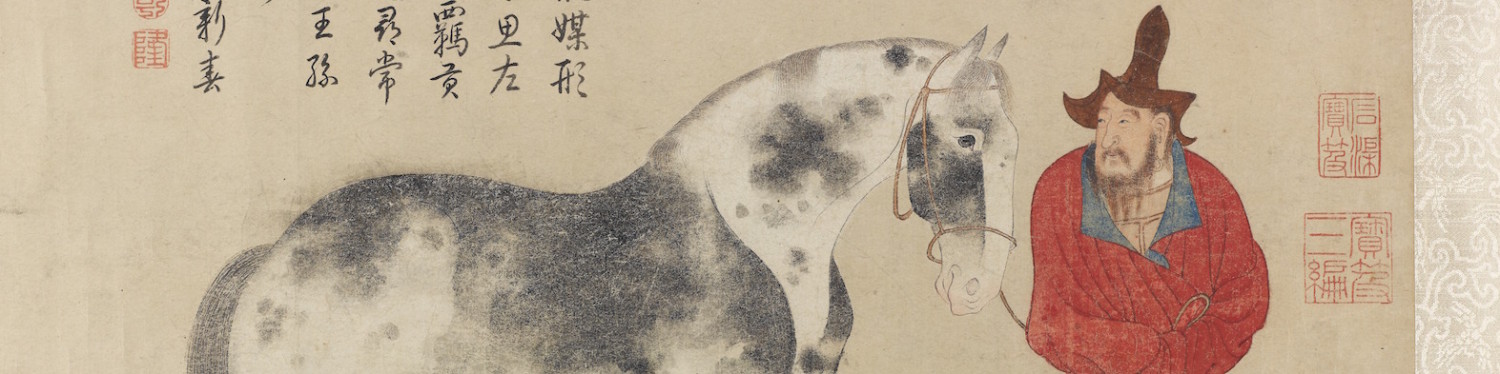

Li Huiniang (who else?)

We read a great essay (which I of course cannot find now) when I was taking my methods class as an undergrad; the gist of it was that doing history can make for the loneliest profession.  We find ourselves growing attached to people who are long dead, and who don’t care about us (they can’t, being dead) – yet we care deeply about them, become familiar with them on intimate levels.  They become part of us in a way that we never become part of them.  Truthfully, I never really felt “lonely” – I’ve always approached history with a bit of Mengzi’s “looking for friends in history” description in mind.  It’s generally a friendly place, and an exciting one, to be in.

I didn’t feel lonely until I started studying someone most people had never heard of and who left a relative dearth of written materials (at least, for a writer!) – yet there I was at home, plowing through sources, trying to get at someone I had very little familiarity with and having precious little to go on, both in terms of his own writing and any secondary sources helpful to the cause. Â What I wouldn’t have given to be able to speak with him, or read his diary – or do anything to get closer to the life of this author. Â But as I read more and wrote more, I got more and more attached to this person – even though I had (at least as an undergraduate) written papers focused on a single person, I had never grown as attached to them as I was (am) to Meng Chao.

So it was with some relief I discovered plenty of people had remembered Meng Chao and had written eloquent memorials to him. Â They’re not all serious; one of my favorites was written by someone who had been in Guilin with Meng Chao in the 1940s, during the war with Japan. Â The author recalled that Meng Chao was perpetually in motion, always running everywhere, and while everyone else struggled with getting essays written, he seemed to have an uncanny ability to put pen to paper and just write. Â It is such a different picture from the defeated septuagenarian – the Meng Chao I first came to know.

