The last time I bothered to sit down and write a post was last summer (over 6 months ago!), when Leigh Alexander wrote a beautiful piece that moved me to write (for once, it landed me on the Critical Distance year-end round up, which tickled me). There have been things since that I would have liked to have written about, perhaps, but professional writing (e.g., manuscript stuff, editing stuff, article stuff – everything else stuff) has stopped that. Actually, the past fall semester has been pretty traumatizing from multiple perspectives, and my ability to get anything done other than what is Absolutely Required has been somewhat compromised. I haven’t been reeling from any particular event – and I have been most thankful for the wonderful people in my life, both here in MT and elsewhere – but just a general sense of being unsettled, and various minor issues, have left me feeling rather defeated on the whole.

But it’s a new year and – more importantly, from my perspective – a new semester is about to kick off. One thing I love about the rhythm of academic life is that things change. Anyone who knows me knows well might find this a weird comment: I generally don’t deal with change and upheaval very well. But there’s something nice that, at least where teaching is concerned, the slate is wiped clean on a regular basis. It does mean I occasionally find myself missing dynamics from classes and students past, but I really love trying new things, making new connections, reading new books – even if it doesn’t always work precisely as I’d want.

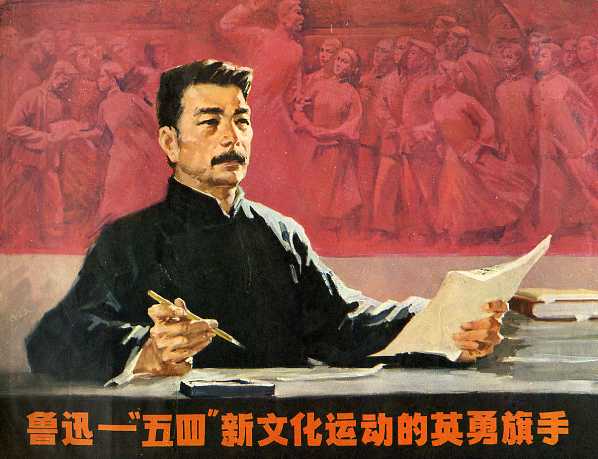

When I started my PhD, I had two thoughts that stuck with me for years: (a) I don’t like teaching much and (b) I will never be good at this. I remember – my first year, before I was an ‘official’ TA (just a ‘reader’) – my very first time being placed in charge of a classroom without a professor’s watchful eye. I paced in front of a room & clutching my battered copy of Diary of a Madman and Other Stories (Lu Xun), which included the assigned readings for the week, practically begging the students to say something – ANYTHING! To this day, I don’t think I do a terribly good job teaching Lu Xun (even though all of my students know I adore him). My advisors commented in a year end review my first or second year that I would “probably turn out to be a very good teacher - if her students can keep up with her” (a nod to my motormouthedness, among other things. I thought of that comment when I caught myself at dinner a few weeks ago – in response to a question of ‘When did foot binding start?’ – animatedly carrying on at mach 10 (‘Oh, well, it goes back to this story, but actually if you look at the archeological record it seems that it started here, perhaps, and they were actually binding the feet to be narrower – not the shape we think of – well, we think, we don’t know, but wouldn’t it be weird to wear socks that didn’t match the contours of your feet?’), before saying with a bit of embarrassment: ‘Well, I could go on for ages, this is something I teach about, so stop me if I’m getting pedantic.’)

I did a lousy job teaching Lu Xun, but at least I looked good at the quarter-end award’s ceremony for the course

The first class I taught on my own (“Women and the Chinese Revolution”), in my fifth year of grad school, was, to put it lightly, not very successful. It was unsuccessful for a variety of reasons, but it was one hell of a learning experience. And then I didn’t teach again for nearly 18 months. While my first semester at MSU was a bit bumpy (to say I was ‘a little nervous’ heading into it would be an incredible understatement), I started to hit my stride – by the spring of my first year, I really started to enjoy it. Academics sometimes treat teaching as that thing we have to do between doing things we want to be doing; but I tend to get a fair amount of energy from teaching (at least when it’s going well), and it helps me structure my days. The least productive periods of my academic life have coincided with having the most “freedom” (i.e., no teaching responsibilities). I spent a lot of time staring at walls and panicking.

