So I’ve had the occasion – thanks to a visit from family – to completely set aside work for about two and a half weeks & just relax.  One thing I’ve found since starting grad school, lo those many years ago, is that “relaxation” is sort of a misnomer for what’s going on when you’re not working.  I tend to be tightly wound and neurotic (several doctors at the clinic on campus have noted with some wonder how tight my shoulder muscles are!), and saddled with a Type A personality with a streak of laziness (a Type A-, perhaps?) – which compounds the neuroses.  In a conversation with an undergraduate contemplating grad school, I opined that separation and compartmentalization can be hard to achieve; work comes home with you, never stays where it’s supposed to, and you can never quite turn off the nagging voice in the back of your head telling you to start working and stop watching TLC’s Toddlers & Tiaras marathon.

In any case, I always have a very long to-do list & this has only gotten worse since I’ve been set loose with only a vaguely defined agenda: “research dissertation” is quite different than, say, “write historiography paper that’s due in two weeks” or “research X topic for the next 10 weeks while updating seminar on progress weekly.” Â I will be trekking up to Beijing at the beginning of April for a two week business-pleasure trip: the pleasure part is seeing good friends I haven’t seen in months and months (or longer), the business part being seeing one of my advisors. Â I am actually quite relieved at the prospect of being able to have a talk – and having a very real, very definite deadline coming up soon has definitely helped my thinking on what work I have gotten done and where I hope to go.

But I haven’t been thinking about that for the past two weeks, no. Â I’ve been mellowing out in a happy cocoon of family and pleasure reading. Â One thing I have been taking a lot more time for since crossing the qualifying hump is reading for me, not for my research. Â My first three years of grad school were stuffed full of a lot of books (of course), but precious few were for my own pleasure. Â Those that were could generally be tied in some way, shape, or form back to research or teaching (I had a six month spate of using late Meiji and Taisho era Japanese fiction as my “bath time fluff” – one never knows when one might be called upon to teach a course and need those kinds of materials! Â I like to be prepared for most reasonable eventualities). Â For once, I haven’t had the overwhelming guilt of “But I should be doing something else!!!”; I’m hoping that this lengthy pause to regroup and rest up will mean better, Â more productive weeks ahead – I really needed a break, and I’m finally getting to the point of being able to take one with only a little guilt.

Last summer, I bought a Kindle on a half asleep, 7 AM whim. It actually turned out to be an excellent purchase – I don’t have to worry about access to English language books in China & I don’t have to worry about storage anywhere. Â It’s actually made me more inclined towards pleasure reading, since I don’t have to go through the checklist of: Do I actually want to own a physical copy of this book? Â Do I need a physical copy? Â And finally, would I be embarrassed to have this sharing shelf space with the rest of my books (an important question, to be sure)? Â OK, the last bit is an exaggeration – but as I find myself acquiring ever more (academic, research-related) books, space is at a premium & my “light reading” is the first to get pushed out in favor of Serious Secondary Sources.

Looking over what I’ve read in the past few weeks, there’s nothing to be ashamed of, particularly – it’s just not “serious” (as in, having a direct relationship to my research or field of study). Â A lot of it is still historical & the vast majority is non-fiction – but I always find it interesting to compare with friends what we consider “fluff,” since it tends to vary wildly. Â I have just moved on from a six month sojourn with Tudor history (mostly pretty serious history books; but again, it’s not my field & I can just turn off and enjoy in a way I can’t when I read Chinese history books), where I read good stuff, bad stuff, and in between stuff (and still have a few volumes I need to finish off for good measure). Â I’ve been tending towards the slightly more eclectic of late, though still sticking to some favored genres. Â Anyways, a couple of highlights:

Two books on the Battle of the Little Bighorn (here is where e-books drive me crazy: what I really wanted was Evan S. Connell’s seminal – utterly wonderful – Son of the Morning Star, which of course was not available). Â First up was A Terrible Glory: Custer and the Little Bighorn – the Last Great Battle of the American West by James Donovan (2009), then Nathaniel Philbrick’s The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn (2010). Â I read these in quick succession, which was good for comparative purposes. Â The Little Bighorn, like the Civil War, has a terribly devoted fanbase and has basically been done to death – which isn’t to say there isn’t anything “new” to say, just that an awful lot of books seem to crib unabashedly off forerunners (you can feel Connell’s influence on both newer volumes – Son of the Morning Star has aged exquisitely). Â Still, it’s one of those subjects I like to come back to, as my mother likes to claim that a trip as a 4 year old to Crow Fair – including a sidetrip to march around the battlefield – was a formative event for me as a youngster. Â She’s possibly right; I do know that when I read accounts, I find myself wanting to go back (it’s on the list for next year or the year after, I hope). Â In any case, while neither book was particularly enlightening, they were solid introductions and reasonably researched popular histories (Philbrick was in desperate need of a better editor). Â I’m still hoping Connell’s magnificent narrative will show up in digital format sooner rather than later ….

