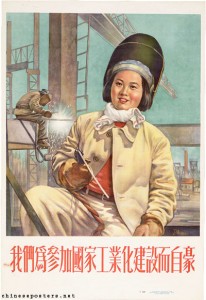

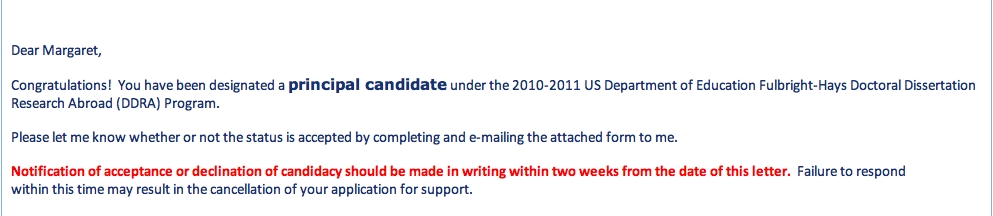

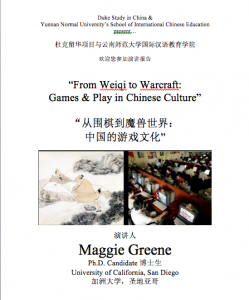

My very first poster advertising ME!

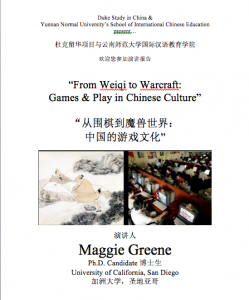

As if I didn’t have enough to do in my last two weeks in China, I enthusiastically accepted an invitation extended by a good friend of mine: come to Kunming (the ‘Spring City’ in China’s Yunnan province) and give a lecture on a topic of my choosing to his study abroad students in the Duke in Chinaprogram.

So thanks to Brent Haas, one of my favorite people from grad school & one of the very finest teachers I’ve ever seen, for showing me a good time in a lovely city & allowing me the opportunity to talk about some of my favorite stuff. As it turned out, the school administration was pretty excited to have a guest speaker, so my audience was significantly bigger (and more diverse) than I was anticipating: around 100 students, most Chinese. What follows is a condensed version of my talk (I also have a bit of discussion afterwords and some thoughts on what I could have done better – things to file away for next time. Here’s hoping next time goes just as well!). The talk itself was a bit basic, but I think I’ve started pulling out some core themes (and in the process of getting ready, came across some more good sources: YES!)

From weiqi to Warcraft: Games & Play in Chinese Culture (and some serious stuff, too)

I have, for about as long as I’ve been in grad school, felt like someone trapped on the margins of two fields. I longingly press my nose up to the window pane of game studies, and wish that I were truly as comfortable being an academic there as I am being, uh, whatever it is my status is (former blogger of some renown at one point in the quickly receding past, at least among certain quarters?). At the same time, I’ve tried to mash myself into what I think Chinese historians ‘ought’ to be (with some success), while at the same time trying not to be that. Mostly, I would just like to feel like I’m doing a better job of straddling two fields that don’t see a lot of each other: I am usually the only historian at game studies things and almost always the only Chinese historian; while I am delighted there are more and more ‘China studies’ people looking at contemporary gaming culture, I don’t think we’ve hit a critical mass – yet. At least, those of us skewing more towards the historical haven’t.

