Kris Ligman had a nice piece over at Pop Matters on class and games (RPGs, more specifically) – the class-blind, wonderful lands of opportunity that they are:

Is there any ludonarrative dischord greater than the capitalist, white, middle-class attitudes of unrestrained play coming into conflict with issues of class and race so utterly failed by these biases? The class- and race-obliviousness of these pastoral, easy, and free game worlds don’t reflect the lives of the serf characters that we so often assume but reflect their lords instead.

(The essay is worth reading, so go take a look; however, it’s just sort of the tangential jumping off point for what follows)

From Romance of the Fruit Peddler (Laogong zhi aiqing, 1922); baddies of Shanghai's dirty underbelly playing mahjong at an all night club

This got me thinking about the subject of ‘fairness’ in games, at least in the few that I’ve dealt with directly. Â I’ll say off the bat I’m more interested in perceptions of fairness – how people have talked about it – versus technical definitions of whether a game is fair or not. Â Mostly because the world that Ligman talks about, the ‘middle class’ world we inhabit in RPGs regardless of a character’s origin story, is a ‘fair’ world, right? Â Limitless opportunity, bounded only by your own playing. Â The deck isn’t stacked against you from the get go, no matter where you come from! Â It’s a meritocratic fantasy.

The meritocratic bit is what turned me to my own research.  I tackled the subject of mahjong (sort of) for my third year research project.  The paper certainly could have turned out worse, but mahjong was an unexpectedly tough topic to handle in two quarters.  For a game that is so quintessentially Chinese, mahjong is everywhere – and nowhere at once.  Everyone was playing it, and no one was leaving a written record.  Which reminds me: people who whine and moan about the ‘enthusiast press’ and blogs and a lot of ‘noise’ in the game community ought to take pity on future historians, ’cause they (the PhD students of Ivory Towers future) are going to want all that stuff, no matter how poorly written – I promise.

In any case, in half of the paper, I hamfistedly blundered around grappling with old school scholars like Huizinga and Callois (both of whom loved to trot out “ancient China” as an example); in the other half, I attempted to analyze the shifts in discourse surrounding mahjong as related to class and gender.  Mahjong is descended from madiao, a game that Wu Meicun (a famous Ming-Qing scholar-official) claimed “lost the [Ming] dynasty.”  Wu’s meaning was that officials were too engaged in things not related to their job (which would include a ‘frivolous’ game like madiao) and ignoring the barbarian hordes agitating on the northern border (and worse).  It was a game that was beneath the scholar elites to talk about and write about, but it seemed everyone was playing it.  Mahjong retained the decadent overtones of its predecessor (a symptom of moral decay – and harbinger of terrible things, like dynasties being toppled) – and like madiao, everyone played it, and few wrote about it, except in high-handed, pedantic tones.

It wasn’t that games were bad. Â Mahjong and madiao had and have a foil, that being the ancient and eminently respectable game of weiqi. Â Weiqi is also quintessentially Chinese, although it’s known widely in the West by its Japanese name (go). Â Legitimately ancient where mahjong and its forerunners were not, weiqi has an entire genre of poetry dedicated to it, and skill in playing was something “real gentlemen” were expected to cultivate alongside ability in painting, calligraphy, and playing the qin (a type of zither). Â Frankly, I’ve never been terribly interested in weiqi, important a game as it is. Â However, my interest was piqued as I picked up an article on weiqi poetry by Chen Zu-Yan. Â As Chen argues, weiqi poetry relies on three major metaphors: “[it] approximates war, offers paradigms for social order, and teaches lessons about humankind’s moral stake in the cosmic game” (643).

A few samples.  One by Liu Yuxi 劉禹錫, on watching a talented Buddhist monk play:

First, I perceived dotted stars in the dawn sky;

Then, I saw soldiers fighting in late autumn.

Your deployment was as wild geese in flight-nobody understood it,

Until the cub was caught in the tiger’s den, and all were shocked. (646)

Another by Fan Zhongyan 范仲淹:

One [weiqi] stone is precious as a thousand ounces of gold;

One line on the board as crucial as a thousand miles.

Deep thought infuses the spirit;

How can the vicissitudes of the scene ever be replicated?

Success and failure depend on character;

I should compose a [weiqi] history. (647)

and my personal favorite, a painting inscriptions by one Cha Shenxing 查慎行:

The cosmos is a [weiqi]Â board,

The battlefield of Black and White —

Trivial as worms and ants,

Great as marquises and kings. (650)

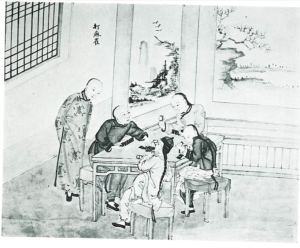

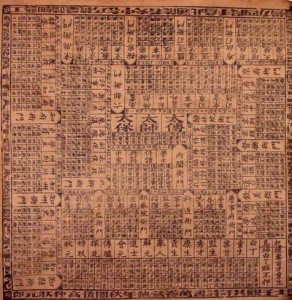

A Qing dynasty (1644-1911) version of the bureaucratic promotion game

All of which is to say, weiqi was serious business (it still is in many respects, with weiqi results appearing on sports pages!). Â I was intrigued by this approach to weiqi, an abstract game that had a wide variety of meanings read into it. Â Mahjong, too, is a reasonably abstract game, and also has a wide variety of meanings attached to it – primarily negative ones. Â In fact, some dour literati lambasted mahjong for the same qualities that weiqi was praised for.