The first time I cried out of sadness (not frustration!) while writing a paper was when I had to write the story of Meng Chao during the Cultural Revolution; while I’ve certainly read plenty of history that has made me cry, I had never had to write anything myself that made me unbearably depressed. Â Part of that was having to work off documents that had been written by those close to Meng Chao, and they were so full of affection for the man, and anger and bitterness for what had happened to him (and all of them – all of China, really) – it was difficult not to be moved in some way. Â An essay written by one of Meng Chao’s daughters was full of pent-up vitriol and anger and grief; an essay by his friend and fellow writer, Lou Shiyi, was more tempered, but it still has a biting sarcasm that doesn’t translate well, a sharp and bitter edge. Â Even though plenty of people suffered a lot more for having done a lot less, it was the first time I had to write a narrative that just about broke my heart – working off sources that did break my heart.

Lou Shiyi

Below are parts of Lou Shiyi’s essay, titled simply “I think of Meng Chao” (a partial, mostly uncleaned up version of an earlier partial translation I did), first published in People’s Daily in 1979 (three years after Meng Chao’s death). He has some real zingers that do translate pretty well, but a lot of the language is sarcastic to the extreme (at least, in terms of particular word selection), and it’s difficult to convey how sharp it is in Chinese without copious footnotes. Â While I wish I could get my hands on something – anything – written by Meng Chao having to do with “the Li Huiniang problem,” it is comforting to know that he was loved, people did remember, people did care. Â It is helpful to have their takes on the “problem,” their memories of those 13 years.

It’s of course wonderful to have more sources (as always), but on a less academic, more personal level, it’s nice just being able to get a little closer to one of my subjects and the people who cared deeply for him. Â It helps a little when I get hit with yet another “You study who? Well, I’ve never heard of him” statement. Â It’s nice to know that plenty of people who “matter” more on the spectrum of “important intellectuals of the 20th century” considered him a friend and a talented writer. Â It makes me think sometimes that maybe I’m not barking up the wrong tree here. Â I may not know any of these people (and most of them have “gone to see Marx,” joining the ranks of those who are out of reach on many levels), but I’m not actually alone. Â Making friends in history can be a one sided venture, but it can be comforting, too.

It makes lonely tasks, then, a little less lonely.

from Lou Shiyi, “I think of Meng Chao”

楼适夷 《我怀åŸè¶…》

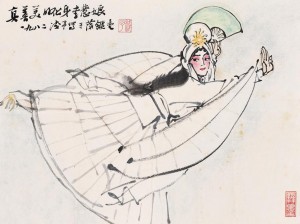

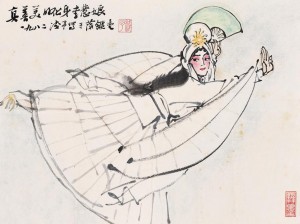

Meng Chao wrote a kunqu script, Li Huiniang; when it premiered, he sent me a ticket. …That day, the theatre was full of familiar friends; the ghost of Li Huiniang entered the stage, her singing powerful and her dance graceful. It certainly appeared like she was enchanting people. Comrade Yan Wenjing happened to be sitting beside me; while he was watching the play, he said gently to me, “Look at Meng Chao, an old tree starting to bloom.†He said this to me, and I knew it was meant with kindness and encouragement towards me, but I was so ashamed I wanted to die.

Meng Chao and I had, in former years, both been members of the Sun Society. He wrote poetry, I wrote utterly muddled short stories. … He published a little volume of collected poems … I love to read poetry, and I remember he sent me a copy, although I’ve forgotten the contents and the title. I really liked it; he proposed to me that I edit a volume, I promised to do so with no hesitation. But it’s easy to promise readily and renege easily … the result was I never edited it. Afterwards, I couldn’t stay in Shanghai and left to sneak a trip to Japan. Two years later, I returned to Shanghai. The League of Leftist Writers had already been formed, but I couldn’t find Meng Chao. Someone else told me, he had “changed his occupation†and was involved in “real work†(at that time, writing wasn’t considered real work), and he was currently squatting in prison. From this point on, I had no news.