In any case, part of trying to straddle these two worlds is trying to capitalize on what I do have that most people don’t. I tend to fall back to what I know best: the popular press. And here is the real heart of my personal project: I want to flesh out these flat, one-dimensional representations of what Chinese gaming culture (and by default, China) is, and think in broader terms about how we got to where we are today and where we might be going. I went through and culled a small-but-pretty-representative handful of articles on China from Kotaku to illustrate exactly what we are up against:

- Prisoners in labor camps forced to farm gold. Here we have a trifecta of ‘China issues’: gold farming, World of Warcraft, and human rights violations

- Game addicted, neglectful parents sell their children for more money, more time to game

- World Bank proposes gold farming as potential revenue stream for developing economies (this one was more a matter of tone (negative) and photograph illustrating article (Chinese gamers))

- A bounty of counterfeit, shanzhai 山寨 Nintendo DSes seized at Japanese port (this one elicited quite the laugh from my Chinese audience)

- And finally, perhaps the most typical: man in Beijing dies after marathon gaming binge at internet café (wangba)

I certainly don’t want to deny bad stuff happens; on the other hand, it’s an awfully skewed portrait. Well, who cares what a bunch of Kotaku readers think, right? Unfortunately, such a blasé attitude is naïve at best and dangerous at worst; I think the overwhelmingly negative or derisive tone is one that is echoed in many places. There’s also this weird tendency to put China in this Confucian post-socialist vacuum, by which I mean many people see China as consisting of Confucius … then Mao and after … and precious little in between. How often have things been written off as some weird communist quirk? Or how often do people intone about ‘tradition’ this and ‘traditional’ that?

This spills over a touch into academia (the sort of ‘amnesia,’ not thinking China is an odd blend of Confucian traditionalism and communist … something), where the past 10 years sometimes seem to be devoid of a longer history. Often, the most you get is a quick gloss of post-Cultural Revolution, reform & opening (gaige kaifang 改é©å¼€æ”¾). I recognize that not everyone is a historian, nor is interested in being one; but I really hate that a really rich history is essentially ignored. Surely there’s a way to marry these two fields together. So I guess that’s what I’d like to do, recognizing that I’m never going to be a superstar in either field independently. I’ll settle for being pretty decent at mixing them together.

In any case, my goal for the talk was to illustrate (a) the utility of games in studying Chinese history (b) the utility of considering a broader sweep of history when discussing contemporary games and gaming culture and (c) discuss some of the challenges and pitfalls of games research (particularly from the historian’s point of view). I guess it was a bit simplistic, but then, it was a talk to a pretty mixed audience, so I guess that’s to be expected!

I. Liubo å…åš ‘six sticks’

Tomb figures, Eastern Han (25-220 CE)

On the surface, liubo seems a slightly odd choice to begin a lecture on the history of games with, since precious little is actually known about the game. We have some textual references (dating to the Warring States period, 5th-3rd c. BCE) in sources such as the Analects è®ºè¯ and the Mencius åŸå, and physical objects: sculptures, paintings, game boards, paraphernalia. A lovely complete game set was pulled out of the Mawangdui çŽ‹å †é©¬ tombs (circa 2nd c. BCE, Changsha, Hunan), which also included some extraneous pieces that seem to be unrelated to liubo.

But I picked liubo for a few reasons: first, it illustrates the difficulty of studying old games that have died out. Liubo was clearly very important for a relatively long period of time (several hundred years at least), though it began declining in popularity by the later Han and has not been played for at least 1500 years. While extrapolating back from modern rules has its own problems, it at least gives us something to go on. Scholars debate exactly what kind of game liubo was: a racing game, where one had to go from point to point? A battle game, where one had to defend one’s territory? It’s simply not clear, and the texts and objects are pretty silent.

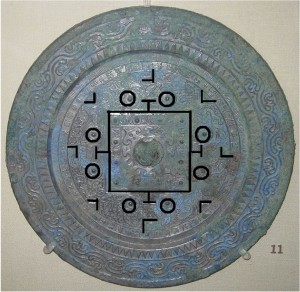

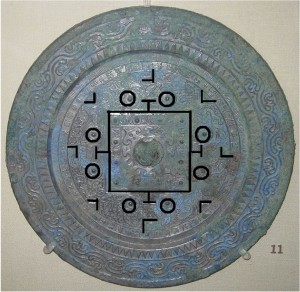

Second, while we really oughtn’t need be reminded that games can be serious business, sometimes people do need a little reminder. Liubo is good for this, as it seems to have had some ritual function. These ‘TLV’ mirrors are so named because of the T, L, and V shapes that appear on their surface. Those shapes just so happen to resemble a … liubo board? Indeed. And one example is even inscribed with wording that informs us the liubo board was inscribed to dispel evil. Well. Again, the link between the game, the mirror, and any ritual functions is pretty unclear. The inscription, while tantalizing, is merely one sentence, and we have no other idea of how these three things – mirror, game, ritual – fit together.