While on a trip to use the UCLA collection, I idly mentioned to my advisor a type of board game (often called shengguantu å‡å®˜åœ–) I hoped to write a paper on someday.  Based around the civil service system and bureaucratic promotion of the Ming and Qing dynasties, these games played like snakes and ladders and were based on a roll and move mechanic (the image at right was taken from the page here, which has more images and descriptions in English).  My advisor asked a bit about how the game was played and remarked that it perhaps indicated that people already felt success in the civil service system was a matter of luck – something like getting a good (or bad) roll in promotion games.

This was an interesting thought, because one of the ideas behind the civil service examination system we are most familiar with in the present day is that anyone – assuming you were male, of course – could succeed in the system.  All you had to do was prepare yourself to sit for the exams, take and pass said exams, and off you could go on your way to fame and glory as an official.  In theory, this wasn’t far off the mark.  In practice, the financial resources (among other things) required to support exam candidates as they crammed for years on end meant that Farmer Zhang’s eldest son chances of success were almost certainly inferior to Magistrate Lu’s kid.  The system wasn’t fair, even though it was an improvement over systems that were more rigid.  There was the potential for social mobility.

I came to feel that this potential is one of the things that biased the literati elites against games like mahjong. Â The yarns spun around weiqi upheld the potential for mobility. Â Weiqi, in theory, was all about self-cultivation. Â The ideal wasn’t a naturally talented player who intuitively grasped strategy and was just plain good at the game. Â The ideal was someone who cultivated the skill of playing, just as one cultivated playing the zither, or painting, or writing poetry. Â Ability in weiqi is nested in beliefs in a meritocratic system where “anyone” could succeed. Â It’s not based on luck. Â The game isn’t biased against you from the start. Â Ability is up to personal virtue in cultivating a skill. Â Despite the fact that it’s a game for two players (and a great number of poems and paintings depict bystanders hanging around a game), it’s often presented as a very solitary activity. Â Consider the following quote from a Song official waxing rhapsodic on the acoustic qualities of his quiet tower:

It is a good place to play the [qin], for the musical melodies are harmonious …; it is a good place to chant poems, for the poetic tones ring pure …; it is a good place to play [weiqi], for the stones sound out click-click. (644)

Weiqi fantasy land!

Games like mahjong and madiao require skill, of course, but have that dastardly element of luck (enemy of meritocracies? Â Perhaps that’s too strong a statement) and multiple players. Â It is possible, though unlikely, to win a mahjong game simply by the luck of the draw. Â I don’t recall reading a specific critique of mahjong or madiao in this vein, but my advisor’s statement about luck and the shengguantu games got me thinking. Â The question of how people talked about the bureaucratic promotion games remains for another day, but I do feel comfortable at least speculating that at least part of elite discomfort with mahjong is the fact that it confronts the lies of the meritocratic fantasy. Â Personal cultivation and hard work isn’t enough, wasn’t enough, and never had been enough: a healthy dose of luck and besting your competition were required to claw your way to the top. Â Sitting alone in your lovely tower listening to the click click of weiqi stones wasn’t going to secure an appointment as an official.

A critical look at weiqi proves that it was hardly the meritocratic fantasy land generations of poets had praised. Â An important skill for aspiring officials to have was the ability to gracefully (and very subtly) throw a weiqi game in a superior’s favor. Â That is, you had to know how to lose. Â No one likes an upstart, even a virtuous and cultivated one (perhaps especially not a virtuous and cultivated one). The practice of purposely losing has roots elsewhere and is certainly quite common, but it raises questions about the element of self-cultivation. Who’s to say that “talented” official wasn’t just being lost to by younger, more talented officials who were hungry for success? This is another thread I never saw directly addressed, except in satirical pieces. Weiqi, at least in the sources I looked at, remained wrapped in a veneer of equality and potential.

The point of all this rambling is that setting aside 20th century Western, middle class, capitalist notions of free play, people in a non-Western, “non-modern,” non-capitalist society liked play to be safely nestled in the same fantasy that contained the more “important” facets of life (like securing a job in the civil service). Â And a number of them really didn’t like it when they were confronted with the evidence that there was a lot to life that was unfair, both on and off the board game table.