I read two biographies, drawn from wildly different perspectives: Stacy Schiff’s Cleopatra: A Life (2010)Â and Lover of Unreason: Assia Wevill, Sylvia Plath’s Rival and Ted Hughes’ Doomed Love by Yehuda Korean & Eilat Negev (2008). Â Not simply divided by time & subject matter, the books were on opposite ends of the spectrum, quality-wise. Â Schiff’s take on Cleopatra was surprisingly good – considering the dearth of sources we have, and the fact that Schiff is not a classicist, really good. Â I came across it on the hunt for Robert Graves’ I, Claudius (also not available in digital format – sigh), and while it wasn’t exactly what I was hoping to sink into, it was a nice diversion for an afternoon. Â The author also spent a fair amount of time considering how history has come to be, at least insofar as it reflects on the telling of Cleopatra’s life. Â Parts of it felt like coming home & I’ve already downloaded a copy of Caesar’s De Bello Gallico to flit through for fun at a later date, since I’ve been feeling renewed interest in at least sort of returning to well-loved Latin tomes of yesteryear. Â I got the impression from Amazon many people were expecting a much “beachier” read – it wasn’t taxing, but I did find it quite satisfying and well written. Â It wasn’t mindless fluff to be wandered through without thinking, though I guess the cover image deceived a number of people.

The biography of Assia Wevill, on the other hand, was one of the less satisfying books I’ve read recently – actually, it was just plain bad. I imagine some of the difficulty came from the fact that no one in the story comes off as very likable – Wevill is constantly in odd triangular relationships with a husband and a lover, Plath is, well, Plath & prone to depression and rages, and Hughes comes off as an insensitive jerk, albeit a very talented one. Â But the authors didn’t seem clear on how they wanted to package Wevill – thus the narrative came off as confused, and red herrings were tossed into the text with little explanation (does a later feminist poet’s view that Hughes “murdered” Wevill really matter when thinking of what led to the event? Â Would it not be better to put that into the, say, section reflecting on her legacy or lack thereof?). Â It’s a bit unfortunate, because Wevill comes up only tangentially in biographies of Plath, or of Hughes, or of Plath & Hughes, so the promise of a biography centered on “the other woman” was intriguing. Â In the end, though, the only one I felt sorry for was the young daughter of Wevill & Hughes, Shura, who wound up dead on the floor of the kitchen alongside her mother.

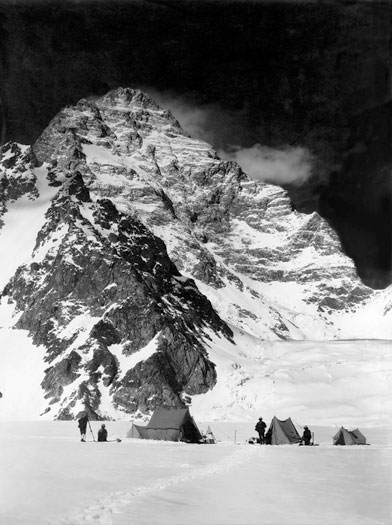

I read some other assorted things – a book on the Donner party, two books on Anabaptists in the US – which were consumed in much the same way I consume TV: they just sort of were. Â However, I’m currently trotting through a very fun history book that involves one of my very favorite genres of non-fiction – namely, high-altitude climbing tales. Â Now, I am not a climber. Â I will never be a climber; I will certainly never be a high-altitude climber. Â I’m not even sure when I developed a taste for climbing literature. I do remember being totally fascinated when they found George Mallory’s beautifully preserved body on Everest a few years back, and I read Jon Krakauer’s Into Thin Air a few years after it came out. Â Other than my inborn hillbilly love of mountains – and the Himalaya and other high ranges are certainly impressive ones – there’s really no rhyme or reason for my affection for non-fiction stories centered on climbing this or that crazily high point. Â Maybe it’s simply that it’s so out of the realm of possibility for my life – I can’t even fathom wanting to do something like climbing Everest or K2 – that it goes from non-fiction to high fantasy. Â There is something otherworldly about the high mountain scenes captured by talented photographers.

In any case, while I’ll usually read (guiltily, in the bath, ravenously)Â memoirs and accounts of varying quality as my most favored of fluff reading, Amazon – for once – had a good suggestion for me in Maurice Isserman & Stewart Weaver’s Fallen Giants: A History of Himalayan Mountaineering from the Age of Empire to the Age of Extremes (2010). Â It is possibly telling that my favorite book of the past few months was published by a university press. Â In any case, unlike most climbing literature which (at least these days) takes the form of memoir or disaster narrative, this is a delightful, juicy history that puts climbing in the Himalaya into context & situates it in larger forces. Â It’s really fun and really interesting – and quite a change from my usual guilty pleasure climbing reading. The authors have less interest in obsessively documenting the details of specific expeditions (probably wise, since a great many books exist with only the subject of this or that expedition); rather, they sketch the outlines of what happened while devoting the bulk of their efforts to detailing why this all matters in a bigger picture. Â I’m finding it engrossing, but good enough that I’m trying to spin out the reading experience as long as possible – thus only reading in chunks here or there. Â Luckily, it’s a pretty “weighty” tome (or would be, if I had a paper copy), so there’s plenty of pages left to be spun out.

I suspect it’s the sort of thing that would bore anyone looking for a quick, light, inspirational (or cautionary) tale to tears, but it’s the sort of “fluff” I love best: serious history that has no bearing on the stuff that I do. Â Or at least, if I don’t take notes, I don’t feel bad. Â Which doesn’t mean, of course, that I don’t read the footnotes! Â I’m looking forward to getting back to my realm of expertise, but a few weeks of diversion has been restful & good for me – I’m feeling more energized than ever to delve back into Meng Chengshun, Meng Chao, opera, and various other projects.

2 comments for “Recharging the batteries”