Bronze TLV mirror, 1st c BCE (British Museum), black marks illustrate the liubo board (?)

Finally, liubo overlapped with weiqi and this has caused a massive amount of confusion. I’ll come back to this, as I think it’s very important in understanding part of weiqi‘s history, and by extension, a part of the history of games in China as a whole.

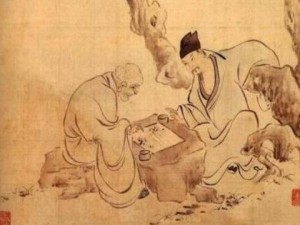

II. Weiqi 围棋 �’encirclement game’

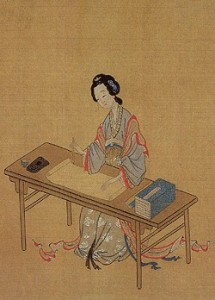

Woman playing weiqi (c. 722) - Painting on silk, Astana graves, Xinjiang

While at the Digital Games Research Association (DiGRA) conference in September 2011, I was intrigued by the number of people who brought up weiqi (or go ç¢, as it is more commonly known). Poor China – one of the most quintessentially Chinese of games is, for most people, forever identified with Japan! In any case, weiqi has an illustrious past, and is still a very popular game that is taken quite seriously. In terms of its history, by the Tang dynasty (618 – 907) it was one of the four arts (siyi 四艺) that a gentleman was expected to have mastery of, alongside playing the qin(zither), painting, and calligraphy. The game was overwhelmingly associated with the male literati-scholar elite, though (as a famous Tang dynasty painting proves) some women played, as well.A piece by Wang Yucheng 王禹å (954-1001), a Song dynasty poet and official, gives us some indication of weiqi‘s importance. After being demoted from his position in the civil service, he built himself a bamboo tower and waxed rhapsodic on it’s soothing qualities:

I … built a bamboo tower with two rooms. It is a good place to play the qin, for the musical melodies are harmonious and smooth; it is a good place to chant poems, for the poetic tones ring pure and far; it is a good place to play weiqi, for the stones sound out click-click.

I personally love the genre of weiqi poetry (see article by Chen Zu-Yan – which the following examples are taken from) – and there are some truly splendid and varied examples.

In Liu Yuxi’s 劉禹錫 (772-842) �“Song of watching a weiqi game, as a send-off for Master Xuan’s journey westâ€� 观棋æŒé€å„‡å¸ˆè¥¿æ¸¸ (written after watching a talented Buddhist monk play), we get an inkling that weiqi is perhaps not as solitary as the game is sometimes presented. Master Xuan was playing another person, and probably had a number of (male) friends standing around watching:

First, I perceived dotted stars in the dawn sky;

Then, I saw soldiers fighting in late autumn.

Your deployment was as wild geese in flight – nobody understood it,

Until the cub was caught in the tiger’s den, and all were shocked.

Weiqi was the best kind of social activity: moral and wholesome while providing a platform for male bonding. Liu’s poem also gives a taste of the martial imagery used to discuss weiqi – proponents of weiqi noted its utility as a military training tool. Weiqi was applied to any number of grander situations, my personal favorite being Zha Shenxing’s 查慎行 (1651-1728)� “Inscription on Zhang Qiji’s ‘Painting of Men Watching a Weiqi Game’â€�é¢˜ç« å²‚ç»©è§‚æ£‹å›¾ (I haven’t yet seen the painting this is based on):

The cosmos is a weiqi board,

The battlefield of Black and White –

Trivial as worms and ants,

Great as marquises and kings.