Not until the war of resistance was over did I finally know that he had been writing zawen in Guilin, writing plays. After liberation, sure enough, he became a dramatist … we didn’t have much occasion to see each other, but when we had time would we go to the bathhouse to get together and chat. He was the one who told me: there were the fewest people at the bathhouse around noon, and it was possible to avoid lines. And it was also he who told me: this bathhouse in the past was a stronghold of the underground Communist party – if comrades were spotted by secret agents while they were out and about, they’d head for this bathhouse, enter to change clothes, and slip out the back door, shaking off the agents. So we often met here.

The bathhouse attendants all knew him, and knew about the widely reported “trouble†regarding Li Huiniang. They would see me leaving, and they would ask me, “How’s old Meng doing?â€Â Everyone was very worried about him. At the time I didn’t really understand – how could “anti-Jia Sidao†count as “anti-partyâ€? Don’t tell me our great, righteous, glorious, and honorable party was harboring a Jia Sidao? On account of this, this old, flowering tree was nearly cut down for firewood. Meng Chao’s back grew more and more hunched, beautiful Li Huiniang became a “vicious ghost.â€Â Someone wrote an essay called “The some ghosts are harmless theory,â€Â and immediately became an “ox ghost-snake spirit.”  For a short while, a ghostly atmosphere flickered, and we saw ghosts everywhere – everyone was afraid of ghosts, deathly afraid. I was a shallow person, and rejoiced at my good luck, thinking I “had the luck of the lazy,†was an “old tree†who hadn’t “started to bloom,†at last I had escaped by sheer luck. How could I have known that it wouldn’t be long before I was an “ox ghost-snake spirit,†entering a “cow shed†with Meng Chao.

Inside the “cow shed,†Meng Chao was a famous person. Frequently, “young pathbreaking revolutionaries†would burst in and ask: “Which one of you is Meng Chao?â€Â Meng Chao could only stand up and show himself, whereupon they would box his ears, beat him with their fists, and beat his hunched back with a duster. Meng Chao never made a sound, and took the beatings with his head bowed low – seeing this made my heart cold and filled with fear.

Well, we all attended cadre reeducation school. [The cadre in charge of their “cow shed†requested expensive “Red Peony†cigarettes from Meng Chao, which he dutifully provided every day]  On account of this, he was allowed to stay at the reeducation school, and didn’t have to go work in the fields ….

At the reeducation school [some] comrades were allowed to return home to visit family once a year, but we were “ox ghost-snake spirits,†and it wasn’t permitted.  We sometimes stealthily procured a little bit of alcohol to drink. One time, I’d had a few glasses, and counseled Meng Chao: “Didn’t you have that ‘master of theory’ you grew up with? He was really good to you, that day we went to see the premiere of the play, he specially congratulated you and invited you out to eat Peking duck! Why don’t you write him a letter and appeal, maybe you can be released a little early.â€Â Meng Chao didn’t say anything … and shook his head, I also didn’t say anything more.

[Meng Chao broke his leg while getting water from the well] It took a long time to heal.  Finally he was able to drape a tatty padded jacket around his shoulders, rest on a bamboo pole, and silently walk here and there, standing at the edge of the vegetable plot … herding away the old hens of old villagers, so that they wouldn’t ruin the vegetables. After his wife died, to our great surprise one visit home was graciously granted. You could say those “Red Peonies†finally had a good effect.

So the reeducation schools were dismissed. Meng Chao and I returned home. Meng Chao was all alone, and he had to ask an old granny in the hutong to cook for him. I went to go see him when I had time – he was alone, reading Selected Works of Chairman Mao. All of his books had been confiscated, only this one book was left. Sometimes, he’d lean on his walking stick and come to my house to borrow novels. I once asked him: “Meng Chao, any news on your case?â€Â He set his mouth, shook his head, and I didn’t ask again. Some days after he had come to borrow a volume of [Nikolai] Gogol’s writings, I heard suddenly that Meng Chao had died. They didn’t say what big illness he’d had. The hutong granny who cooked him food knocked on his door early in the morning; when he didn’t answer, she had to open the door and go in. She looked, and Meng Chao was lying on his bed, blood trickling from his nose, dead. At that time, the “Gang of Four†was still in power, several friends had to carry his remains on their shoulders to take him to be cremated – in the end, he never got to see the “Gang of Four†fall from power; he just wore his [bad element] cap and  “went to see Marx.â€