In any case, coming off a semester that was a bit of a downer from multiple angles, I’m eager and ready to get back to the classroom. I am teaching one of my perennial favorites – Gender in Asia (pre-modern edition!) – and am so excited to be teaching with some of my very favorite things: the KagerÅ nikki, my beloved, battered Chinese women writer’s anthology (dog eared and marked up, a purchase I made in Taiwan before I even started grad school – for the then-princely sum of 1225NT, around $35), Chunhyang, Sei ShÅnagon, Susan Mann and Dorothy Ko’s scholarship …

In any case, coming off a semester that was a bit of a downer from multiple angles, I’m eager and ready to get back to the classroom. I am teaching one of my perennial favorites – Gender in Asia (pre-modern edition!) – and am so excited to be teaching with some of my very favorite things: the KagerÅ nikki, my beloved, battered Chinese women writer’s anthology (dog eared and marked up, a purchase I made in Taiwan before I even started grad school – for the then-princely sum of 1225NT, around $35), Chunhyang, Sei ShÅnagon, Susan Mann and Dorothy Ko’s scholarship …

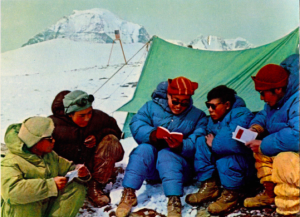

But just as exciting as revisiting old friends (and getting to introduce them to a new crop of students) is a brand new (for me) seminar I’m teaching, History of Mountaineering (Greater Ranges edition). One of my colleagues – who also works on the history of mountaineering – got the seminar on the books a few years ago. As it turns out, Montana is a great place to offer classes on things like “mountaineering” (who would’ve thought?) & it was really popular. I found presenting the bare outlines of my next research project at the mountain studies conference last spring really exciting and stimulating, so when I found out my colleague would be on sabbatical this year, I begged to teach the class. Since he’s an all-around awesome colleague (and human), his answer was ‘Sure, I just put it on the books – it’s not my class.’ Since we come at mountaineering from two different angles (he is most interested in the history of European & American mountaineering; I am most interested in high-altitude mountaineering and mountaineering in the Greater Ranges of Asia), there’s some nice cross-pollination that happens when we talk mountaineering history & the classes are pretty complimentary.

In any case, I am really really really really really excited about this class (really. Really!). We have a whole whack of cool things to read, from classic narratives of first ascents and Western derring-do in exotic locales, to fascinating academic work like Sherry Ortner’s Life and Death on Mt. Everest. And a whole bunch of other things besides – Daphne du Maurier’s haunting novella “Monte Verità ,” news articles, academic articles on … eating and shitting on Mt. Everest? But one of the most novel things about the course is that – for once – I actually have the opportunity to really blend my research and teaching lives.

In any case, I am really really really really really excited about this class (really. Really!). We have a whole whack of cool things to read, from classic narratives of first ascents and Western derring-do in exotic locales, to fascinating academic work like Sherry Ortner’s Life and Death on Mt. Everest. And a whole bunch of other things besides – Daphne du Maurier’s haunting novella “Monte Verità ,” news articles, academic articles on … eating and shitting on Mt. Everest? But one of the most novel things about the course is that – for once – I actually have the opportunity to really blend my research and teaching lives.

Colleagues often say to me ‘Oh, you just need to leverage classes for your research!’ In my case, this really isn’t possible – most of the stuff I do is flat-out inaccessible in English, and while I would like to think I could hang on to students with a course built around Serious Academic Tomes on 20th Century Modern Chinese Cultural Production, I’m not delusional and do try to be somewhat appealing. But the ‘mountain class’ – as I’m already affectionately referring to it as – is a chance for me to read some things I haven’t read, ponder some stuff (very important background stuff for my next research project) from perspectives I haven’t, and get some intellectual stimulation in a seminar setting once a week. I’m thrilled.