These examples illustrate a few key points of scholars’ attitudes towards weiqi: its reflection of cosmic elements, its utility as a training game for military strategy, and the connection to self-cultivation that was an important component of Confucian traditions. The utility of weiqi as a military training tool is debatable, considering the lousy track record of Song and Ming dynasty weiqi-playing officials on the battlefield!

But the point of the four arts was not that one was supposed to be innately skilled at weiqi, or painting, or writing poetry: one was to acquire these skills through study and practice. In theory, any ‘gentleman’ could acquire mastery of weiqi: this sort of cultivation was key to the examination system that supported the Chinese civil service. The dream of a meritocracy was increasingly important in the Ming and Qing dynasties, when even Farmer Zhang’s kid could study hard and reach the position of a high official. Or, that was the theory at least. If the cosmos is a weiqi board, the cosmos is essentially fair – because anyone could acquire skill in weiqi (and by extension, life), you just had to work at it. Even Confucius approved of weiqi!

Well … so they say. Here, I crib off of people who know much better than I the intricacies of very ancient texts (the Lien article cited below is really wonderful for an introduction to some of these philological and historical issues). But what can we state with reasonable certainty? We know that weiqi existed by the Han dynasty (the physical record picks up here). Prior to the Han, we see no references to the game – instead, we see references to things like boyi åšå¼ˆ. In citing Confucian classics, historians have relied on what appears to be the anachronistic readings of Warring States texts by Han dynasty scholars. That is, we’ve generally assumed that the boyi of the Warring States had the same meaning as boyi in the Han (since that’s what those Han scholars thought – and that is how they glossed much older texts). I think the most convincing arguments point to this anachronistic reading and make a good case for weiqi‘s later appearance.

Well … so they say. Here, I crib off of people who know much better than I the intricacies of very ancient texts (the Lien article cited below is really wonderful for an introduction to some of these philological and historical issues). But what can we state with reasonable certainty? We know that weiqi existed by the Han dynasty (the physical record picks up here). Prior to the Han, we see no references to the game – instead, we see references to things like boyi åšå¼ˆ. In citing Confucian classics, historians have relied on what appears to be the anachronistic readings of Warring States texts by Han dynasty scholars. That is, we’ve generally assumed that the boyi of the Warring States had the same meaning as boyi in the Han (since that’s what those Han scholars thought – and that is how they glossed much older texts). I think the most convincing arguments point to this anachronistic reading and make a good case for weiqi‘s later appearance.

Here’s where we, as China scholars, have amnesia: it wasn’t until relatively recently that scholars started interrogating these questions seriously. After all, what difference does it make? The game was popular – and has stayed popular. What difference does a few hundred years make? Well, when we’ve erased an entire portion of weiqi’s history, we’re missing a big part of how weiqi fits in with broader trends in Chinese culture and society.

My favorite find of the past several months, YE Lien’s spectacular article on Wei Yao’s 韦曜 (c. 204-273) “�Disquisition on boyi [weiqi]” åšå¼ˆè®º contains the following gem from Wei Yao (keep in mind, this is about that most unassailable, Confucian, glorious, edifying game – weiqi!):

Among people of this generation, many do not engage in classical studies. They like to play board games: they abandon their work and neglect their tasks, forgetting to eat or sleep, using up the whole day and exhausting the sunlight, then carrying on with tallow candles. … Regular affairs are neglected and not taken care of .… Sometimes they gamble for clothing and belongings …. The sense of honor and shame is relaxed, and expressions of anger and perversity are unleashed.

Statements like this are timeless – think of Cicero’s “O tempora o mores” (Oh the times, oh the customs!) – and certainly not confined to China, but think for a moment. This most Confucian of games, a game we talk about as being practically limitless in its multitude of moral qualities, had a period of several hundred years where not only was it not the be-all, end-all of literati board games, it was actively castigated by some quarters as being addictive, dangerous, and bad for the spiritual and physical health of China’s youth.