Right now, Li Huiniang is back on stages. I just received an official notice that there’s going to be a memorial service for comrade Meng Chao at Babaoshan. I thought – as a reply – I ought to send funerary couplets. I thought for a long time, and finally came up with these two lines:

While living, you were made to be a ghost; for this we should whip the corpse of Jia Sidao three hundred times.

Though you have died, it is as though you still live; for this we should offer solemn song to Li Huiniang.

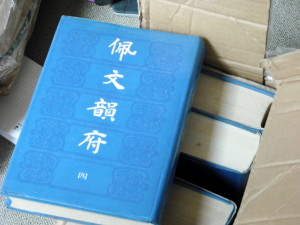

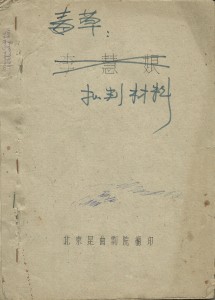

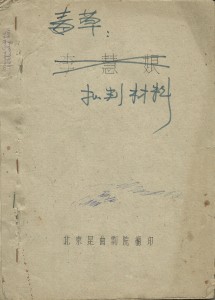

An edition of Li Huiniang used by the Beijing Kunqu Troupe; it is marked "poisonous weed" above the crossed out title - below is noted that it is "evidence for criticism." From my personal collection.

A few notes: Jia Sidao, the villain of Li Huiniang, is often portrayed as one of the great evil figures of Chinese history, hence Lou’s confusion over how an “anti-Jia Sidao” play became “anti-party.”

The “Some ghosts are harmless theory” (yougui wuhai lun æœ‰é¬¼æ— å®³è®º) was written by Liao Mosha 廖沫沙 (under the pseudonym Fan Xing ç¹æ˜Ÿ) in 1961.  He repudiated it in February 1965, in an article that appeared in People’s Daily.

An “ox ghost-snake spirit” (niugui sheshen 牛鬼蛇神) is the term for a bad element par excellence, the worst of the worst of class enemies and enemies of the party.  On being beaten with a feather duster, I initially scratched my head over this – a feather duster?  Fearsome?  However, after seeing some more “traditional” dusters (which tend to be longer and have a wooden rod as a core), I can imagine it would make a perfectly nasty weapon when wielded by zealous teenagers.

The ‘master of theory’ is Kang Sheng 康生.  When Lou Shiyi suggested to Meng Chao that he get in touch with him, he didn’t know that in the days of early criticism of the opera, Meng Chao had presented two letters from Kang Sheng praising Li Huiniang, as well as several photographs and the like (these all disappeared).  At the time Meng Chao did this, he didn’t realize who, exactly, was in charge of his case – as it turned out, it was his old friend Kang Sheng himself.

On a more ancient note, Mengzi’s thoughts on “looking for friends in history” is one of my perpetual favorite snippets of antiquity:

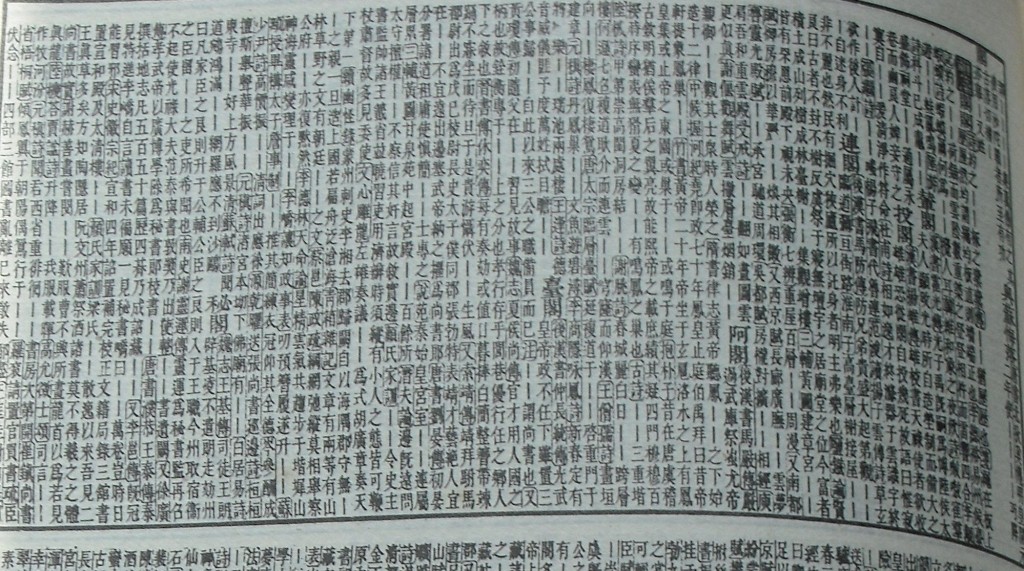

一鄉之善士,斯å‹ä¸€é„‰ä¹‹å–„士;一國之善士,斯å‹ä¸€åœ‹ä¹‹å–„士;天下之善士,斯å‹å¤©ä¸‹ä¹‹å–„士。以å‹å¤©ä¸‹ä¹‹å–„士為未足,åˆå°šè«–å¤ä¹‹äººã€‚é Œå…¶è©©ï¼Œè®€å…¶æ›¸ï¼Œä¸çŸ¥å…¶äººï¼Œå¯ä¹Žï¼Ÿæ˜¯ä»¥è«–其世也。是尚å‹ä¹Ÿã€‚

The best gentleman of a village is in a position to make friends with the best gentleman in other villages; the best gentleman in a state, with the best gentleman in other states; and the best gentleman in the empire,with the best gentleman in the empire. And not content with making friends with the best gentleman in the empire, he goes back in time and communes with the ancients. When one reads the poems and writings of the ancients, can it be right not to know something about them as men? Hence on tries to understand the age in which they lived. This can be described as “looking for friends in history.†(Mencius: 5B8, trans. D.C. Lau)

Research is a funny thing; you sometimes find connections where you least expect them. I’ve been trawling through the database Duxiu, checking up on a few things that have popped up in archival sources. I checked up on a common search (the dramatist Meng Chao – who really made his name as a poet in the Republican period) and turned up an article I’d never seen before. It was published in a journal I don’t usually associate with dramatists (Xin tiyu – on sports and athletics) on a pet subject of mine: high altitude mountaineering. Specifically, the 1960 ascent of Mt. Everest (or Qomolangma), which may or may not have been successful. I’ve been dying to write a paper on mountaineering in China after 1949 – I read one of the few (maybe the only?) academic books on Himalayan climbing last year & it simply increased my feeling that there’s a cool story to be told about China’s role in all of this.

Research is a funny thing; you sometimes find connections where you least expect them. I’ve been trawling through the database Duxiu, checking up on a few things that have popped up in archival sources. I checked up on a common search (the dramatist Meng Chao – who really made his name as a poet in the Republican period) and turned up an article I’d never seen before. It was published in a journal I don’t usually associate with dramatists (Xin tiyu – on sports and athletics) on a pet subject of mine: high altitude mountaineering. Specifically, the 1960 ascent of Mt. Everest (or Qomolangma), which may or may not have been successful. I’ve been dying to write a paper on mountaineering in China after 1949 – I read one of the few (maybe the only?) academic books on Himalayan climbing last year & it simply increased my feeling that there’s a cool story to be told about China’s role in all of this.