Of course, it’s possible things are going to crash & burn (not all classes turn out well!), but I have a good feeling & I’m going with it. I’m looking forward to Wednesday – the first day of spring semester – and a fresh start. I’m looking forward to a favorite person arriving for a visit to Bozeman on Tuesday, and flinging myself at them for a long-overdue hug (and boy, is the dog going to be beside herself). I’m looking forward to my birthday next week. I’m looking forward to my annual celebration, featuring a true Montucky fusion experience: venison and elk bulgogi (last year we just had venison!).

A close friend has said that I’m ‘one of the most sentimental people’ she knows, and I have said – with little shame – that I’d be right at home with Victorian sentimentality. I thought of that the past few weeks when – being sick with a nasty, lingering cold, tired and sore, but unable to sleep – I went back to some of my favorite music from years past, Taiwan’s Betel Nut Brothers (檳榔兄弟 Binlang xiongdi). The group was (is?) a producer of wonderful traditional, folksy-bluesy, music from the Pangcah (Amis) people, one of the indigenous groups in Taiwan. I listened to a couple of their songs, as I have many times over the past six or seven years, while trying to fall asleep – especially my favorite, é’蛙的眼ç›, “Eyes of the frog,” which makes me think of well-loved people who are far away. But when awake, all I wanted to do was share it with new people.

I spend a lot of time looking back; not necessarily being mired in the past, but reminding myself of good stuff that has happened so I can hopefully look forward to good things that will happen (I hope. If I can get out of my own way). I’ve been a little melancholy the past week, so it’s nice to remind myself that I do look forward to and get very excited about change and new things, at least in one part of my life.

Onwards, comrades.

As I’ve noted before, academia can be full of pretty strange transitions – the leap from grad student to professor is an enormous one. A year and a half in, and I can say with some confidence I’m getting settled, but of course – this is not an overnight process. I’m lucky to be at a university where I have a lot of latitude with my teaching, so in addition to drilling down on my core classes (like the general modern East Asian history survey course, which I teach once a year), I’ve been experimenting with classes I may or may not ever teach again. But just because I don’t get a perfectly working syllabus out of a course doesn’t mean it’s a waste of a prep. I taught a slightly harebrained course on memory & culture in 20th century East Asia this past fall, and while I don’t think I’d ever try and do that again (at least, not as I had it set up!), I did get some fantastic feedback from my students regarding readings and films, general structure and themes, etc. that I will be incorporating into future courses. I try hard to be upfront with my students that a lot of things (like their professor) are works in progress & like soliciting feedback on what they liked (or didn’t), and I’ve generally been rewarded with really helpful commentary. So at least at the end of a semester, I can usually say I went out on a limb, it didn’t entirely work, but hey: I learned a lot & next time will be better.

As I’ve noted before, academia can be full of pretty strange transitions – the leap from grad student to professor is an enormous one. A year and a half in, and I can say with some confidence I’m getting settled, but of course – this is not an overnight process. I’m lucky to be at a university where I have a lot of latitude with my teaching, so in addition to drilling down on my core classes (like the general modern East Asian history survey course, which I teach once a year), I’ve been experimenting with classes I may or may not ever teach again. But just because I don’t get a perfectly working syllabus out of a course doesn’t mean it’s a waste of a prep. I taught a slightly harebrained course on memory & culture in 20th century East Asia this past fall, and while I don’t think I’d ever try and do that again (at least, not as I had it set up!), I did get some fantastic feedback from my students regarding readings and films, general structure and themes, etc. that I will be incorporating into future courses. I try hard to be upfront with my students that a lot of things (like their professor) are works in progress & like soliciting feedback on what they liked (or didn’t), and I’ve generally been rewarded with really helpful commentary. So at least at the end of a semester, I can usually say I went out on a limb, it didn’t entirely work, but hey: I learned a lot & next time will be better.