This tension is (I think) incredibly important to understanding the status of games in Chinese culture, from the ancient times until present, as the tension carries down through the late imperial period to the present day. Yet we’ve spent very little time talking about this tension (or games in general). But had Wei Yao been born in the waning years of the Qing dynasty, his essay would have been perfectly at home. He would have had the perfect target – majiang 麻将 (mahjong).

III. Majiang 麻将 mahjong

Here’s another quintessentially Chinese game – one that was often put in direct opposition with weiqi (unfortunately for China, mahjong has retained its associations with the Middle Kingdom, despite being filtered through Japan – unlike weiqi!). Mahjong was the wild, wasteful, decadent, horrifying other to weiqi’s tempered, wholesome, and educational self. It is a social game for four people, played with colorful tiles; the object is to build certain combinations of tiles – not unlike many card games.

I began researching mahjong at the behest of a professor who indicated he would like to understand the origins of the game which “despite a lot of garbage about Confucius and ancient origins, rose in the Taiping era and apparently from Shanghai, to become an extraordinarily popular form of polite gambling in the twentieth century.â€

Where the game came from and when is impossible to pin down, though it generally appears to have shown up in Shanghai or Ningbo in the middle of the nineteenth century. What is for certain is that the game spread quickly, and was popular from the social and political elites down to peasants.

And while tracing mahjong’s origins is very difficult, there does seem to be a strong link with madiao é©¬åŠ – a game that had been the bane of late Ming officials. Of course, reconstructing games in absence of physical and textual evidence can be next to impossible. Compounding the problem – at least in the case of madiao or mahjong – was the fact that while everyone seemed to have been playing the game, none of the literati elite would deign to write about it. Except, of course, the ones who were criticizing it – and they weren’t kind enough to leave us detailed geneologies of the games they just wished would disappear.

The famous poet-official Wu Meicun å´æ¢…æ‘ called madiao the “game that lost the Ming.†His meaning was that while Manchus massed armies on the northern border, southern officials were busy frittering away their days with games and pleasurable diversions. Madiao, for Wu, was a neat, two character encapsulation of the vices of an official class who didn’t take their Confucian duties too seriously. Thinking back to Wei Yao’s complaints about weiqi over a thousand years earlier, Wu’s criticisms look awfully familiar.

Mahjong’s reputation certainly wasn’t an improvement over madiao’s. But, just like madiao – which it seemed just about everyone was playing, though no one was writing about it – the game was extraordinarily popular. The question of why the social elite loved mahjong is difficult to answer, since no one who liked the game really wrote about why they liked the game. But the mahjong itself may offer some clues.

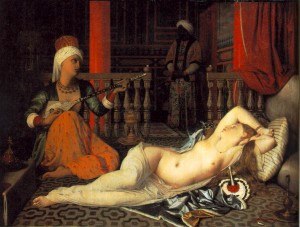

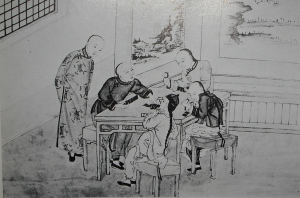

In an early 20th century Japanese text on 'customs of old Beijing,' this depiction of mahjong was flanked by illustrations of an opium den and a "tea house"-cum-brothel

Unlike

weiqi, which is frequently presented as a more contemplative, serious game – almost solitaire in two player board game form – mahjong is a game for four players, less technical, and less contemplative. The social aspects of the game appear to be one of the biggest draws, and one of the reasons late Qing moralists went crazy criticizing the game. It was addictive, people spent too much time on it, and neglected the things they ought to have been worrying about – like a crumbling dynasty (is this sounding familiar yet?). Even people who were worrying about the state of the Qing dynasty and later, the early Republic, loved mahjong: the great scholar and reformer Liang Qichao æ¢å¯è¶… is attributed with the saying that “Only studying is able to make one forget mahjong, and only mahjong is able to make one forget studying.â€

