(This is not a theoretically informed ramble; just a few thoughts on doing translation from the trenches) Despite my last post bemoaning the Peiwen yunfu (which I have a slightly better handle on now – but it’s still awfully scary for a dictionary!), I am enjoying my first formal foray back into translation in a very, very long time. Â My education in Chinese at the ICLP took a really different shape than my previous studies of French, Latin, and ancient Greek (Latin & Greek particularly). Â In the latter two cases, we spent most of our time translating – if not putting pen to paper, at least verbally going from Latin or Greek to English. Â In contrast, at the ICLP, we functioned entirely in Chinese – even in our classical Chinese courses, our “translations” of Warring States classics and poetry were from wenyanwen to modern, spoken Chinese (baihua). Â Yes, it was definitely translation of a sort, but going from one language I didn’t have a great grasp on to another language I still didn’t have a great grasp on was quite a different exercise from rendering Horace, say, into my mother tongue.

Even as a historian working with Chinese documents, I rarely sit down and translate a whole document. Â I read it in Chinese, mark it up, take notes, pull out a few quotes while I’m putting a paper together and translate those select bits and pieces. Â We get warned against falling into the “translation trap”: expending a lot of energy translating things we’ll never wind up using. Â So, while I’ve sat down and translated whole things here and there (short poems, slightly longer lyric poems, and so forth), I never had the sort of education on translating that I got in other languages. Â Digging into Meng Chengshun, then, is a crash course in translating a whole text from Chinese into English.

Still, I like translation a lot. Â I’m still learning the ropes of it in Chinese – and I have a great many things to learn – but it can be quite soothing. Â I like figuring out how words and phrases fit together, and how best to render them into English. Â I have always been more talented at poetry than prose – I shocked more than one Latin teacher (actually, every Latin teacher or professor I ever had) with my total incompetence with finer points of grammar, while still being able to flit through all kinds of different poems with relative ease (the grammatical incompetence came back to bite me in the ass when we hit more difficult prose; Suetonius felled me). Â I always took a pretty hippy-dippy stance on it: poetry generally requires opening your mind and letting yourself slip into it and tease out the complexities, it can’t be manhandled with grammar and logic. Â Silly? Â Maybe, but I still think that’s the case.

Taking anything from one language and putting it into another can be difficult.  Chinese is a very difficult language to begin with (at least, in a lot of respects), and a very self-referential one, which makes translating that much more difficult.  Especially when one is just learning your way around the whole business of translating.  My translation – about 3/4 of the way done – has as many footnotes as many of my papers do.  “Do I say ‘Bo Juyi’ [a famous poet] or ‘Jiangzhou’s Sima’ [his sobriquet in the text]?” – and that’s an easy one.  I’m translating for a specific, not-necessarily-specialist audience in mind; considering this translation’s hopeful future use, I can’t simply assume that everyone know who the “banished immortal” is (that would be Li Bai).

It seems that almost every poetic allusion has its own history that stretches back hundreds of years or even longer – is it my job as a translator to put a monster footnote every time one of these appears?  Or just for the particularly abstract?  Can we just let the poetic allusions stay as pretty phrases, if it’s not critical to understanding the play if you’re missing a reference to the Lunyu or the Shijing?  How important is it to be literal?  Is it better to be literal (explaining the allusions in footnotes), or capture the essence in a less literal way (also with footnotes, this time laying out the literal)?  Is it possible to convey any sense of the visual element of Chinese characters?  How do you explain – not in a footnote, but with your word selection – the various associations a single character can pull up?  One of my favorite characters in the Chinese language is xiao:

è•

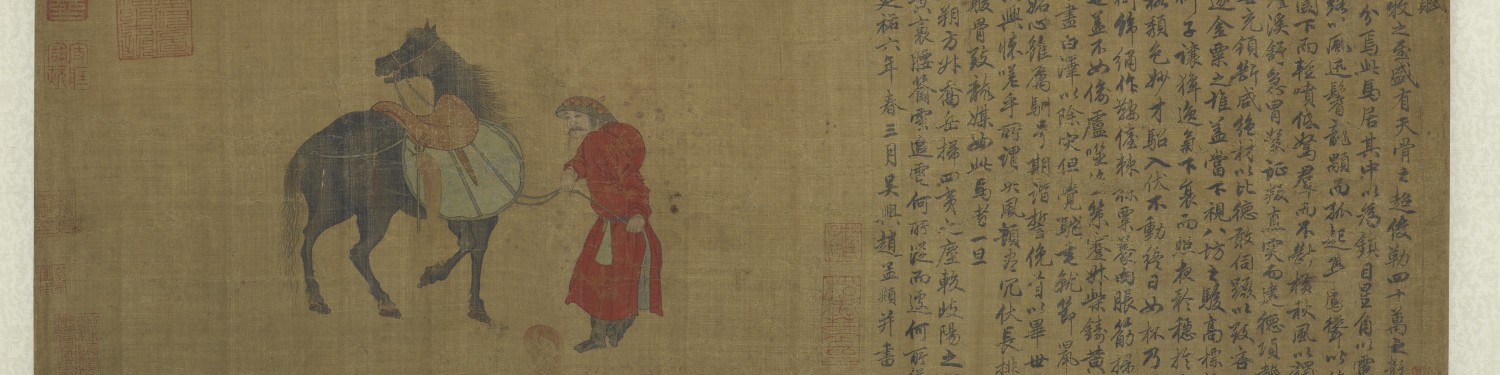

It has a whole host of mournful associations.  Going through a dictionary (this is one I always look up for an initial assessment of the usefulness of a Chinese-English dictionary) is likely to turn up all sorts of compounds, including the rustling of autumn leaves, the sound of wind in the trees, autumn this, sad that, dying, dying, desolate.  Also the whinnying of horses.  Which may sound like an odd fit, but it can be a terribly mournful sound in many respects.  In Li Bai’s famous “Sending off a friend” (one of my favorite Li Bai poems), he closes the poem – sends off his friend – with “è§è§ç马鸣,”  the ponies cry xiao xiao.  How to translate that?  Whinnying doesn’t quite capture it, but xiao xiao means little if you don’t know what character it’s referring to …. I consider myself reasonably talented with English, but perhaps I’m missing some poet’s sensitivity (or perhaps, some of this stuff is just a tad too ephemeral to really nail down perfectly).

This pops up even in modern Romance languages, of course – one of my favorite examples is from the French poet Jacques Prévert and his famous poem “Barbara.”  Prévert is lovely in French, less so in English translation – because his language is so easy and free and, well, French.  It loses some of that in translation.  But the conundrum above (which I’m currently fighting with) was introduced to me clearly here:

Et ne m’en veux pas si je te tutoie

Je dis tu à  tous ceux que j’aime

Même si je ne les ai vus qu’une seule fois

Je dis tu à  tous ceux qui s’aiment

Même si je ne les connais pas

“And don’t mind if I address you using you. Â I say you to everyone that I love, even if I’ve only seen them once.” Â There’s really no way to render it well into English, at least not literally – tutoyer means to “address someone using tu,” or the informal (singular) version of “you.” Â And he plays on the informal aspect – “I say you to all those who love, even if I don’t know them.” Â In English, it just sounds strange. Â But of course, translating it “Don’t mind if I address you familiarly” is not literal, although it conveys the meaning much more clearly than “I call you you.”

So I understand sometimes why people say that things “shouldn’t” be translated, or “can’t” be translated; it’s true that you miss a lot. Â Vergil forever ruined English poetry for me (rather, poetic devices) when I read a particularly spectacular section in the Aeneid. As he talked about the waves in the sea in the middle of this tremendous storm, you could literally (assuming you scanned the line properly and attempted to read it correctly, word stress and meter stress and all) hear the waves, waves that went up … and down … and up … and down. Â Just off the meter and how it interacted with the words. Â It was magnificent – and totally impossible to translate that experience into English. It also made all the “wonderful poetic devices” English teachers in high school loved to fawn over totally yawn worthy in comparison.

But I also think it such a silly view point.  I never would have become a Chinese historian if I hadn’t fallen in love with classic Chinese works – both more modern and much older – in translation.  I fell in love with Roman lyric in translation first.  To say that you shouldn’t get to experience things unless you can appreciate them in their original tongue is shortsighted, to say the least.  I am very glad that I can read and enjoy Latin and modern Chinese and French literature, and sort of enjoy older Chinese literature (for the allusions themselves can – and do – fill books, so there’s always a little doubt in my mind to whether or not I really get the whole thing).  I am also glad I can read Tolstoy, the Man’yÅshÅ«, Sei Shonagon, and Lady Hyegyong – even though I don’t know Russian, Japanese, or Korean, among a great many languages.

In any case, as I trundle through a translation – simultaneously fighting with the language and how to frame it for the specific audience it is geared to – I have an ever-greater appreciation for those intellectual giants who manage to make it look so easy.