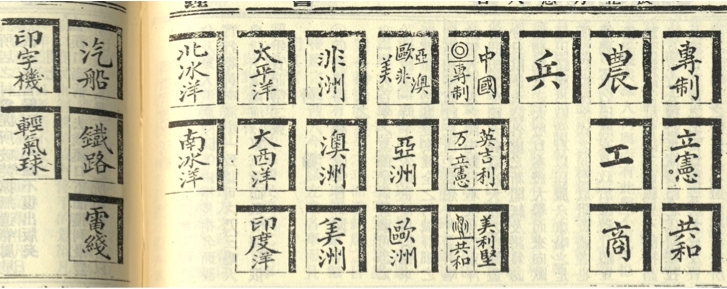

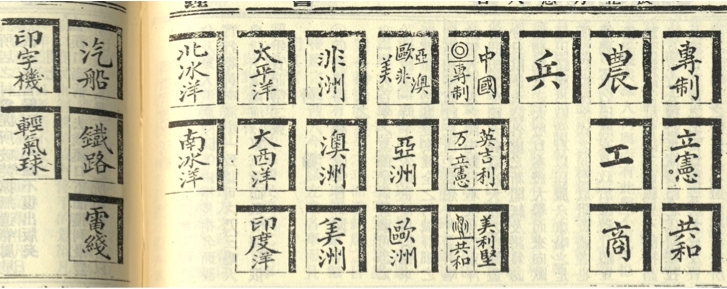

Mahjong goes serious (1904)

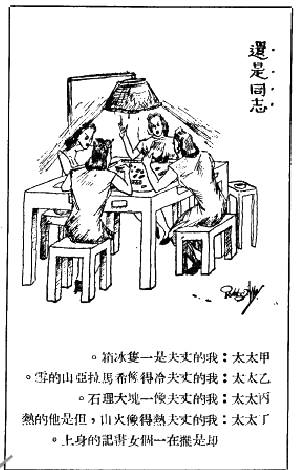

Probably more directly related to Ligman’s original post is the gem above, one of my favorite finds. Â This is a “serious game” from 1904, and deals with capitalism, imperialism, and modernization. Â It was found on the pages of a radical Zhejiangnese newspaper, and was tucked in between news reports on the Russo-Japanese War and other Very Serious Subjects. Â I’ll quote myself from elsewhere here, since I don’t have anything extra to say at 10 PM on a Thursday a year after I last looked at this paper:

The game dreamed up by the author bore little resemblance, either in tiles or in play, to any variation of mahjong, and the “educational†purpose is painfully obvious. The zhong, fa, and bai tiles were replaced with government types (autocracy, constitutional monarchy, and republic), while the directional tiles were mapped to four classes of people (farmer, worker, merchant, and soldier). The three suits were assigned one continent per suit (Asia, Europe, the Americas); each of the nine tiles per suit was assigned a country and corresponding government type (e.g., “China – autocracy,†“England – constitutional monarchy†and “Brazil – republicâ€). A variety of tiles replaced the traditional flower tiles: the five inhabited continents, the five major oceans, and technological innovations (steamship, railroad, telegraph, printing, and hot air balloon).

…[The] essence of the new rules may be summed up thusly: republicanism and technology ruled the day. Players facing a hand of autocratic nations or, worse yet, Australian and African tiles had a near impossible task in front of them, being placed at an automatic disadvantage in terms of “turns†(fan), or ability to draw new tiles. Dominance in this “reformed mahjong†… required the right government and the right technology: the player stuck with the “colonized people†tiles (Africa and Australia) had no hope of competing with the enlightened continent of Europe, and possessing technology alone would not save an autocratic China.

While the rules make some measure of logical sense … even the author recognized the complicated nature of the game, asking readers to offer up suggestions if they thought of any ways to simplify the game. Further, in the pursuit of “educating,†this reformed mahjong seemingly removed any semblance of fun, and it is difficult to imagine anyone willingly settling down for a thrilling game of “imperialism in action.†The obviously educational component seems off putting to the extreme, and there is no evidence that this reformed mahjong made it any further than the pages of the [paper].

The “imperialism in action” statement is perhaps a bit too much of my own opinion creeping in. Â But I think this little ‘reformed’ gem points to the same problem that Ligman’s piece raised for me. Â Namely, the sort of people who would appreciate a game of “imperialism in action” – or being taken out of the meritocratic RPG fantasy and forced to grapple with the injustices of discrimination and inequality – aren’t the sorts that the game(s) are being aimed at. Â The anonymous author of the above mahjong set was aiming the theoretical game at the vast masses of people who he desperately wished were doing something productive with their mahjong time. Â The people most likely to play the game were people like himself: the kind of people who didn’t need Imperialism 101 in mahjong form to take a look at the situation facing them and their country. Â I suspect that for a great number of people, the very fact that the game wasn’t fair would’ve been an extreme turnoff. Â And when I mean “not fair,” I mean that it was possible to find one’s self in a position that took away any hope of winning – by the very virtue of the hand dealt you.

Not so unlike the reality of class, race, gender, and education, eh?

(I’m sure someone’s written about perceived fairness in games; if anyone has any good suggested reading, please send it along.)

—

Chen Zu-Yan, “The Art of Black and White: Wei-ch’i in Chinese Poetry,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 117.4 (Oct-Dec 1997): 643-653