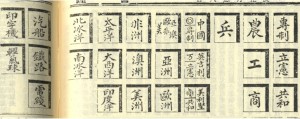

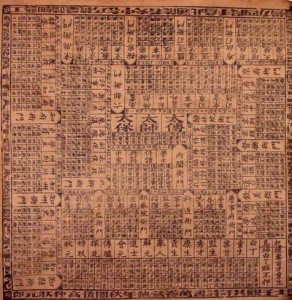

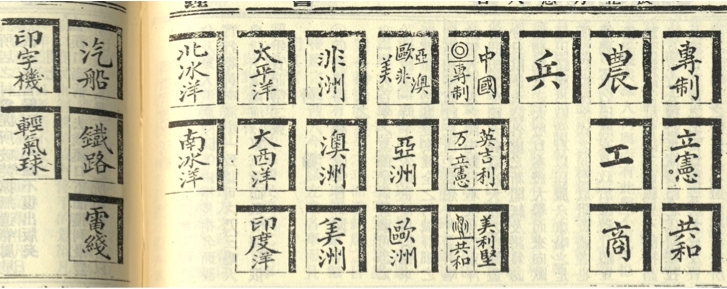

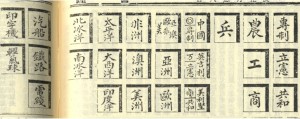

Yet, in a move that presaged efforts a century later, an anonymous author in the radical late Qing Zhejiangnese newspaper “The Alarm Bell Daily†expressed the idea that mahjong was good for more than mindless evenings with friends. Tucked amongst dispatches on the Russo-Japanese War, dispatches from foreign countries, and national news of some importance was an article that suggested games – in particular, mahjong – were perhaps one part of the solution to the myriad of problems facing China.

The game had long, involved, and pretty pedantic rules (see the bottom of this post for a description). The important thing here is that the author felt that mahjong – a wildly popular game – could be used to educate the mahjong-playing masses to the new global order. The point of the game was to illustrate the superiority of Western styles of government, the necessity of technology, and the need for a combination of things (government, technology, resources) in becoming a world power. As far as I know the game never made it to a production run, but the intent was there: using a very popular game, one that was seen as having no purpose or negative influences, changing it a bit, and giving it a new, appropriately healthy and educational twist.

Reformed mahjong

IV. The Present

Reformed mahjong was one glimmer of hope in a landscape that was otherwise stuffed full of criticism and anxiety over where the future was headed. Anxiety over games is (obviously) nothing new, nor is it confined to China. This point is obvious, but too often contemporary issues get spun in a ‘Oh, look what those crazy Commies are doing now!’ manner – that is, some sort of authoritarian overreaction. I don’t want to remove the CCP leadership (on national, provincial, and local levels) from their role in all of this, but there is a lot more to this anxiety and desire to control than ‘the CCP behaving as usual.’ Exactly how all of it ties in, I’m not sure – but it is deserving of more than a passing glance.

Wei Yao’s criticism of weiqi would, as I mentioned before, be very at home in 2011 with a few minor changes:

They like to play computer games: they abandon their work and neglect their tasks, forgetting to eat or sleep, using up the whole day and exhausting the sunlight, then carrying on at all-night wangba. … Regular affairs are neglected and not taken care of .… The sense of honor and shame is relaxed, and expressions of anger and perversity are unleashed.

As I’ve said before, the ‘back in MY day’ sentiment – a nostalgic longing for some better past – is nothing new, nor is it constrained to China. It’s not a unique feature by any means – but it’s one that gets forgotten (we can’t really accuse Wei Yao of being a silly Chinese communist, right?). I think we’ve also forgotten to some degree the cycles that games go through: weiqi‘s past position of being eyed with deep suspicion by Confucian moralists has been thoroughly obfuscated.

