpts. Some of the most enduring parts of Tang Xianzu’s 汤显祖 masterwork The Peony Pavilion (Mudan ting 牡丹äº), or at least the ones that get trotted out the most, are not, in fact, the end, where everything works out – they are the beautiful and rather tragic (or at least bittersweet) early scenes. Considering the fears of moralists that chuanqi like Peony would drive women to madness, suicide, or worse, it seems that even having a happy ending was no guarantee your audience would gravitate towards that! Instead, portions of the reading audience seemed to fixate on the somewhat depressing (perhaps more realistic?) chapters – an acknowledgement that the datuanyuan was simply a fantasy, impossible in real life? The famous “Walking through the garden, waking from the dream” [Youyuan jingmeng 游å›æƒŠæ¢¦] section is rather wondrous – and it does feature quite the fantastic dream! – yet it’s simply that: a dream. And yet the (male) authors seemed to love writing the fantastical ending, no matter how improbable, even if those weren’t the parts segments of their audience gravitated towards. Perhaps this is partially a difference in producing and consuming; I wonder if fan-produced writing and art geared towards alternative paths or endings, fleshing out what happened after, writing a “perfect” scenario, whatever that might mean for an individual, often focuses more on the perhaps improbable yet perfect because it’s created largely to entertain one’s self and not really for an audience (publishing on fandom specific sites and the like notwithstanding) – not unlike some of the great fiction and drama in China.

Well, theÂ

Well, the

For my nineteenth birthday, I bought myself a PlayStation 2 and a copy of Final Fantasy X. It was something of an impulse purchase, but I passed a nice week afterwards holed up on my first real gaming binge. While I’d played through the Final Fantasy offerings for PS1, FFX was the first of the series to really catch me, and it’s part of the reason I’m generally playing some JRPG or another, or nothing at all.

For my nineteenth birthday, I bought myself a PlayStation 2 and a copy of Final Fantasy X. It was something of an impulse purchase, but I passed a nice week afterwards holed up on my first real gaming binge. While I’d played through the Final Fantasy offerings for PS1, FFX was the first of the series to really catch me, and it’s part of the reason I’m generally playing some JRPG or another, or nothing at all.