Too, the strange Chinese hybrids – the ‘addictive (but not TOO addictive) and fun!’ yet ‘morally wholesome and educational!’ – aren’t a new idea (anywhere in the world!). Government bureaus in contemporary China are finally acting on the same impulse as the anonymous Zhejiangnese author of “Reformed Mahjong”: ““In observing the rise and fall of nations,†he wrote, “one should not observe matters of great importance, but instead look at trifling things.†Mahjong – as a ‘trifling thing’ popular across the whole of China – was the perfect vehicle for reform and education. These days, it’s not mahjong, but MMOs.

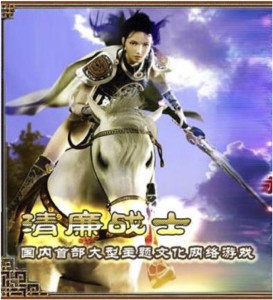

Here’s one of my favorite examples: Incorruptible Fighter (Qinglian zhanshi 清廉战士), a game put together by the Ningbo government. Designed to teach players about corruption and get some history lessons along the way, it was basically a very slightly modified version of the ever popular Three Kingdoms-themed PC game. Incorruptible Warrior appropriated an existing structure and gave it a facelift without making substantive changes to the gameplay itself. Killing the powerful and notorious Ming eunuch Wei Zhongxian, for example, netted players one hundred experience points, with which they could upgrade their stats in “combating corruption,†“moral character,†and “degree of being corruption-free†(these stood in for more usual designations of “strength†or “magic abilityâ€).

Here’s one of my favorite examples: Incorruptible Fighter (Qinglian zhanshi 清廉战士), a game put together by the Ningbo government. Designed to teach players about corruption and get some history lessons along the way, it was basically a very slightly modified version of the ever popular Three Kingdoms-themed PC game. Incorruptible Warrior appropriated an existing structure and gave it a facelift without making substantive changes to the gameplay itself. Killing the powerful and notorious Ming eunuch Wei Zhongxian, for example, netted players one hundred experience points, with which they could upgrade their stats in “combating corruption,†“moral character,†and “degree of being corruption-free†(these stood in for more usual designations of “strength†or “magic abilityâ€).

It’s easy to laugh, but is it actually that different from weiqi? It’ll take another couple of hundred years to find out, but this tension between criticism and adopting something, bad, addictive fun and good, educational fun – it’s been here for a very long time, and by ignoring the connections between contemporary and historical games, we’re really missing a lot.

—-

A bit earnest and very simplistic, I guess, but all in all, not a bad first effort (well, I don’t think so, at least). As it turned out, my audience of about 100 students turned out to be mostly Chinese – I had anticipated a much smaller group composed primarily of Duke University students and perhaps some expats. Had I known ahead of time, I would have put my slides in Chinese – I like to think I’m reasonably good with PowerPoint & there were certainly plenty of images (and not too much English text), but some Chinese language guideposts would have been good. Thanks to the efforts of Professor Haas, we did manage to have some conversation at the end of the talk. A few brave students were willing to talk about their affection for historically themed games (one noted he felt like he was learning something about the Three Kingdom period when he played them), casual games (at least in the case of the girls in the room), and Angry Birds (which everyone, more or less, admitted to playing, after a round of denials that anyone played any digital games whatsoever. Naturally!).

As usual, I wound up giving myself more food for thought and feeling woefully unprepared to ever talk about any of this in a really formal, professional setting. Maybe someday. In the meantime, if anyone stumbles across any mahjong references, send them my way ….

—

Chen Zu-Yan, “The Art of Black and White: Wei-ch’i in Chinese Poetry,†Journal of the American Oriental Society 117.4 (Oct-Dec 1997): 643-653

Y. Edmund Lien, “Wei Yao’s Disquisition on boyi,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 126.4 (Oct-Dec 2006): 567-578